Feature

All One in Christ

Why Christian Platonism Is Key to the Great Tradition

It’s hip to be a traditionalist. Retrieval theologies of a variety of colors, shapes, and sizes are the in-thing. It is hardly any longer just the Orthodox that turn to the church fathers. Nor is ressourcement of the Great Tradition simply the reserve any longer of mid-twentieth-century Catholic theologians such as Henri de Lubac, Yves Congar, and Hans Urs von Balthasar. Protestants, too—especially, it seems, of the Evangelical variety—have a newfound love of patristic and medieval theology and are intent on retrieving its riches for the church today.

I think this is a great development. Only the entirety of the witness of the Christian tradition is going to suffice to counter secular modernity’s amnesia regarding the past. I often hear the objection that many of today’s attempts at retrieval are only half-baked. That is to say, we often take a pick-and-choose attitude toward the tradition, selecting the liturgical elements that appeal to us most, implementing only those historic practices and disciplines that we can relate to, and selectively rummaging the theological toolbox of the church’s history. The result is a subjective pastiche that suits the sensibilities of our day. In other words, our retrieval of the Great Tradition allegedly plays postmodern hopscotch with our sacred past.

There’s no denying that the objection carries an element of truth. The complaint overlooks, however, the rationale behind the (admittedly sometimes partial and erratic) turn to the tradition. What drives recent theologies of retrieval is a deep longing for identity. It’s a desire to be linked with the past. Continuity with the past generates identities of solidity and strength.

In an age where everything seems fluid, transient, and discontinuous, people turn to tradition in the hope of rebuilding the continuity that is needed for stable identity. The intuition that it is by retrieving the Great Tradition that we rebuild and retain personal identity strikes me as profoundly true. Retrievals of the past are never perfect, but the basic impulse is one we should applaud.

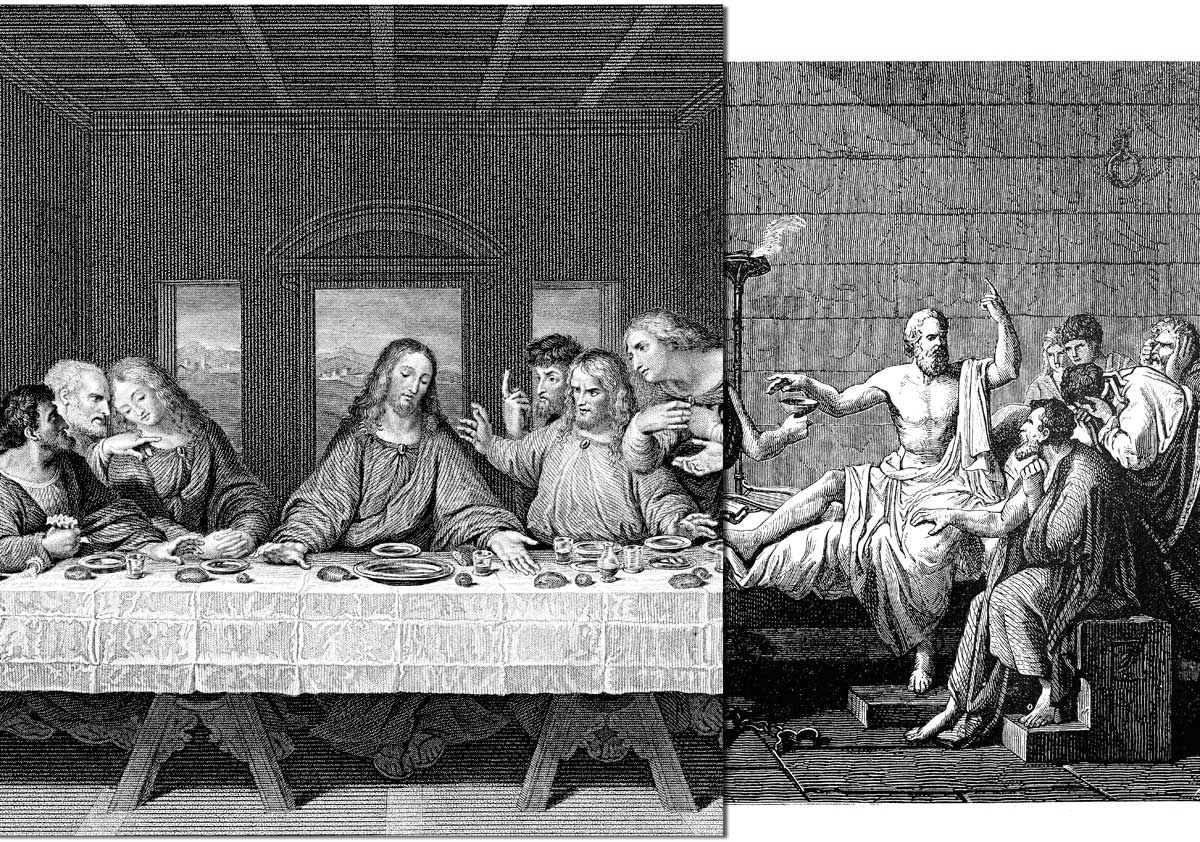

And yet. No matter how much sympathy I may have with the often less-than-perfect turn to tradition, there’s one element in the retrieval of the Great Tradition that just isn’t up for grabs: it’s Christian Platonism. Put bluntly, without Christian Platonism, retrieval isn’t true retrieval. Without Christian Platonism, re-appropriation of the Great Tradition just isn’t worth the effort.

Problems in Platonism

I often encounter a great deal of agreement and support when I raise my voice in support of a retrieval of the Great Tradition. Whether it’s candles in church, the adoption of the liturgical year, the meditative practices of lectio divina, or theological reading of Scripture, people regularly applaud these and other elements of the Christian tradition. The notion of Christian Platonism, however, frequently evokes a different kind of reaction. Even those most vocal about the need for the Christian tradition to help shape church and society today fall silent when it comes to the benefits of Christian Platonism.

The reason people give Christian Platonism the cold shoulder is typically twofold: one, it’s unbiblical; and two, it’s otherworldly.

The charge that Christian Platonism is unbiblical usually means something like this: Platonism is a pagan philosophy, so when Christians read Scripture through a Platonic lens, they impose a pagan outlook on their interpretation of Scripture. In other words, the mixing of Hellenism with Christianity by way of Platonism adulterates the purity of the biblical truth. We can’t have the Bible plus Plato. Authentic Christianity is grounded on Scripture alone (sola Scriptura).

The complaint that Christian Platonism is otherworldly offers a specific instance of how the use of Platonism allegedly adulterates the Christian faith. Whereas the Scriptures insist that God created the world good, the dualistic escapism of Platonism tempts us to turn away from this world to an ideal world of forms. The otherworldliness of Christian Platonism, therefore, is a denial of the goodness of creation.

Hans Boersma is the Saint Benedict Servants of Christ Professor in Ascetical Theology at Nashotah House Theological Seminary.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on philosophy from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor