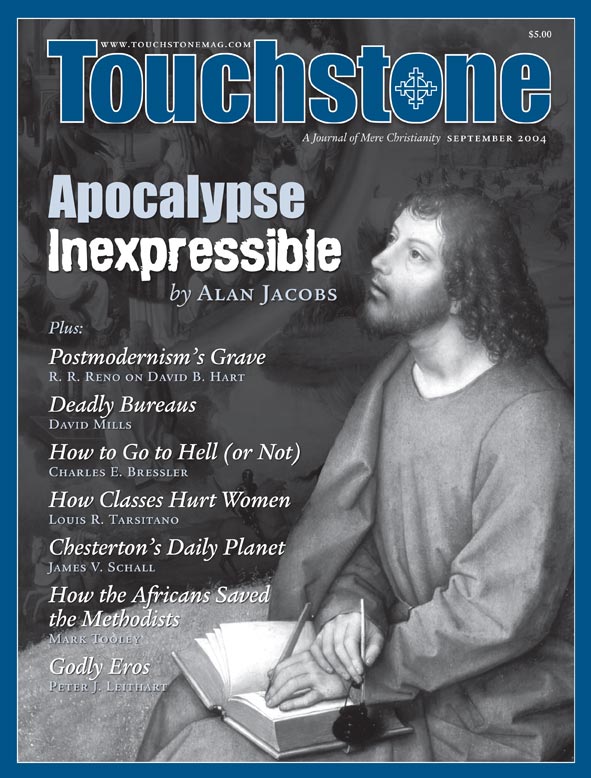

Feature

The Inexpressible Apocalypse

Maybe St. John Did, After All, Write the Final Word

I begin with a cartoon by the great Roz Chast that appeared in The New Yorker some years ago. It bears a headline: “The Four Press Agents of the Apocalypse.” I can no longer remember what the first three press agents say, but the words of the fourth I recall perfectly: “It’s a-comin’, and it’s gonna be big.”

We Puff or Sneer

It is always painful, I know, to be forced to endure the unpacking of a joke, but please bear with me: this one, I think, is worth unpacking. The idea behind the joke, of course, is that press agents devote their lives to making small things seem big, to blowing things up—“puffing,” as the ad-world jargon has it.

“Puff Graham,” the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst commanded his subordinates half-a-century ago, once he saw the charisma of the ambitious young evangelist—little imagining that long after people had forgotten Mr. Hearst (save, perhaps, as the model for Orson Welles’s Charles Foster Kane), Billy Graham would still be famous. Sometimes what the press agents puff can inflate beyond all expectation, and sometimes, believe it or not, there arise persons or events vaster than our powers of inflation, denigration, or praise.

Some years ago John Updike wrote, “We cannot imagine a Second Coming that would not be cut down to size by the televised evening news, or a Last Judgment not subject to pages of holier-than-Thou second-guessing in The New York Review of Books.” I must admit that when I reflect on the Last Judgment, I never wonder what the New York Review of Books would think about it. Presumably they would commission Garry Wills to write a long essay demonstrating how God had, through a combination of administrative mismanagement and mendacity, bungled the whole affair, which in any case should have been left to an ad hoc bipartisan task force overseen by a major activist/intellectual—Hillary Clinton, say.

In any event, if the cartoon mocks our inability to imagine events larger than our powers of puffery, Updike suggests our inability to imagine events beyond our powers of sneering diminution. For Updike, this deficiency of imagination stems from a governing fact of contemporary cultural life: “Our brains,” he writes, “are no longer conditioned by reverence and awe.” One might extend that remark by saying that our brains are conditioned by irreverence and a resistance to awe.

But there is a more fundamental point to be made than either Chast or Updike indicates: It is, simply, that the Apocalypse cannot be narrated. Apocalypse in the true sense is the end of history, and the end of history is the end of narrative; it is beyond our powers of storytelling because it is beyond story itself. Having said this, I may well have made the only point I am capable of making on this subject. But that is a question that I will return to near the end.

The validity of my claim that the Apocalypse cannot be narrated may only be tested once we are sure what we mean by “apocalypse.” It seems to me that, when that term is employed in literary discourse, it is used in two different ways, with different degrees of legitimacy and usefulness. It is used both for stories that depict the end of the world (these are usually secular) and for those (usually Christian) that depict the events leading to the Last Trump. The second will be our main subject.

The End of the World

First, we have depictions (usually uninformed by Christian belief) of the “end of the world,” by which is usually meant either the end of humanity or the end of life on this planet. Thus Neville Shute’s On the Beach or Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, to take a couple of famous examples. Narrative fiction is the typical, though not the exclusive, venue for such stories. (It is interesting to note that this kind of book is a staple of high-school reading lists.)

Alan Jacobs is Professor of English at Wheaton College in Illinois. His books include A Theology of Reading (Westview Press), A Visit to Vanity Fair and Other Moral Essays (Brazos Press), and Shaming the Devil: Essays in Truthtelling (Eerdmans).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor