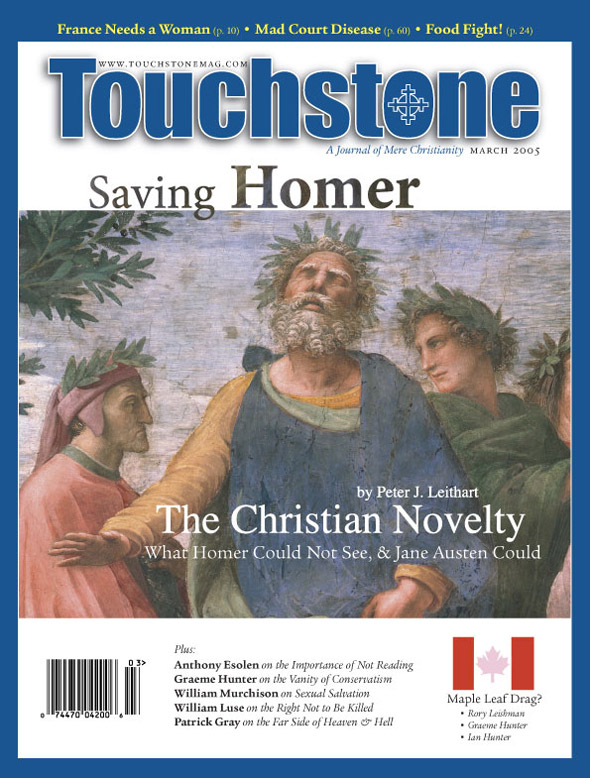

Feature

The Christian Novelty

What Homer Could Not See, & Jane Austen Could

Adam, Paul would have insisted, was as historical a person as you or I, and so was Jesus. Death entered a good world because Adam sinned, and new life entered the sinful world because Jesus obeyed and sent the Spirit. Adam’s sin was a historical event, and so was the resurrection of Jesus, and so was Pentecost.

These are the key points in human history, a history that includes Abraham, David, Solomon, Nebuchadnezzar, Cyrus the Persian, and Caesar Augustus, not to mention Augustine, Charlemagne, Napoleon, Saddam Hussein, Billy Graham, and Osama bin Laden. In Paul’s estimation, anyone who thought that the new life through Jesus pertained to some realm outside this history was simply an unbeliever. The gospel said otherwise.

Discerning this new life at work in the world is an act of faith, but if the gospel is true, if new life was unleashed in the world on Easter morning, it will leave footprints. And, as the church fathers were at pains to point out, it did. Athanasius noted all the pagans turning from their idols, all the warring tribes becoming brothers, all the swords being beaten into plowshares, and he used these things to expound the effects of the Incarnation.

One of the most evident illustrations of the effect of the gospel is found in the history of Western literature. That history is, to put it in Pauline terms, marked by a transition from the literature of death to the literature of life. Heroes of ancient epics are haunted by the fear of death, and recklessly pursue memorable deeds on the battlefield to secure some semblance of an afterlife. Eternal existence in the songs of poets is, after all, better than no after life at all.

The early Christian heroes, by contrast, were utterly fearless of death, not least the martyr’s death by torture. They went to their deaths gladly because they knew something the pagan world did not know: that the world was, despite appearances, a deeply comic place.

Tragedy to Comedy

A tragic story ends badly for the major characters. Hamlet is dead at the end of his play, and so are Macbeth, Lear, and Othello at the end of theirs. Comic stories end happily for the main characters. Fairy tales are comic: The boy rescues the girl, they marry, they live happily ever after. At the end of a tragedy, everyone is dead. At the end of a comedy, everyone is married.

Ancient literature is marked as the literature of death particularly in its bias toward tragedy. Greeks wrote comedies, of course, but their genius was for tragedy. William Butler Yeats was not your average orthodox Christian, but he recognized that a threshold had been crossed with the coming of Christianity. Classical culture, he wrote, was essentially a heroic culture, aristocratic and violent, its central myth the story of Oedipus, who kills his father and lives in incest with his mother. It was succeeded by Christian culture, which is democratic and altruistic, based on the myth of Christ, who appeases and reconciles his father, crowns his virginal mother, and rescues his bride the Church. . . . Tragedy is at the heart of Classical civilization, comedy at the heart of the Christian one.

Even when the ancients wrote comedies, moreover, their hearts did not seem to be in it.

W. H. Auden once commented that a Christian society could produce comedy of “much greater breadth and depth” than could a classical society. Its comedy was greater in breadth because classical comedy is based on a division of mankind into two classes, those who have arete [heroic virtue] and those who do not, and only the second class, the fools, shameless rascals, slaves, are fit subjects for comedy. But Christian comedy is based upon the belief that all men are sinners; no one, therefore, whatever his rank or talents, can claim immunity from the comic exposure and, indeed, the more virtuous, in the Greek sense, a man is, the more he realizes that he deserves to be exposed.

Peter J. Leithart is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church in America and the president of Trinity House Institute for Biblical, Liturgical & Cultural Studies in Birmingham, Alabama. His many books include Defending Constantine (InterVarsity), Between Babel and Beast (Cascade), and, most recently, Gratitude: An Intellectual History (Baylor University Press). His weblog can be found at www.leithart.com. He is a contributing editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor