Feature

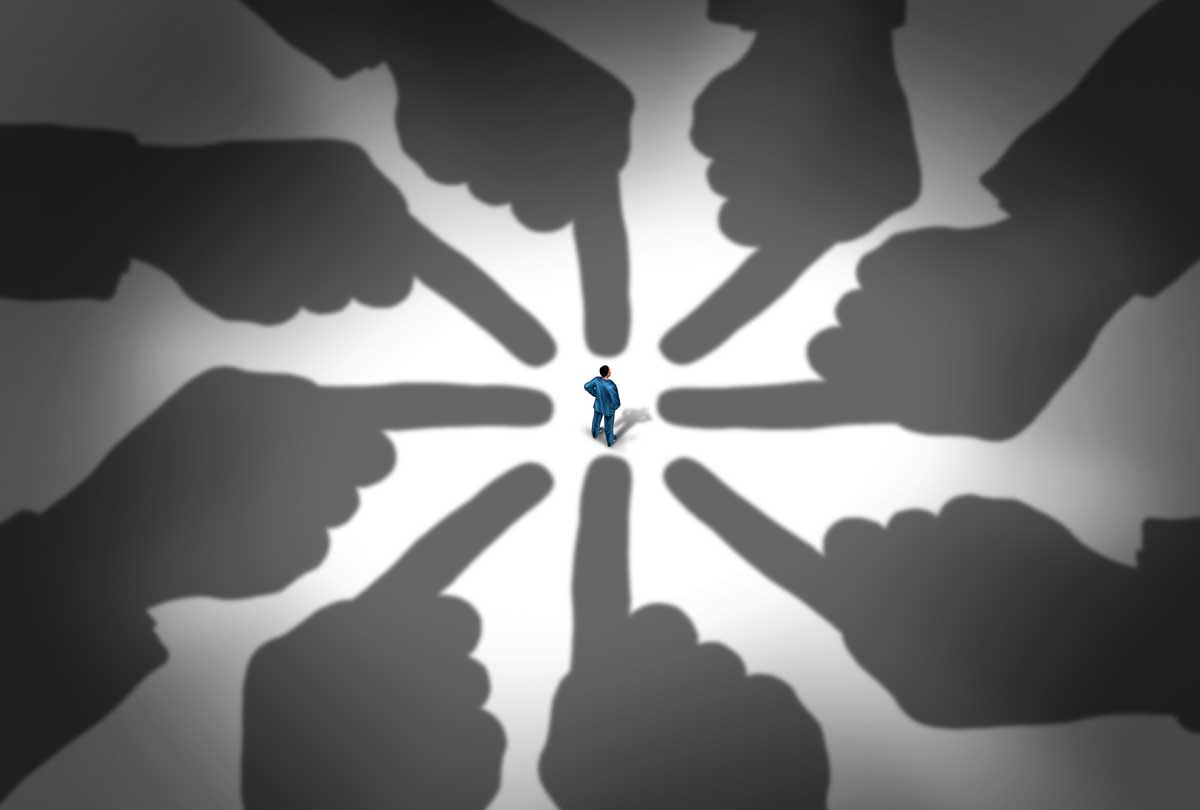

Virtue Gone Mad

Victimhood Culture Scapegoats Its Very Source

It was Harvey Mansfield who voiced the notion that you can tell who is in charge of a society by noticing who is allowed to get angry and for what cause. Donald Trump certainly gets angry, but given the chilly disdain for his splenetic tweets and polemical rhetoric, it does not appear that he is allowed to by those "in charge of our society." The U.S. Catholic hierarchy and other Christian leaders, on the other hand, seem to be acutely aware of the Mansfield principle, and thus they avoid public displays of righteous anger unless the cause is likewise promoted by those "in charge"—for example, social justice issues.

So who, then, is in charge? Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning provide a partial answer to that question in their 2014 article in Comparative Sociology, "Microaggression and Moral Cultures," and in their 2018 book The Rise of Victimhood Culture: Microaggressions, Safe Spaces, and the New Culture Wars (Palgrave Macmillan). The authors' thesis is that the embrace of victimology that began in the 1960s and 1970s has given rise to a new "culture of victimhood." Like any other moral culture, victimhood culture offers a framework for resolving conflict and awarding praise or blame. But in crucial respects, victimhood culture is unlike any other, past or present.

Honor & Dignity

To highlight its distinctive features, Campbell and Manning contrast victimhood culture with two other cultures from American history: the "honor cultures" of the American Revolution and antebellum South, and a "dignity culture" that reached its height in the Midwest in the 1950s.

In honor cultures, men are highly sensitive to insult (hence the prevalence of duels). They like to call attention to themselves, especially to their prowess or exploits in areas involving conquest or risk, and they like to do so not only with respect to virtuous acts of bravery but also with respect to vicious acts such as gambling, drinking, and philandering. Honor seekers do not hesitate to exaggerate their successes or even lie about them, for by maintaining the appearance of being a victor in conflicts, they maintain their status and intimidate competitors. Honor cultures are tight-knit communities where word of mouth and age-old custom prevail and where supervening legal authority is disdained. Men of honor may love their family and their country, but they scorn the government or the court system, for there is more glory in resolving conflict through one's own skill or bravery than by invoking the help of a third party.

In a culture of dignity, on the other hand, individual dignity is seen as an inherent and inalienable good that one does not need constantly to prove or assert as in an honor culture. Consequently, in a dignity culture it is considered unnecessary and distasteful to draw attention to oneself. Insults no longer provoke wrath as they do in an honor culture: the phrase "Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me" nicely sums up a dignity culture but is unthinkable in an honor or, as we shall see, victimhood culture. Dignity cultures have a stable and powerful third-party legal system, but the goal is to use such a system as quietly, discreetly, and as rarely as possible. Self-restraint, toleration, and peaceful confrontation are the hallmarks of a dignity culture.

Competitive Victimhood

A victimhood culture, by contrast, is an almost perfect photographic negative of an honor culture. Like honor cultures, victimhood culture is highly sensitive to insult. Today this sensitivity is enshrined in the use of terms like "microaggressions" and "trigger words," but the phenomenon predates the jargon. In the 1990s, Danusha V. Goska was a leftist when she read a passage from Caroline Myss's bestselling Anatomy of the Spirit. Myss, Goska later wrote,

described having lunch with a woman named Mary. A man approached Mary and asked her if she were free to do a favor for him on June 8th. No, Mary replied, "I absolutely cannot do anything on June 8th because June 8th is my incest survivors' meeting and we never let each other down! They have suffered so much already! I would never betray incest survivors!" Myss was flabbergasted. Mary could have simply said "Yes" or "No."

Reading the anecdote was an epiphanic moment for Goska, who immediately recognized the same proclivity to outrage among her leftist friends and allies.

Michael P. Foley is an associate professor of Patristics in the Great Texts Program at Baylor University and the author of The Politically Incorrect Guide to Christianity (Regnery, 2017).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

Support Touchstone

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor