Instruments of Grace

Flannery O’Connor & the Pantocrator

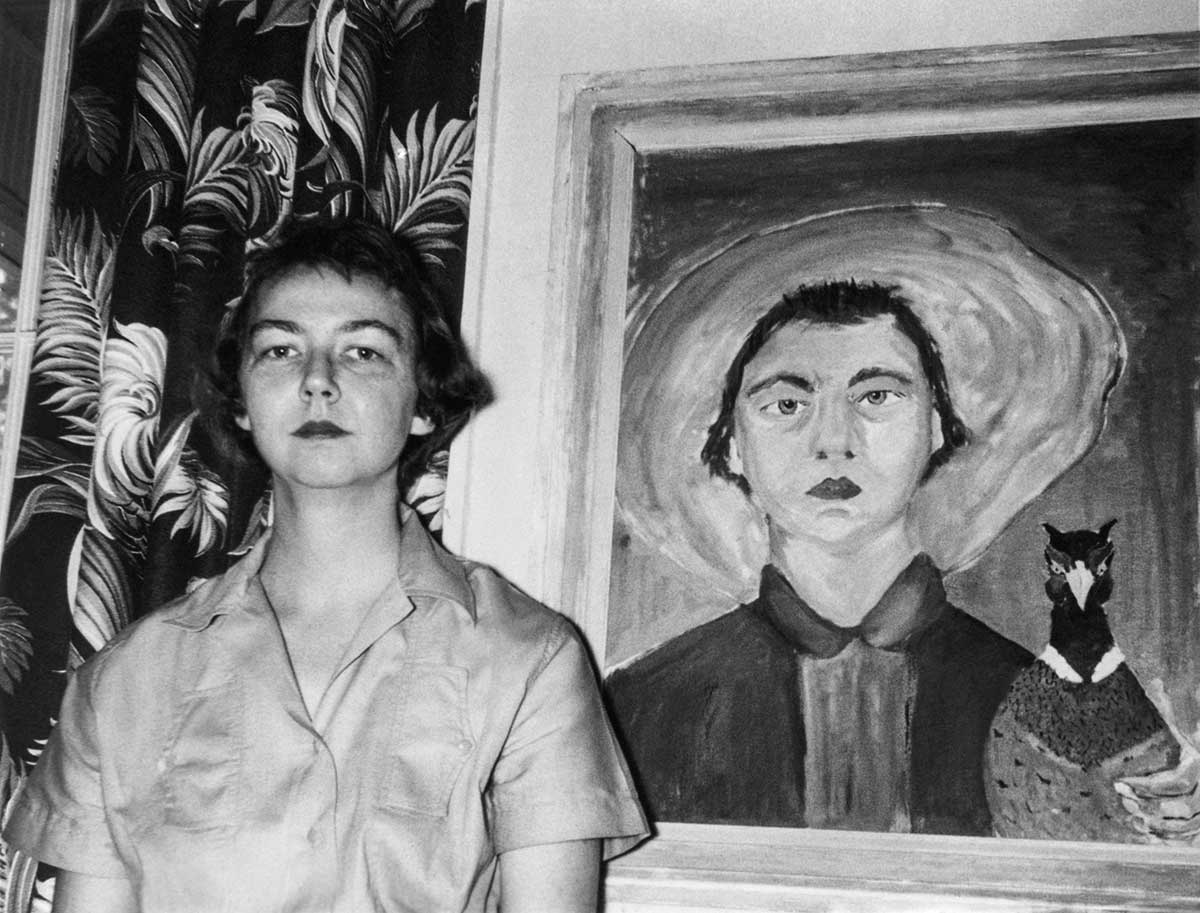

Flannery O’Connor had more than a passing interest in the icon of Christ Pantocrator that looks down from the central dome of Orthodox churches, signifying that he and no other is the Ruler of all things. She made it the basis of her celebrated self-portrait, albeit in complex fashion. And in “Parker’s Back” she put it to powerful fictional use. This is not only her last finished story before her death at age 39 in 1964 but one of her funniest as well.

Obadiah Elihue Parker has covered his body with tattoos of sexual power and predation: “a tiger and a panther on each shoulder, a cobra coiled about a torch on his chest.” Thus does he fashion himself as a tattooed conqueror of women: “He had never yet met a woman who was not attracted to them.” Not, that is, until he meets Bible-quoting, image-despising Sarah Ruth, a fundamentalist who has nothing but contempt for them: “It’s a heap of vanity,” she snorts, “Vanity of vanities.” And when Parker seeks to demonstrate that he is no sort of a Christian by flinging forth a string of curses, she silences him by whacking him mercilessly with a broom.

The God whom Sarah Ruth has encased in her gnostic box is the same God whom O. E. Parker has spent his life seeking to escape. He hilariously fails to flee the Hound of Heaven when he crashes his tractor into the single and easily avoidable tree standing at the center of the field he is mowing. The collision sets the tree ablaze and throws Parker shoeless to the ground, Moses-like. That the God-fleeing Parker finally finds God in a cow pasture strikes the reader as funny, of course, but Parker is far from cheered. He hardly pauses before heading straight for a tattoo parlor.

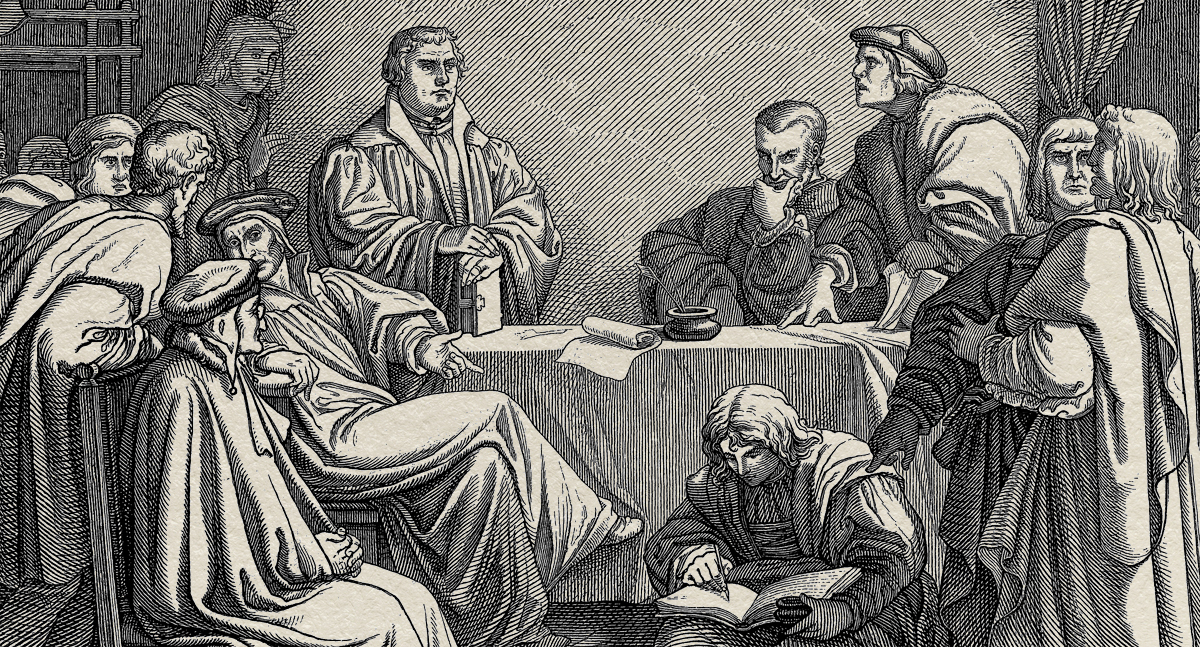

O’Connor again amuses her readers by having Parker locate this most solemn of Christian images—Christ Pantocrator—among the most saccharine pictures in the tattooist’s catalogue: “The Good Shepherd, Forbid Them Not, The Smiling Jesus, Jesus the Physicians’ Friend.” As he ponders them, Parker hears a voice commanding him to “GO BACK.” And so he returns to the singular image he cannot ignore: “the haloed head of a flat stern Byzantine Christ with all-demanding eyes.” Painfully but patiently Parker has his back—the only portion of his body he cannot vaingloriously behold—incised with a figure of the Lord whom he has unforgettably met. At last, Parker believes, he has found the image that will satisfy his hyper-Christian wife.

Far from it. In a scene at once comic and sad, Sarah Ruth greets Parker’s return with contempt for his new tattoo. When Parker demands that she look at the Pantocrator, whose bearer he has now permanently become, she confesses (far more truly than she understands), “It ain’t anybody I know.” “God don’t look like that,” she adds. “He’s a spirit. No man shall see his face.” The hard-eyed Sarah Ruth thus drives Parker out of their house by thrashing him again with a broom, knocking him senseless and raising large welts on the face of the tattooed Christ. Thus is the story brought full circle back to its beginning, as Christ is crucified afresh and a believer is made to take up his own cross, as it shall be until the end of time.

An Opposite Beauty

Flannery O’Connor would have known little if anything about the venerable icon tradition that stretches back to the early Christian centuries. Nor is there any indication that she would have shared the estimate of icons that I attempt to describe. Even so, we need to set her use of the Mt. Sinai Pantocrator in the context of the inexhaustibly rich canons and practices of icon-making, even if she knew nothing of them.

In teaching and lecturing on the icon tradition, these are the essential truths about it that I have gathered from numerous sources. “Beauty will save the world,” declares the narrator in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. This is no Keatsian claim that “‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,’—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” It is, instead, an Orthodox theological claim rooted in icons. In that same novel, we also hear it said that “there is only one face in the whole world which is absolutely beautiful” and that “the Incarnation [is] the epiphany of the Beautiful One.”

Icons thus seek to portray the beauty of God in Jesus Christ and his saints. What the gospel proclaims to us by words, declared the Council of Constantinople (869–870), the icon proclaims and renders present for us by color. Icons are built, therefore, on a theology of spiritual presence rather than natural representation. They are not images we behold in order to discern an earthly rendering of the Holy. Rather does God’s own splendor radiate through them, filling those who rightly venerate them with life-transforming Reality. Thus do icons behold us.

They are not an expression of the artists’ subjective perspective on the world, an attempt to portray or reflect the visible universe as they see it. Icons are the product of a long Tradition that has little to do with artists’ own genius or ideas, their intuitions or emotions, their creativity or imagination—although they are free to make small variations on the chief iconic themes, events, persons, and so forth. Icons are based on carefully proportioned geometric lines, on symbolic gestures, on fixed color correspondences—all of which have been elaborately laid down over centuries of practice. These sacred canons serve as guides and safeguards to guarantee both spiritual continuity and doctrinal unity. As the Council of Nicaea decreed in 787: “Only the technical aspect of the work depends on the [iconographer]; its design, its disposition, its composition depend quite clearly on the Holy Fathers [i.e., the theologians and bishops of the church].”

Ralph C. Wood was, until his retirement, University Professor of Theology and Literature at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. His books include The Comedy of Redemption (University of Notre Dame Press), Flannery O’Connor and the Christ-Haunted South (Eerdmans), and Chesterton: The Nightmare Goodness of God (Baylor University Press).

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on imagination from the online archives

11.5—September/October 1998

Speaking the Truths Only the Imagination May Grasp

An Essay on Myth & 'Real Life' by Stratford Caldecott

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor