Feature

The End of Liberal Democracy

Constitutionalism Without Christian Humanism

Modern teachers of political thought feel obliged to inform their students (almost invariably citizens of democratic republics) that the ancient political philosophers did not think highly of democracy. Certainly, they did not have the reflexive preference for it that we do.

Indeed, there has been quite a turn in the last couple of centuries. In a speech in Parliament in 1947, Churchill called democracy the worst form of government except for all the rest. In an essay titled "Present Concerns," C. S. Lewis said he was a proponent of democracy because he believed in the fall of man and felt that no man could be trusted with unchecked power. Reinhold Niebuhr wrote in The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness that "Man's capacity for justice makes democracy possible, but man's inclination for injustice makes democracy necessary." And William F. Buckley (himself a product of the Ivy League and one of its greatest debaters) quipped in Rumbles Left and Right that he "would rather be governed by the first two thousand people in the Boston telephone directory than by the two thousand faculty of Harvard University."

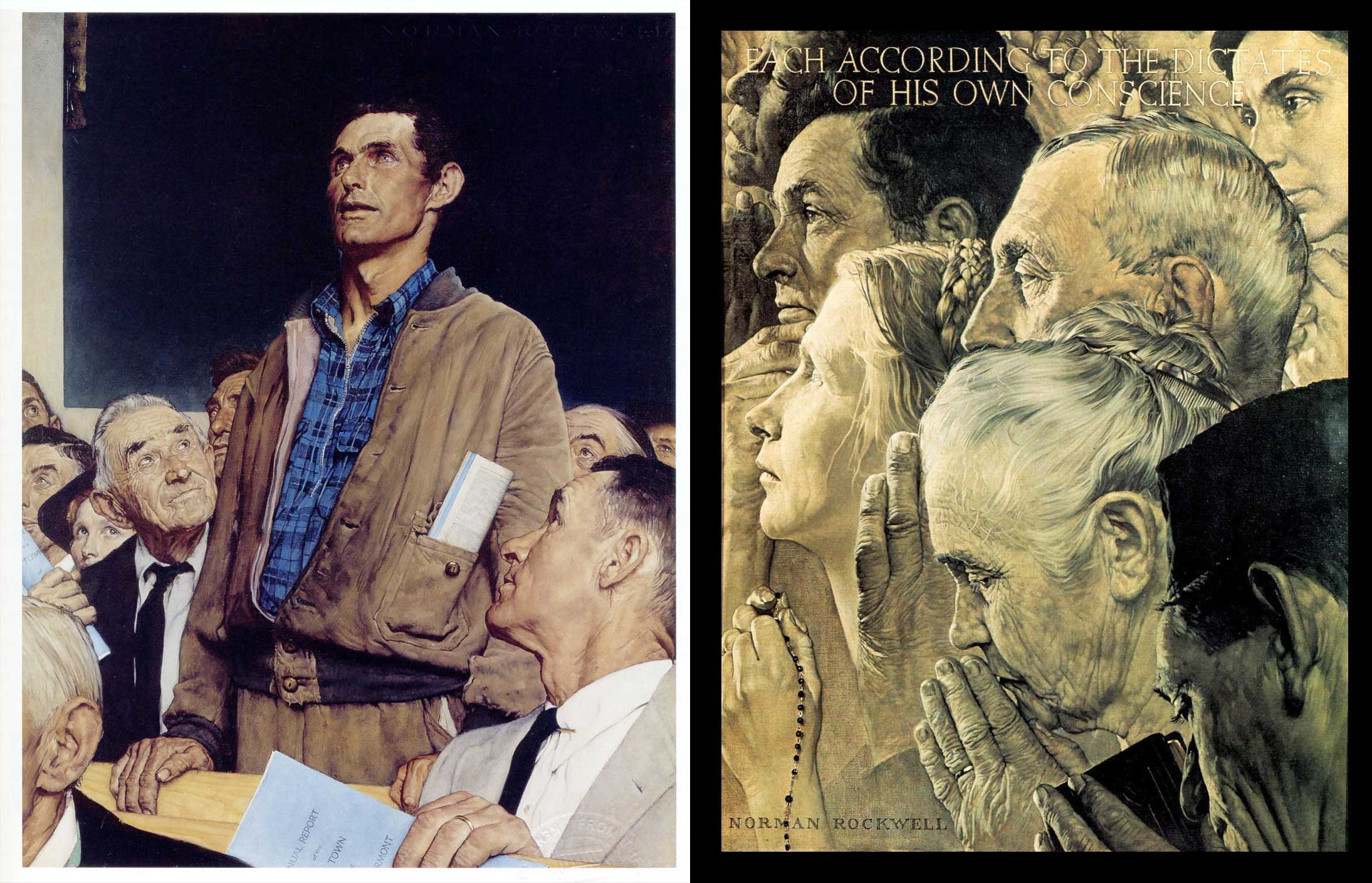

Our running assumption for at least the last century has been that democracy is possibly the only appropriate form of government for human beings, even if we understand its imperfections. When we evaluate another nation morally, we tend to look first to see whether the people who live there have the right to vote and the package of freedoms that typically accompanies the franchise, such as free speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of the press, and freedom of religion. So we have embraced not only democracy, but also a series of limitations on governmental power designed to keep the democracy from running roughshod over dissenters and minorities. In so doing, we have chosen the constitutional form of democracy over dreaded mob rule. The ancients would have approved of that much.

The Story of the Turn

I suggest we ask what explains the strong turn toward democracy in the modern world and then analyze the sustainability of the trend long-term. It is a story substantially influenced by the fusion of classical thought and Christian faith. We might begin with the idea of the human being as a creature bearing the image of God. All men share this nature. Cicero spelled out a similar understanding in his brilliant Dream of Scipio, in Book 6 of On the Commonwealth. In this passage, the grandson of a great Roman general has a vision that transports him beyond the earth into the cosmos. There he is able to perceive the common lineage of human beings under God, as manifested by their possession of reason.

In The City of God, Augustine brilliantly analyzed the impact of sin on human equality by noting that the desire to dominate is rooted in our fallen, self-serving, self-elevating nature. Rather than seek real peace with our brothers and sisters, we claim that our own desires represent peace. But real peace requires justice. And justice requires taking account of the dignity and rights of others. That reasoning fits nicely with Aristotle's observation in The Politics that men are poor judges of their own cases.

In all of this, we can see the foundations of constitutional democracy taking shape. Ideally, we give and receive consideration, while putting rules in place to curb our passions and self-interest in light of our capacity for self-deception and for disregarding rights beyond our own.

Democracy depends upon more than acknowledging that man is the kind of creature that may deserve the opportunity to participate in governing. The ability to participate is important as well. Practical components (such as the technology of the printing press) joined spiritual, theoretical, and ideological components in the sixteenth century, as Renaissance and Reformation thinkers emphasized primary texts (including the Bible), the translation of texts into vernacular languages, and the project of universal literacy.

The Bible's prominence in a period of broader access to printed texts served to radically increase the power of growing democratization and constitutionalism. Because the Bible was seen as an authoritative text, a populace capable of reading and understanding it could hold leaders and each other to account without relying upon a clerical hierarchy compromised at times by its sometimes cozy relationship with secular powers. A saying from that period held that a ploughboy with Scripture on his side might have the better of a prelate. Put more bluntly, scriptural Protestantism put constitutionalism on vitamins and substantially elevated the potential of the people to take a larger role in governing.

Having offered this account of how democracy overcame its bad reputation and helped lead us into this world of greater equality and self-governance (with the help of Christian and classical insights), what is there to say about democracy's prospects? Shouldn't the future be bright for democracy as we become healthier and wealthier?

Hunter Baker , J.D., Ph.D., is the dean of arts and sciences at Union University, a fellow of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, and an affiliate scholar of the Acton Institute.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on America from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor