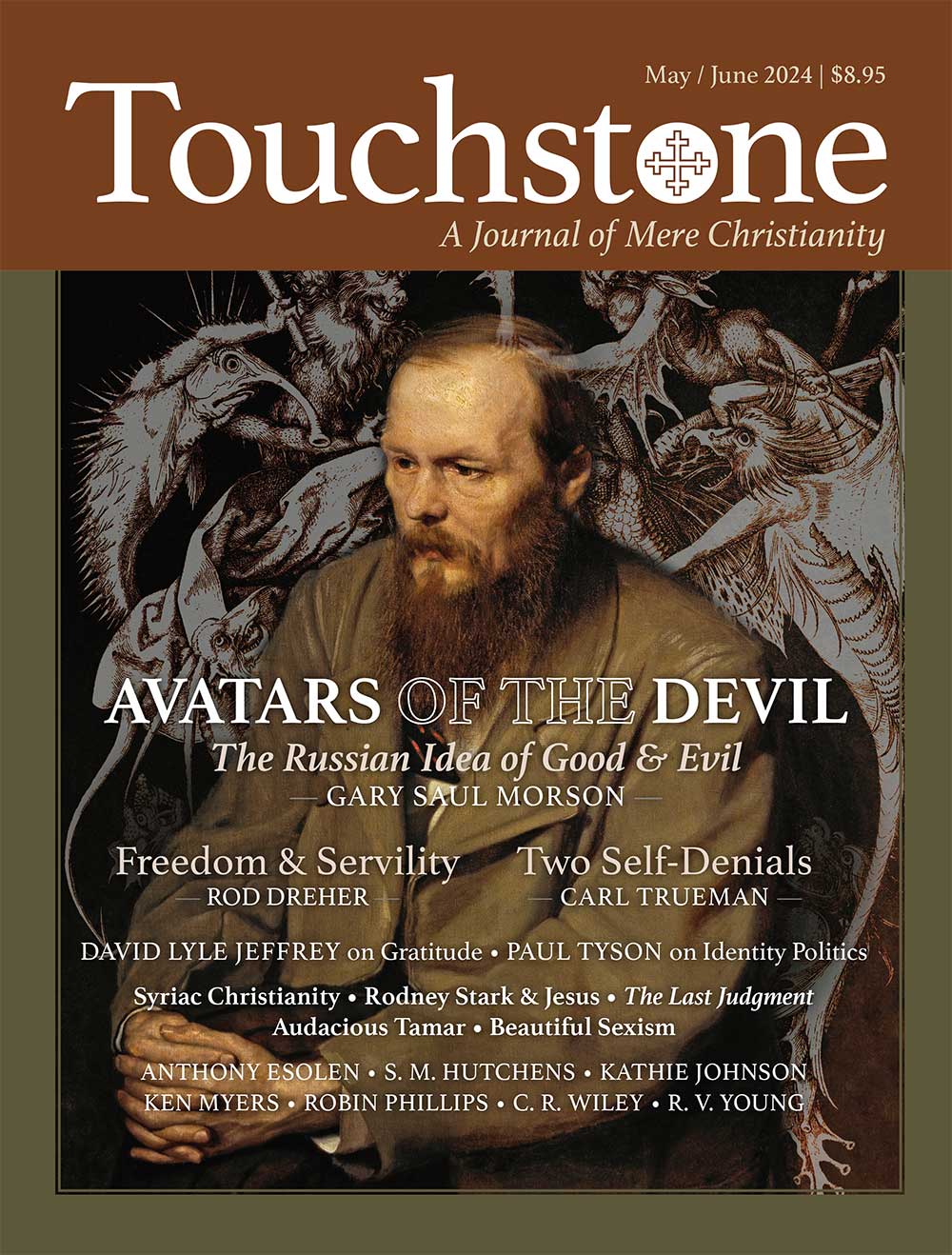

Avatars of the Devil

The Russian Idea of Good & Evil

The devil is in the details, and so is the angel.

Russian history exhibits two contrary visions of human life, the dramatic and the prosaic. One led to the cult of revolution, the other to the realist novel. Russia’s greatest writers, from Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Chekhov on, appreciated the quotidian and stressed ordinary virtues. To understand good and evil, they taught, one should look within and pay attention to the people always before one’s eyes. The meaning of life is not mysterious but familiar; it is not concealed in the mists of distance but hidden in plain view.

Russian history is nothing if not dramatic. If English history is a story of gradual reform, Russia alternated between sudden, violent upheaval and utter stagnation. As Russians never tired of pointing out, Peter the Great Westernized the country almost overnight. “Peter had no time to waste,” observed “furious” Vissarion Belinsky, Russia’s most influential critic. “He could not sow and wait calmly until the scattered seed would germinate. . . . He understood . . . that sweeping changes . . . that [elsewhere] have been the work of centuries” had to be accomplished suddenly. The only way to do so was to apply unprecedented brute force.

The Bolsheviks out-Petered Peter. The Book of Revelation promises to “make all things new,” and the militantly atheist Bolsheviks believed they could do so on their own, without divine intervention. Engels called it “the leap from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom.” No longer would humanity be subject to the relentless laws of nature; those laws would now be reformulated according to human will. Listen to Trotsky: “The present distribution of mountains and rivers, of fields, of meadows, of steppes, of forests, and of seashores, cannot be considered final. . . . . Faith merely promises to move mountains” but “man in Socialist society will command nature in its entirety, with its grouse and sturgeons.”

Bolsheviks were obsessed with the idea that sheer will, directed by the Party, would command forces previously beyond human control. In Bolshevik terms, “spontaneity” would yield to “consciousness.” The “chaos of the market” would be superseded by the planned economy, which, because nothing would just happen, would eliminate waste and therefore be exponentially more productive. The same thinking applied everywhere: “Communist life will not be formed blindly, like coral islands,” Trotsky instructed, “but will be built consciously. Life will cease to be elemental” and even “breathing, the circulation of the blood, digestion, reproduction” will all bend “to the control of human will.” “Ye shall be as gods,” Satan promises Eve, and Trotsky foresaw a race of supermen: “The average human type will rise to the heights of an Aristotle, a Goethe, or a Marx. And above this ridge new peaks will rise.” Stalin concurred: “Our task is not to study economics but to change it,” he proclaimed. “We are bound by no laws. There are no fortresses which Bolsheviks cannot storm.”

This revolution, in short, was unlike all previous ones because it transformed the nature of the universe. Perhaps the most striking formulation of this idea belongs to Yuri Piatakov, whom Lenin called one of the six most promising Communists. When in 1928 his old friend Nikolay Volsky reproached him for having renounced his former Trotskyite views, Piatakov ascribed his conversion to his belief that the Party could literally achieve miracles:

According to Lenin, the Communist Party is based on the principle of coercion which doesn’t recognize any limitations. . . . . And the central idea of this principle of boundless coercion is not coercion itself but the absence of any limitation whatsoever—moral, political, and even physical. . . . . Such a Party is capable of achieving miracles. . . .

A real Communist . . . . that is, a man who was raised in the Party and had absorbed its spirit deeply [would] become . . . . a miracle man.

As novelist Vasily Grossman observed, “the violence of the totalitarian state . . . . becomes an object of mystical worship.”

In Love with Terror

Nadezhda Mandelstam recalled how even intellectuals who should have known better succumbed to the mystique of revolution:

Gary Saul Morson is Lawrence B. Dumas Professor of the Arts and Humanities and Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Northwestern University.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on literature from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

Support Touchstone

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor