Feature

The Habit of Community

Reception, Gratitude, & Witness on a Christian Campus

“I will sing of the steadfast love of the Lord forever! With my mouth will I make known your faithfulness to all generations!” (Psalm 89:1). These words of the Psalmist express the heart of what I want to say here—and, indeed, contain the essence of the title I’ve given these remarks: “The Habit of Community.” Before we unpack the Psalmist’s words, however, I want to back up a bit to get a few ideas on the table.

T. S. Eliot has made me more sensitive lately to noticing the patterns of life. His Four Quartets is primarily concerned with being able to see something he calls “the still point”—those moments in which we get a flash of insight into the intersection between the eternal and the temporal. In these moments we can see how we are called in the midst of our human frailty into fellowship in the life of God. Some of us are called to contemplative vocations devoted to attending to such insights, but for most of us, Eliot observes, the divine breaks through—the meaning of our existence emerges—in the patterns of life: “prayer, observance, discipline, thought and action.”

Of course, we have patterns that structure our life together here in the Torrey Honors Institute. There are those times when there’s a massive migration to turn in the first submission of the Torrey paper at 4:30 on a Friday afternoon—or the semesterly ritual of hauling all your books across campus to Don Rags [final oral exams] and standing around in the hall like you’re at a doctor’s office waiting to have your tonsils removed. In those moments, you realize, “Hey, we really are all working on a common project—pursuing wisdom as a common good.” This convocation is a pattern, too, a time at the beginning of the year when we come together to commit ourselves to pursuing with whole hearts what God has given us to do.

Some patterns are only noticeable to faculty because we don’t really move through the curriculum but get to swim around in it year after year. One pattern I love is reading Homer every year with the incoming freshmen. It strikes me that there’s something uniquely illuminating about beginning our journey together into the great tradition with those words that ring down through the centuries: “Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilleus / and its devastation, which put pains thousandfold upon the Achaians.” I think, in fact, one of the deep veins of wisdom in the Iliad turns out to be a justification of the whole project we’re engaged in together here. So let’s spend a few minutes thinking together about the Iliad.

Facing Mortality

Achilles first appears to us as a man driven by his passions—first by his desire for honor, and subsequently by his fierce anger when that desire is disregarded by Agamemnon. The problem is not that Achilles defends his honor or is enraged at Agamemnon’s high-handedness. That makes perfect sense in the Homeric economy, where honor and glory cut to the heart of the warrior’s worth. The distinguishing feature of Achilles’ rage is that it is unrelenting. And it’s not just that he’s a really, really stubborn guy. His implacability exceeds all human proportion. It even goes beyond that of the gods. Thus, Achilles’ aged guardian, Phoenix, pleads with him: “Achilles, beat down your great anger. It is not yours to have a pitiless heart. The very immortals can be moved; their virtue and honor and strength are greater than ours are—and yet . . . men turn back even the immortals in supplication” (IX.500).

Achilles’ rage outstrips even the gods because he lusts for their immortality. And we can understand this, right? Solomon tells us that God has put eternity into all our hearts, and Achilles feels the pull of transcendence even more: his mother, Thetis, is a goddess. She’s a minor goddess, yes, and his father is a mortal. Still, Achilles feels his divine pedigree. Even among the Achaian and Trojan heroes, he’s like a god on the battlefield. Moreover, his mother has told him that he can attain everlasting glory if he dies on the plains of Troy. So Achilles yearns for immortality—and thus Agamemnon’s insult is caught up into a narrative that transcends the lives and suffering of mere mortals. Achilles wants to be a god. So when Agamemnon treats him like a hired hand, he’s willing to burn it all down—deaf and blind to the suffering of his own people.

The trouble is that Achilles is not immortal. He is a man doomed to die and to live a life marked by death. It is not until the Odyssey that we see the final humiliation of his longing to be more than he is. Yet, within the narrative of the Iliad, his greater-than-Olympian rage is twice undone by the deep wounds of death. First, the death of his dear friend Patroclus shatters his inhuman aloofness from suffering, and he returns to the battlefield. And second, the painful memory of his own father’s death awakens him to the suffering of Hector’s father, Priam.

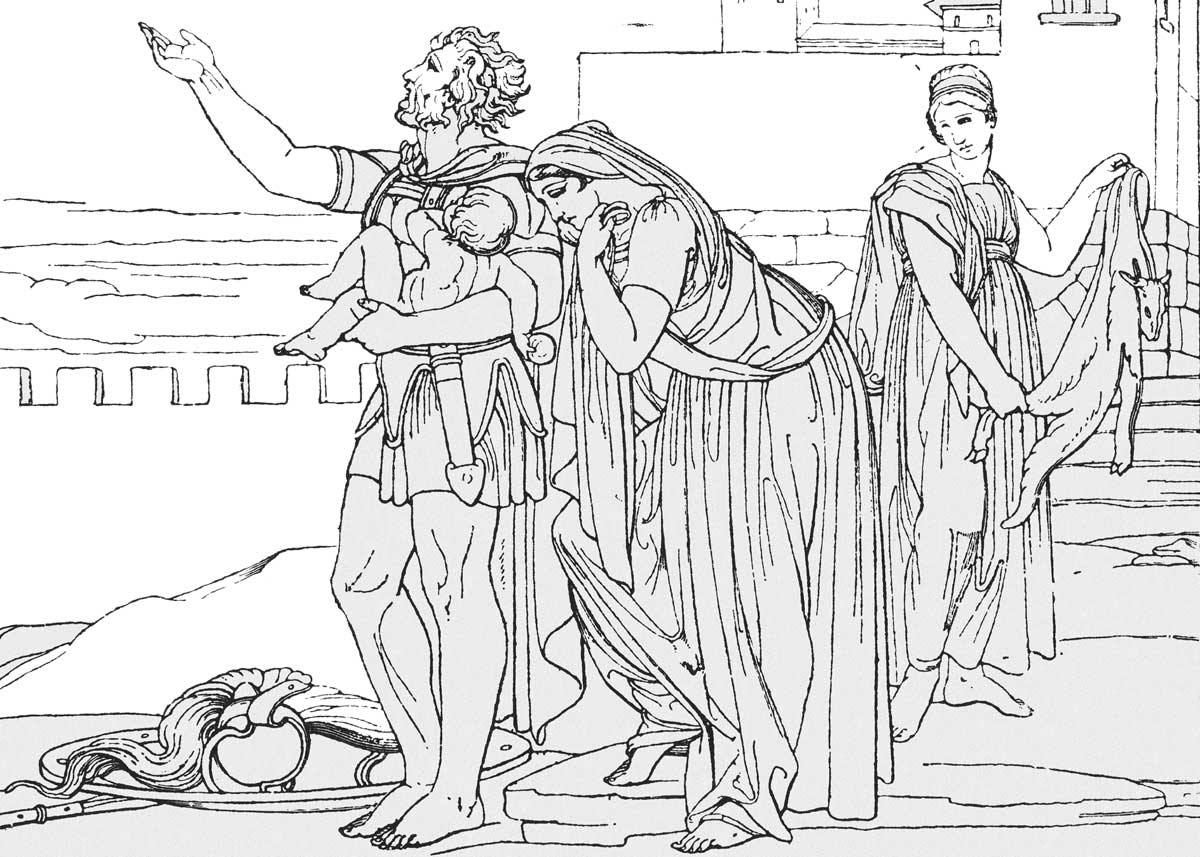

In the embrace of Priam, Achilles returns to his humanity, his capacity for mercy, for fellow feeling—and, perhaps above all, he is stripped of his pretense to divine self-sufficiency. He regains, at least in this moment, his ability to participate in a human community—as a mortal marked by suffering and death. Thus, every year, year in and year out, we begin our journey together into the Great Conversation with this piece of wisdom: To understand what it means to live in community, and to practice it well, requires that we face squarely the truth of our mortality.

A Generational Focus

Matthew D. Wright is an associate professor of government in the Torrey Honors Institute at Biola University and the 2019-2020 John and Daria Barry Visiting Research Scholar in the James Madison Program at Princeton University.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on literature from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor