A Thousand Words

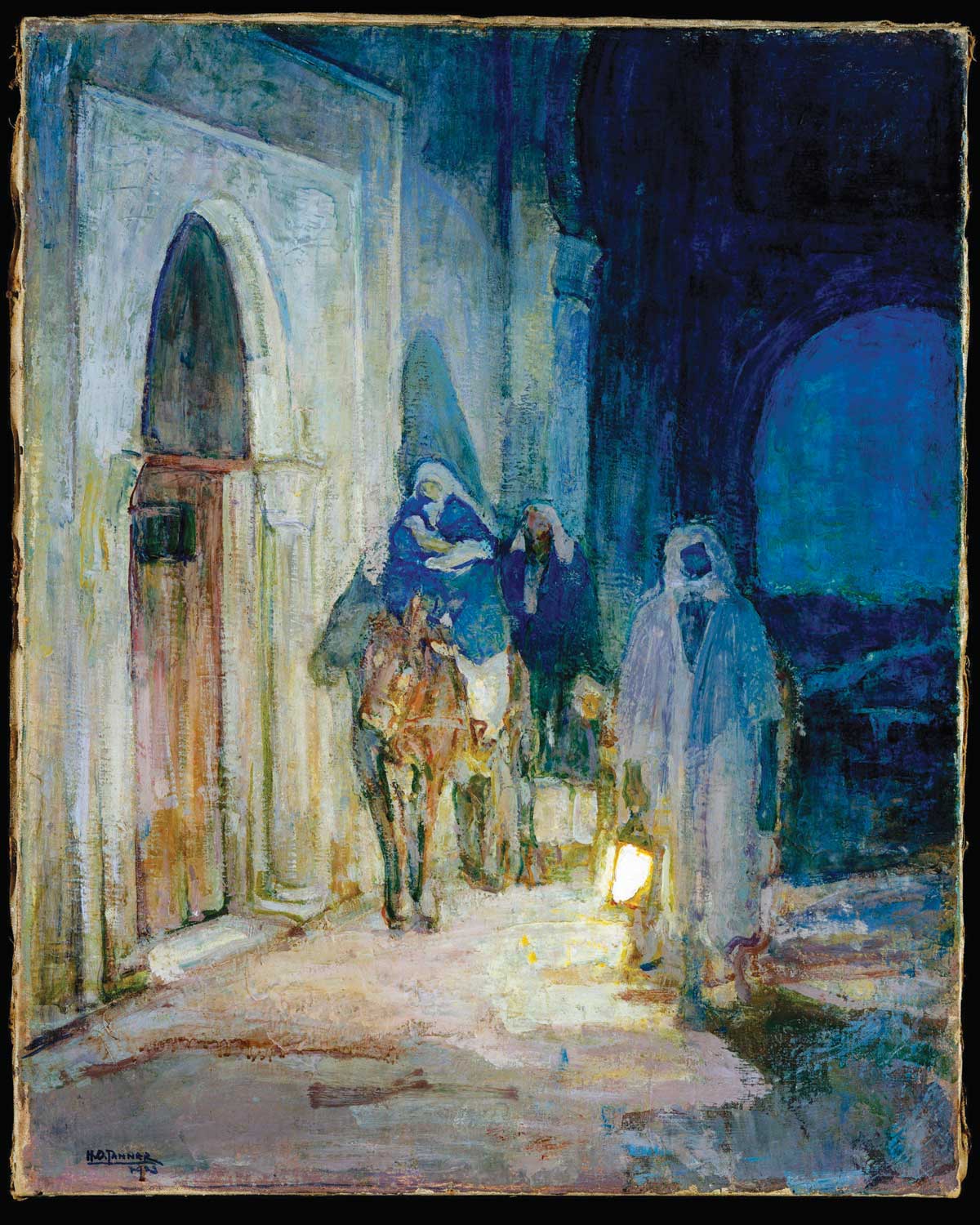

Henry Ossawa Tanner's The Flight into Egypt

by Mary Elizabeth Podles

The Flight into Egypt was probably Henry Ossawa Tanner's favorite Bible story. He painted at least four versions during his long career, usually depicting the Holy Family fleeing across open country. This version, his last, depicts an entirely different moment in the story. In this painting, the main characters are huddled against a wall, Mary and the Child on a donkey and Joseph behind them in the shadows. They are hemmed in; in front of them is a door, but it is shut and the window is barred. Behind them is an open arch showing just the suggestion of a dark landscape beyond.

In the foreground, the dominating figure is a robed and muffled man holding a lantern. It is hard to know how to read this figure. Is he a menacing presence? A watchman to be eluded as Joseph flees by night? Is this a moment of awful danger? The Holy Family could be frozen in fright. Or is he an angelic figure come to light their way? In Matthew's account, Joseph is warned by an angel in a dream, and takes the child and his mother away by night. The artist, late in life, favored a restricted palette of blues such as we see here (they came to be known as "Tanner blues"), and the only hint of warmth in the darkness comes from the golden light of the lantern and the browns in the light it casts. So perhaps this is a protective presence instead of a menace.

Turn to Biblical Subjects

It might help to decipher the painting if we look at it in the context of Tanner's whole body of work. As an African-American, Tanner had encountered opposition and difficulty in establishing himself as an artist, but due to a generous benefactor he was able to leave the U.S. for France. There he found expert artistic instruction and, in his bohemian circle of artists, a more egalitarian society. At first, he painted scenes from ordinary life, often African-Americans, whom he represented as serious and dignified figures, never comic ones. Then, around 1896, Tanner abruptly shifted to painting biblical subjects.

There has been considerable speculation about the reason for his sudden change. Tanner was the son of an AME clergyman and eventually bishop, so his childhood must have been steeped in biblical lore. In France, Tanner spent the summers in Brittany, among the artists of the Pont-Aven school, who often drew upon the Bretons' deep religious sentiments for their paintings; even the irreligious Gauguin painted scenes with religious themes while there. Also at Pont-Aven, Tanner acquired the Post-Impressionists' taste for pure color, and for a flattening of form and constriction of space such as we see in the Flight into Egypt. Some suggest that his religious paintings were analogies with his struggle for racial equality. Ambition may have played a part, too. History painting, which includes mythological and biblical subjects, was held in higher esteem than genre painting, and was more salable at the time. In fact it was his large paintings, Daniel in the Lion's Den and The Raising of Lazarus that first won him public acclaim.

Recent scholarship, however, suggests more personal reasons for Tanner's turn to biblical subjects. In general, he was a very reticent man, and even in his autobiography he writes with great restraint about his private thoughts. But in a Christmas letter to his parents, he speaks of a spiritual crisis, the need for repentance and a return to grace, for which he seeks divine intervention and a renewed closeness to God. From then on, his paintings illustrate just that: Daniel, the man of faith, is miraculously delivered from the lions; Lazarus is raised from the dead by Jesus' intervention. The various renderings of the Flight into Egypt show us Joseph, the man of faith, trusting divine revelation to save Jesus from Herod's assassins. These themes may have held a further personal resonance for Tanner: his mother was born in slavery, but was brought north at the age of eleven by the Underground Railroad.

Depression & Deliverance

The Flight into Egypt under consideration here dates from late in Tanner's career, from 1923, after religious paintings in general had fallen out of fashion and he was in his declining years. World War I had been a devastating experience for him. He lived near the awful destruction in the north of France and had worked for the American Red Cross. The experience drove him into a deep depression. Again he felt the need for miraculous intervention, for an escape from persecution and horror. Thus, we can read the figure in white as a salvific figure, leading the man of faith and his family out of danger by the light of the divine.

Tanner's faith was renewed. He wrote of his religious paintings,

I have no doubt an inheritance of religious feeling, and for this I am glad, but I have also a decided and I hope an intelligent and religious faith not due to inheritance but to my own convictions. I believe my religion. . . . I have chosen the character of my art because it conveys my message and tells what I want to tell to my own generation and leave to the future.

Mary Elizabeth Podles is the retired curator of Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. She is the author of A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity (St. James Press, 2023). She and her husband Leon, a Touchstone senior editor, have six children and live in Baltimore, Maryland. She is a contributing editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on art from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor