To Strut & Fret an Hour Upon the Stage

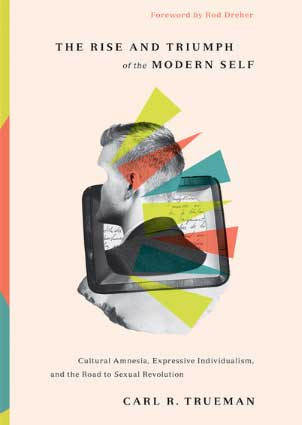

The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution by Carl R. Trueman

In The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution, Carl Trueman, professor of history at Grove City College, has written what I call a "mountaintop work." I refer not just to its intelligence and breadth of learning, but to how it works in the mind of the reader. Like Joseph Pieper's Leisure: The Basis of Culture, C. S. Lewis's The Abolition of Man, and Christopher Lasch's Culture of Narcissism, this work takes you to the summit of a great height, from whose vantage the many wandering roads, woods, streams, farms, and hills below, a seeming confusion of the arbitrary and happenstance, resolve themselves into order, so that you see not only what your guide points out to you, but plenty of other things as well, and not individually, but in all their many and often unexpected relationships. It reveals a world—or in this case, an anti-world.

Trueman's thesis, if I may be permitted an utterly inadequate condensation, is that contemporary man is a "self," whose existence is self-fashioned, not given by nature or culture or God, a self that acts upon the inert and otherwise meaningless stuff of the body, just as our sophisticated tools act upon the inert and meaningless stuff of what used to be called creation. Such a self therefore requires, as an inherent right, as an affirmation of its dignity, the stage of its choosing, whereupon to display itself. We are all peacocks now, I might jest, except that that does an injustice to the worthy peacock, who spreads his many-eyed plumes to the sun for the most earthy and natural of reasons, to win the heart of the peahen, that there should be more peafowl in the world. Better said, perhaps: we are all hypocrites now, letting everyone know what our right hand and left hand and other members farther south are doing, because if we fail to make that display, we cease

to be.

Tools of Our Tools

The malady is of no recent date, as Trueman shows. We have been nailing up the stage, as he sees it, at least since Rousseau, Blake, Wordsworth, and Shelley. But why not since man first strutted upon the earth? Here Trueman, building upon the work of Charles Taylor and Philip Rieff, draws a distinction between the play that echoes, by mimesis, a nature that is stable and given and beheld more or less with gratitude, and the play that denies that there is any such nature, but makes itself: poiesis.

"Art is but Nature to advantage dressed," says Pope, and he is talking not about daffodils, but about us, for "the proper study of mankind is man." "The purpose of playing," says Hamlet to the actors who have come to Elsinore, "is to hold, as 'twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure" (Hamlet, III.ii). Hamlet assumes that there is such a thing as virtue, that it does not change, and that it is the duty of the artist to portray virtue's lineaments faithfully and potently.

His advice might well have been uttered sixteen hundred years before him, by Horace for example, whose Ars Poetica begins with satirical remarks on what is not good poetry, namely, what violates the nature of things, as if "snakes could be the twins of birds, or sheep the twins of tigers." Philip Sidney goes farther, saying in his Defense of Poesy that although nature gave us a Cyrus, Xenophon in his art that built upon nature "bestow[ed] a Cyrus upon the world to make many Cyruses, if they will learn aright why and how that maker made him." We read about the poetically heightened Cyrus in order to engage in mimesis of our own, imitating his wisdom and public-minded virtue.

You will notice that nowhere do Horace, Sidney, Shakespeare, or Pope locate poetry in their subjective feelings. It is most true that poetry stirs the passions, as Sidney freely affirms; indeed it is meant to do that, and thus it is more effectual than moral philosophy, which can tell you what the right thing to do is, but has not the imaginative power to rouse you to do it. But that poetry, or any other human activity for that matter, should essentially be about the making and displaying of your own feelings, thereby to become a person in full, neither Sidney nor the oft-misread Shakespeare of the sonnets could believe for a moment.

Yet, as Trueman shows, that is what we all now take for granted, even Christians. We are thus all the inheritors of ugly brothers of one birth: the cold, mechanistic, and ultimately utilitarian rationalism of the Enlightenment, and the apparent rebellion of the Romantics. Science—reduced to what can be measured and manipulated—gives us the only truth, except that which we feel "authentically" from within us, about which neither physics nor biology, neither anthropology nor moral philosophy nor theology, can have anything to say. We are slaves to those natural sciences, because we do not affirm truths that they cannot reach, truths that are infinitely more important to our lives than is the chemical composition of ice; our false revenge upon those sciences is that we employ them, technologically, to help us fashion the selves we please. We are tools of our tools both ways.

The Sempiternal Orgiast

Given those assumptions, the sexual revolution was entirely foreseeable. For sex, more than any other feature of human existence, binds the physical to the social, the personal to the cultural; and sexual congress is the prime act whose meaning reaches far into both past and future. The child is born into this family, with these ancestors and these brothers and sisters and cousins, in this country, speaking this language; and he or she will likely marry in turn and perpetuate the line.

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor