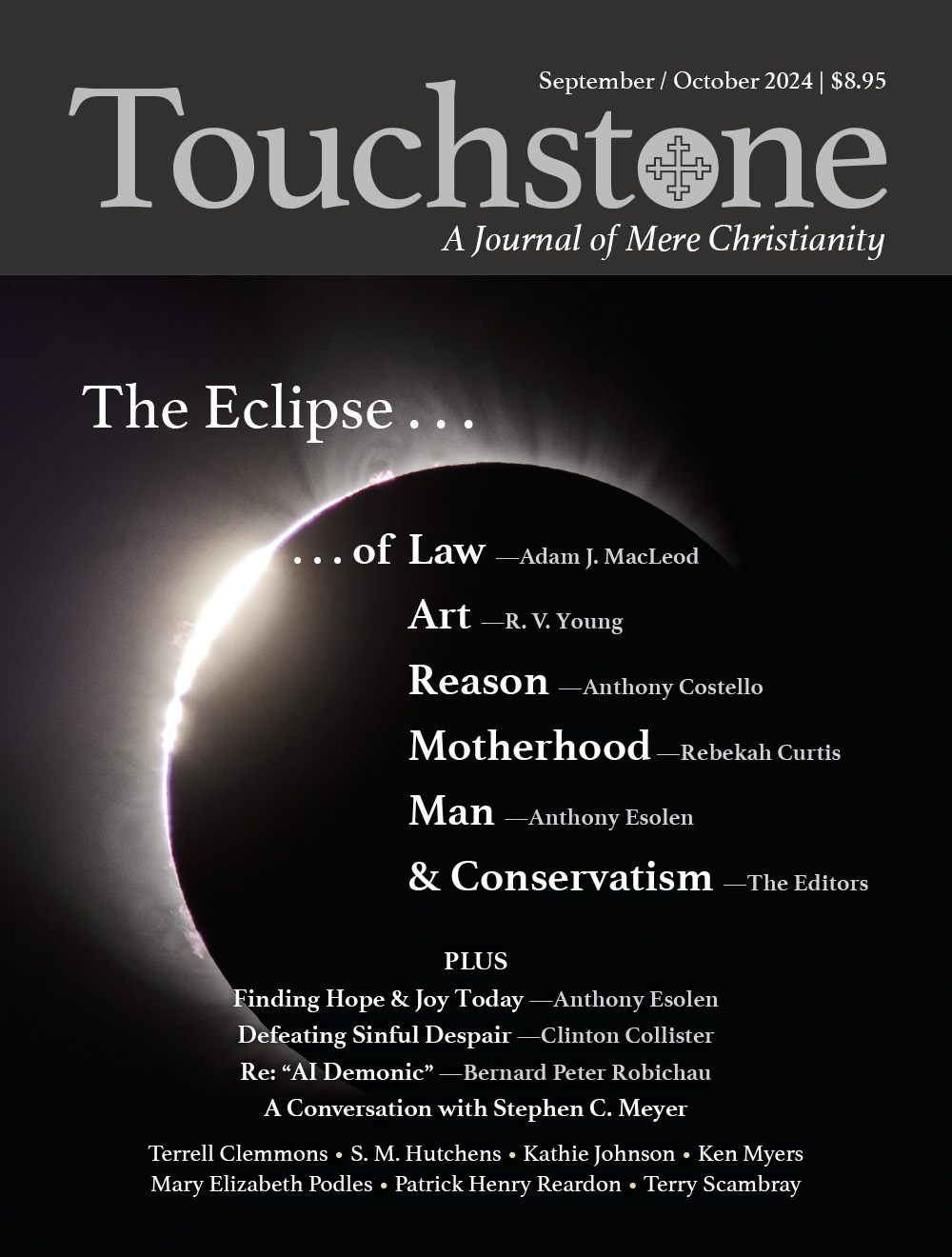

How Law Lost Its Way

An Abandoned Ruling Principle & How to Get It Back

by Adam J. MacLeod

In principle, the rule of law depends upon our acceptance of one basic truth about law. However, a century ago, our legal educators rejected this basic truth, and we have now lost the rule of law in principle. I want to talk about how we gained the rule of law and how we lost it—and how to get it back.

The rule of law, one of the great achievements of Christendom, was made possible by a simple idea. Non-lawyer Americans are accustomed to taking this idea for granted, but it was radical and even unlikely when first articulated 1,400 years ago. Indeed, that lawyers are losing hold of this idea today, at the very moment when human knowledge is vast and accessible to most of the world, proves just how fragile and contingent the rule of law is in the course of human history.

The basic idea on which the rule of law is constructed, and without which it cannot be sustained, is that law is essentially something independent of mere power. Law is neither the will of the sovereign nor the threat of sanction. It is not economic coercion, or cultural coercion, or gendered coercion, or religious coercion. Power may be necessary to make the law work in marginal cases, where practical reason breaks down and lawlessness threatens to prevail. But power is a tool of the law, not its source or essence. The essence of law is not found in violence or coercion. The essence of law is located within our capacities to understand, deliberate about, and communicate practical truths about what is just and therefore right to do.

Legal Essentials

In its essence, law is a reason for our actions. Law acts not primarily within our passions, fears, and appetites but rather within our minds. Law motivates us as rational creatures, creatures who bear the image of God. Bears and wolves do not negotiate contracts or filibuster legislation. Codfish and lobsters do not argue about who bears the burden of proving fraud or defamation. No non-humans make and obey law, and all human beings have the capacity to make and obey law.

This means that law is not the exclusive prerogative of the guy with the biggest biceps or largest pile of gold. The true sense of human equality is that we are all equal participants in, and subjects of, the law. No person is above the reach of the law’s governance, and no person is beneath the reach of its reasoned justifications. No one may flout the law; no one may make the law whatever he wants. And everyone deserves an explanation for the law. We must be prepared to explain why our laws and judgments are valid and thus command obedience.

This is the basic idea of Western jurisprudence. It is the foundation of the rule of law. And because it made possible the rule of law, this idea made possible civic trust; investment, creativity, and risk-taking; free trade and commerce; trusts, corporations, and charities; education and the arts; and all the other fruits of civilization.

This idea leaves ample room for jurisprudential pluralism. Law can be many things as long as it is not merely might making right. The just must make right. And the right must be just, whether it is settled as a matter of natural justice or legal justice. Indeed, not all law must come from the same source. Some laws may be strictly necessary as a matter of natural reason, like the duties of parents toward their natural children and the inalienable right to life. Other laws are conventional, like the customary rights of trial by jury and freedom of the press. The crucial proposition to maintain is that law is not whatever the most powerful people say it is.

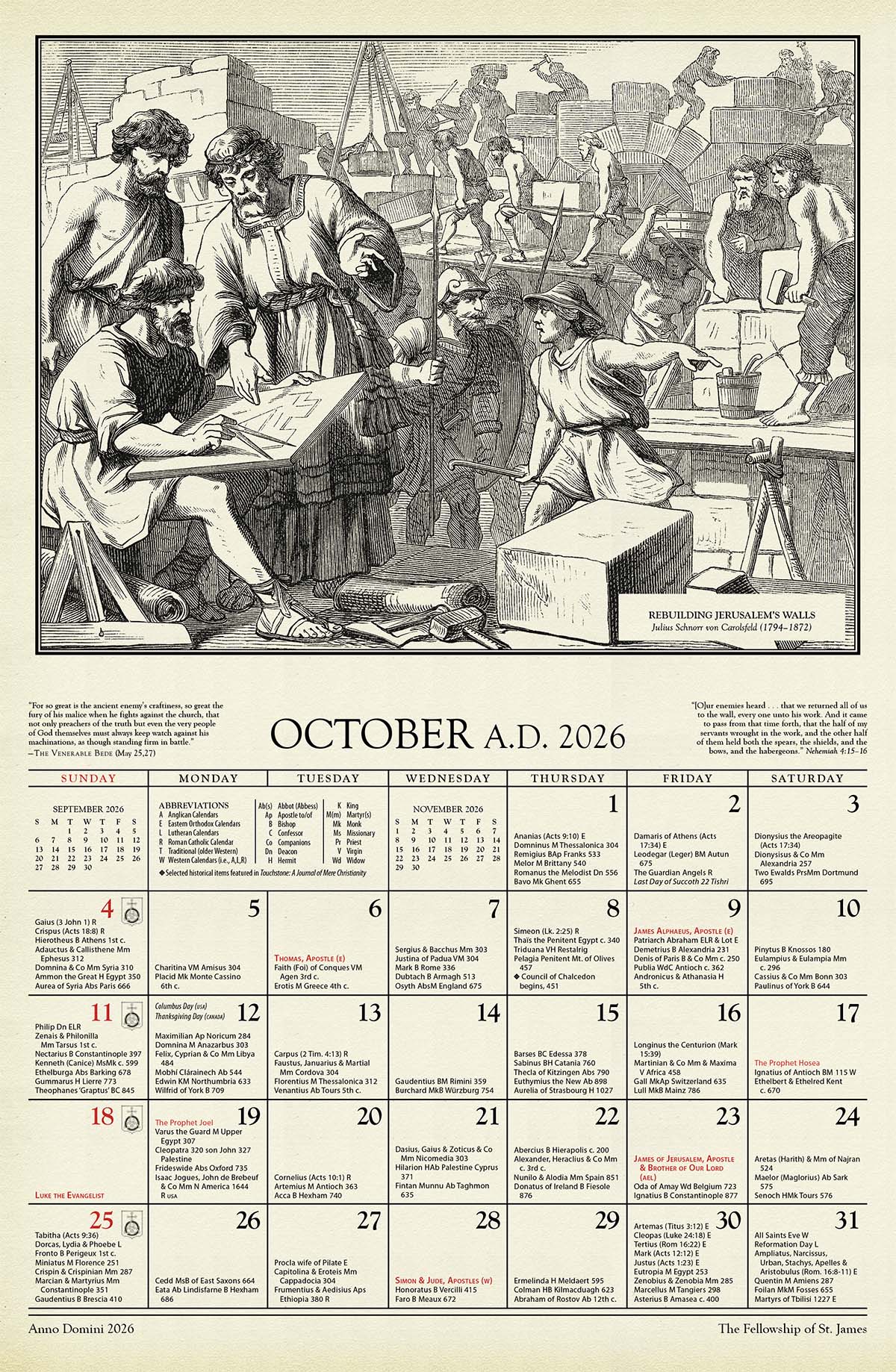

Justinian’s Genius

The patron of this idea, and therefore the grandfather of the rule of law, was the emperor Justinian (482–565). His Corpus Iuris Civilis (consisting of four parts: the Code, the Digest, the Institutes, and the Novels) synthesized Roman law, natural law, and the ius gentium, the law that is common to all civilized nations. Justinian’s jurists first described in detail the rights and institutions of Western law as creations of the human mind and artifacts of human making. The laws we have arelaws not merely because the senate or emperor said so but because they are the means that persons have devised to enable us to achieve justice, to do what is right with respect to other persons. They accord with practical reason. They are intelligible, logical, and rationally related to valuable human ends. And they are made things, discernable objects of human knowledge. They exist independently of sovereign will. We can study them, learn them, obey them, and hold others accountable to them.

Justinian’s jurists had on hand a compelling and vivid illustration of the separateness, priority, intelligibility, and enduring nature of law: the Twelve Tables. After the early Romans abolished the monarchy, they briefly wallowed about in chaos and ruled by “mere custom” before they appointed ten men to exercise the authority of the state to put their laws in writing on ivory tablets and to display those tablets, which were twelve in number, for public view. Thereafter, those who would rule or render judgment were obligated not to exercise their own discretion but instead to act in obedience to a “correct interpretation” of the laws. They were obligated to reason together and to connect their judgments rationally to legal texts, so that all could consider whether they were exercising legal judgment or mere power.

By placing the Twelve Tables above those whose job it was to interpret and declare their meaning, the early Romans placed power under the law. Power is under law insofar as it is governed by reason and word, and the reasoning of those entrusted with the law is open for all to examine. There legal power must remain for a people that is governed by law rather than by physical might or wealth.

Adam MacLeod is Professor of Law at St. Mary’s University and a Senior Research Fellow of the Center for Religion, Culture and Democracy.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Law from the online archives

37.5—Sept/Oct 2024

Why Law Schools Can't Teach Law

A sidebar to How Law Lost Its Way by Adam MacLeod

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor