Does God Have a Body?

on Divine Embodiment in Christ & Creation

Does God have a body? The very idea may seem preposterous: God is not an animal, whether rational or irrational. The higher up we move on the chain of being, the more ethereal its occupants. Even if, as some maintain, angels, too, have bodies, it would still seem axiomatic to say that God does not. He is spiritual, infinite, and invisible—perfections that appear at odds with an embodied God. The problematic implications of divine embodiment seem obvious: it either makes God human (anthropomorphism), or it confuses him with the cosmos (pantheism).

When St. Augustine asks whether we can see God with bodily eyes, he is at pains to reject the error of the anthropomorphites: “There are some who presume that God is nothing but a body, supposing that whatever is not a body is not a substance at all. I think that we must oppose them in every way” (Ep. 147). Ascribing embodiment to God would seem to drag him down to the human level. Or, at best, it would place him alongside the Greco-Roman gods: Zeus had a body, but his sexual escapades make clear that it was the source of endless trouble. We may well end up anthropomorphizing and mythologizing the Christian faith by ascribing a body to God.

The Christian God may not have a body the way that Zeus had a body, but could the entire cosmos be the body of God? Such a claim, too, would seem intolerable: does it not veer dangerously close to confusing Creator and creature? Pantheism (equating God and universe) has always been considered incompatible with the Christian faith, for it destroys the transcendence of God and ends up justifying whatever exists—whether good or evil—as divine. Pantheizing God is no less troubling than anthropomorphizing or mythologizing him.

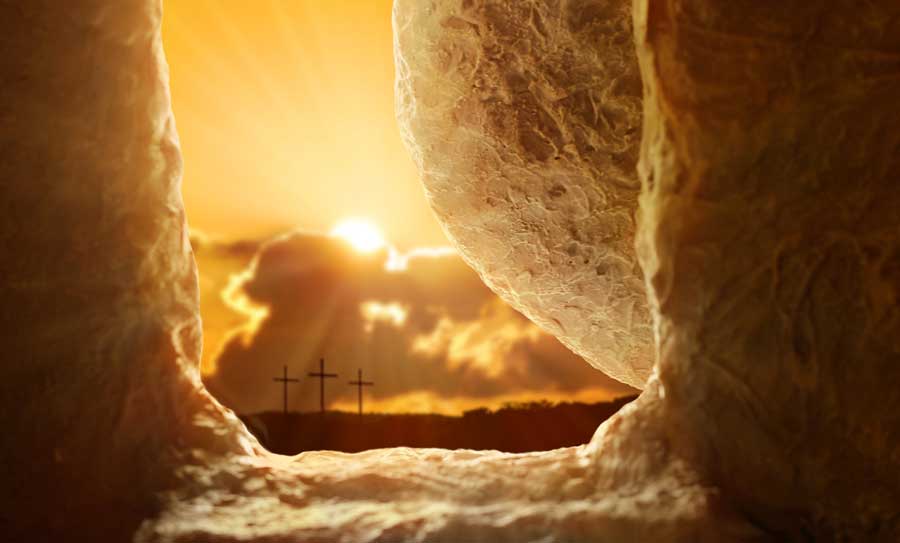

And yet. Christianity is not Gnostic. Christians believe in the body as created by God, assumed by God, and raised up by God. And if human bodies matter from exitus to reditus, from beginning to end, then perhaps we ought to think again about whether God, too, might be embodied.

Creation Echoes Incarnation

Our reflections should take their starting point, it seems to me, in the second of the three Christian beliefs just mentioned: the Incarnation. God assumes a body in Jesus Christ. The Chalcedonian Definition (451) serves as the benchmark for an orthodox understanding of the two natures of Christ as unconfused, unchanged, undivided, and inseparable in the one person of the Logos or Word of God. The Incarnation tells us that the eternal Word of God has taken upon himself a human nature—body and soul. We most truly know God in and through his condescension in the humanity of Christ, and we best understand man through his deifying union with God in Christ. God is known in man, while man is known in God. God is embodied—at least in Jesus Christ.

But Chalcedon teaches us something also about God’s general way of doing things, whenever he reveals himself: God’s typical, paradigmatic way of acting is Chalcedonian in character. Chalcedon, therefore, says something not just about the Incarnation, but also about creation: as a theophany of God, creation echoes the truth of Chalcedon. Maximus the Confessor reflects on this echoing of the Incarnation in creation: “The Logos of God (who is God) wills always and in all things to accomplish the mystery of His embodiment” (Ambigua 7.22). Note that Maximus uses the language of “embodiment” (ensōmatōsis). Creation embodies God because it is a manifestation of God, a theophany. The Orthodox theologian Philip Sherrard uses this same Maximian language in The Rape of Man and Nature when he states that “God is always seeking to work the miracle of His incarnation in all men” (22). The reason creation teaches us about God is that God embodies himself in it: creation echoes Incarnation.

To be sure, the Incarnation is unique and unrepeatable. But the embodiment of God in Christ does not preclude his embodiment in creation. Russian philosopher and theologian Semyon Frank asks rhetorically:

The perfect, stable and harmonious combination and balance of the Divine and human natures in [Christ], “without division and confusion,” is exceptional and in that sense miraculous—but does this imply that there can be no other form of combining these two principles in human personality? (Reality and Man, 140)

We should answer Frank’s rhetorical question with a resounding “No.” Indeed, I think God’s embodiment in Christ entails his embodiment also in creation.

Hans Boersma is the Saint Benedict Servants of Christ Professor in Ascetical Theology at Nashotah House Theological Seminary.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Theology from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor