Romancing the Past

A Critical Look at Matthew Fox & the Medieval “Creation Mystics”

by Barbara Newman

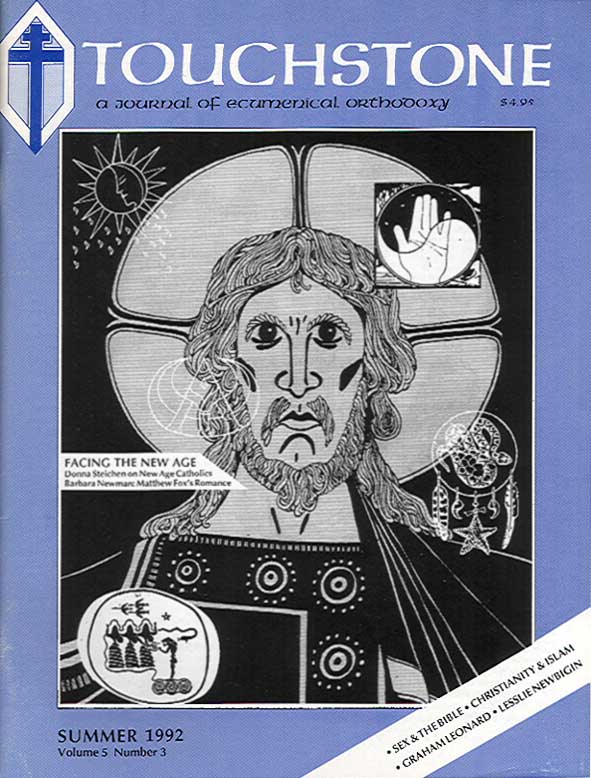

It is no exaggeration to say that Father Matthew Fox is one of the best-loved Catholic theologians in the United States. The Dominican priest had achieved celebrity through his many books, his lecture tours, and his Institute in Culture and Creation Spirituality, based in California, long before the Vatican set the seal on his prophetic career by silencing him for a year. Fox was thus honored with the same accolade once received by such theological giants as Yves Congar and Teilhard de Chardin. Unlike those thinkers, however, Fox has taken a playful and even whimsical approach to theology, as suggested by the titles of his early books: Whee! We, wee All the Way Home: A Guide to the New Sensual Spirituality (1976) and On Becoming a Musical, Mystical Bear: Spirituality American Style (1972).

The ursine mystic was immortalized in the imprint of Bear & Company, a press that Fox cofounded in 1981. For the past decade Bear & Company has promoted Fox’s brand of creation spirituality by publishing his own works, primers of the New Cosmology, and the popular “Meditations with” series, including meditations with Meister Eckhart, Julian of Norwich, Mechtild of Magdeburg, Dante, Thomas Aquinas, Native Americans, and animals. These slender volumes, featuring free adaptations of their sources arranged for daily prayer, enable the adherents of Fox’s “spirituality American style” to perceive a deep continuity between themselves and the medieval Christian past. But since much of this continuity is a fiction constructed by Bear & Company’s practice of selective editing and dubious translation, the press’s successful promotion of these texts creates a problem for anyone concerned with historical as well as spiritual truth-in-packaging.

The questions raised by Fox’s enterprise are large and intractable ones: Does the theologian have a responsibility to the past as well as the present? What is the place of historical theology in contemporary religious thought? Can we create a usable past for ourselves and, at the same time, remain or become historically honest? Is there a timeless core of Christian truth that can and should be stripped of its antiquated garb to be made forever new? What, in fact, is Holy Tradition and how should we use it? I have chosen Matthew Fox as a case study because his work poses the problem in acute form, but any theologian who grapples seriously with tradition must face the same issues. I have chosen his work on St. Hildegard because she has been the focus of my own scholarly efforts, as well as the centerpiece of Fox’s attempt to rewrite Christian history.

Taking pride of place in his list of “creation-centered mystics,” Hildegard is featured not only in a a “Meditations” volume1 but also in Fox’s Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen (1985) and in a series of translations published by Bear & Company. Little-known in the Anglophone world before 1980, Hildegard was a twelfth-century German prophet and visionary. A Benedictine abbess and founder, she was also a monastic reformer, preacher, composer and liturgist, medical writer, and prolific theologian who was and still is venerated as a saint in her homeland, although she narrowly missed canonization.2 In the mid-1970s, when I was a graduate student hunting for a suitably arcane dissertation topic in medieval studies, I came upon St. Hildegard almost by chance and fell under her spell at once. At that time few scholars in America had ever heard of Hildegard and fewer still had read her. But a decade later, when my book finally appeared,3 it had a ready-made public at hand. I discovered that my author, recently so obscure, now had fans in every quarter thanks to the efforts of Bear & Company. Whenever Hildegard’s name came up for discussion, I was inevitably asked what I thought of Matthew Fox. From a selfish point of view, of course, I had reason to be grateful to him. Yet the more I read of his work on medieval mysticism, the more ambivalent I became.

On the one hand, there is much to admire in Fox’s theological project. On the other, much of what he says about Hildegard, and every other historical figure he cites, turns out to be dead wrong—factually careless, anachronistic, and tendentious. Numerous quotations are drawn not from her original Latin texts but from Bear & Company’s Meditations—edifying snippets taken out of context, translated secondhand from the German, bowdlerized to remove offending language, and paraphrased in a relentlessly banal and simplistic style. Not surprisingly, Hildegard subjected to this treatment sounds much like Meister Eckhart, just as Thomas Aquinas sounds like Matthew Fox and Dante like a Hallmark card. Having remastered these ancient voices in a contemporary mode, Fox then proceeds to celebrate them as exemplars of a “creation-centered tradition” culminating in his own theological synthesis, which is most fully and eloquently set forth in his recent book, The Coming of the Cosmic Christ (1988).

In order to appreciate the value Fox assigns to medieval mystics, it is necessary to understand his larger theological program. This program is radical and ambitious, and it is advanced with a passionate urgency inspired by the planetary crisis we now face. What Fox seeks is nothing more nor less than a “paradigm shift” in theology-from a fall/redemption to a creation-centered spirituality, from original sin to original blessing, from world-denying asceticism to life-affirming mysticism, from patriarchy to feminism, from repression to celebration of the body, from an anthropocentric focus on the self to an ecological focus on the cosmos. Fox’s Christology is predictably broad. Although he retains an interest in the historical Jesus (whom he interprets as a creation-centered mystic, crucified for his frontal assault on patriarchy), his real quest is directed toward the cosmic Christ, whom he sees incarnate in the universe as a whole. In The Coming of the Cosmic Christ, Fox goes so far as to identify Jesus crucified with Mother Earth, “dying at the hands of a patriarchal civilization gone mad with its attraction to matricide.”4

To save the planet and the human race, he proposes what is in effect a new religion that will unite the powerful energies of art, science, and mysticism—Fox’s “holy trinity”—in the service of wisdom and justice, compassion and celebration. This religion is not unlike that proposed by many spiritual teachers in the New Age movement; one can find similar prophetic and mystical teachings under the aegis of Hinduism, Sufism, Wicca, and a variety of other rubrics. Indeed, Fox practices what he calls “deep ecumenism,” noting that in parts of the world today, the religious lines of demarcation no longer separate Catholics from Protestants or even Christians from non-Christians so much as they divide progressives from conservatives within all traditions. Consequently Fox feels closer in spirit to a native American shaman, a feminist witch, or a Sufi master than he does to a repressive cardinal or an Opus Dei bishop.5

Fox’s theology in fact bears little resemblance to any historic form of Christianity. Although he finds much to admire in the Bible, he has drawn far more from other sources, and Jesus is no more central to Fox’s religion than he is to Islam. Yet Fox is a Dominican priest and his audience consists largely of disaffected Catholics, including a great many clergy and religious. For this reason, he must legitimate creation-centered spirituality for Christians by grounding it, so far as possible, within his own reading of the Christian tradition. Like most theologians, Fox has his own version of Church history with his personal heroes and villains. Two of the prime villains are St. Augustine and Isaac Newton, who inaugurated earlier paradigm shifts—Augustine turning from the cosmic Christ of the Greek Fathers to the “personal Savior” of his own guilt-obsessed psyche, and Newton from a mystical cosmology to a soulless world-machine. Fox’s heroes are the so-called creation mystics of the Middle Ages—Hildegard, Eckhart, and the rest. In order to cast them in this role, however, he is compelled to suppress or distort much of their actual teaching. His representation of Hildegard is a prime case in point.

Bear & Company’s translation of this Scivias, the first volume of Hildegard’s theological trilogy, is abridged to about half its original length. The omitted sections are those which the editor deemed “irrelevant or difficult to comprehend today.”6 Among these are lengthy passages promoting orthodox sexual ethics, commending virginity, expounding the theology of baptism and Eucharist, condemning heresy, upholding priestly ordination and celibacy, defending the feudal privilege of nobles, and exhorting the obedience of subjects. In other words, Hildegard is welcome to Fox’s mystical pantheon so long as she refrains from being a twelfth-century Catholic. Her holistic cosmology is acceptable, but not her defense of social and ecclesiastical hierarchies. Fox is delighted to stress her “womanly wisdom” but ignores the fact that she was a consecrated virgin, blithely ascribing to her his own ideas about “the recovery of Eros.” Since he also wants to make her a feminist, he rigorously edits her trinitarian thought to fit the standards of an inclusive-language lectionary. The divine Mother, who figures prominently in Hildegard’s visions, is allowed to remain; but the Father and his Son are ushered firmly out the door. Fox does not overtly criticize these unpalatable aspects of Hildegard’s thought; he simply ignores them.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor