Introduction

What is truth? John 18:38

"Pilate's cynical question still demands an answer," writes Donald Williams in his November 2018 article Meaningful Truth, "and [C.S. Lewis'] is especially helpful. . . . So how did Lewis answer that question, and what does imagination contribute?"

It is our imagination, Williams writes, that does the work of finding things meaningful. To the observer who is without imagination, it doesn't really matter what is true because everything is equally meaningless. I am reminded here of G.K. Chesterton who wrote, "Do not be proud of the fact that your grandmother was shocked at something which you are accustomed to seeing or hearing without being shocked. . . . It may be that your grandmother was an extremely lively and vital animal, and that you are a paralytic."

Next comes reason. Reason is how we talk about what our imagination finds meaningful. Without reason we cannot connect the dots and explain ourselves. Nor can we tell a story. Pilate's famous question demonstrates a profound failure of both his imagination (his failure to see the meaning behind the trial of Jesus) and his reason.

(It is Pilate's wife Procla who sees the meaning and reasons with her husband when she proclaims "Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much because of him today in a dream.")

This, writes Williams, is what Lewis means when he called reason the "organ of truth." Myth is the story that allows other imaginations to receive and taste a way of seeing the world that reason can then confirm as true or false. And finally, what is true is that part of these stories or accounts that corresponds with reality.

And so says Donald Williams in Meaningful Truth, from the November/December 2018 issue.

—Douglas Johnson, Executive Editor

(read more Editor's Picks)

Meaningful Truth by Donald T. Williams

Feature

Meaningful Truth

The Critical Role of Imagination in the Work of C. S. Lewis

by Donald T. Williams

After the storm there's a rainbow,

And all of the colors are black.

It's not that the colors aren't there;

It's just imagination we lack.

—Paul Simon

One thing that makes C. S. Lewis uniquely important as a Christian writer is the way he integrates reason and imagination in his expository writings as well as his fiction, all in the service of truth. But what is truth? Pilate's cynical question still demands an answer, and Lewis's is especially helpful because of the way it calls both Reason and Imagination into coordinated teamwork under Truth as their captain. So how did Lewis answer that question, and what does imagination contribute? It is more than just letting him write good stories to illustrate the truths he wants to communicate.

The Organ of Meaning

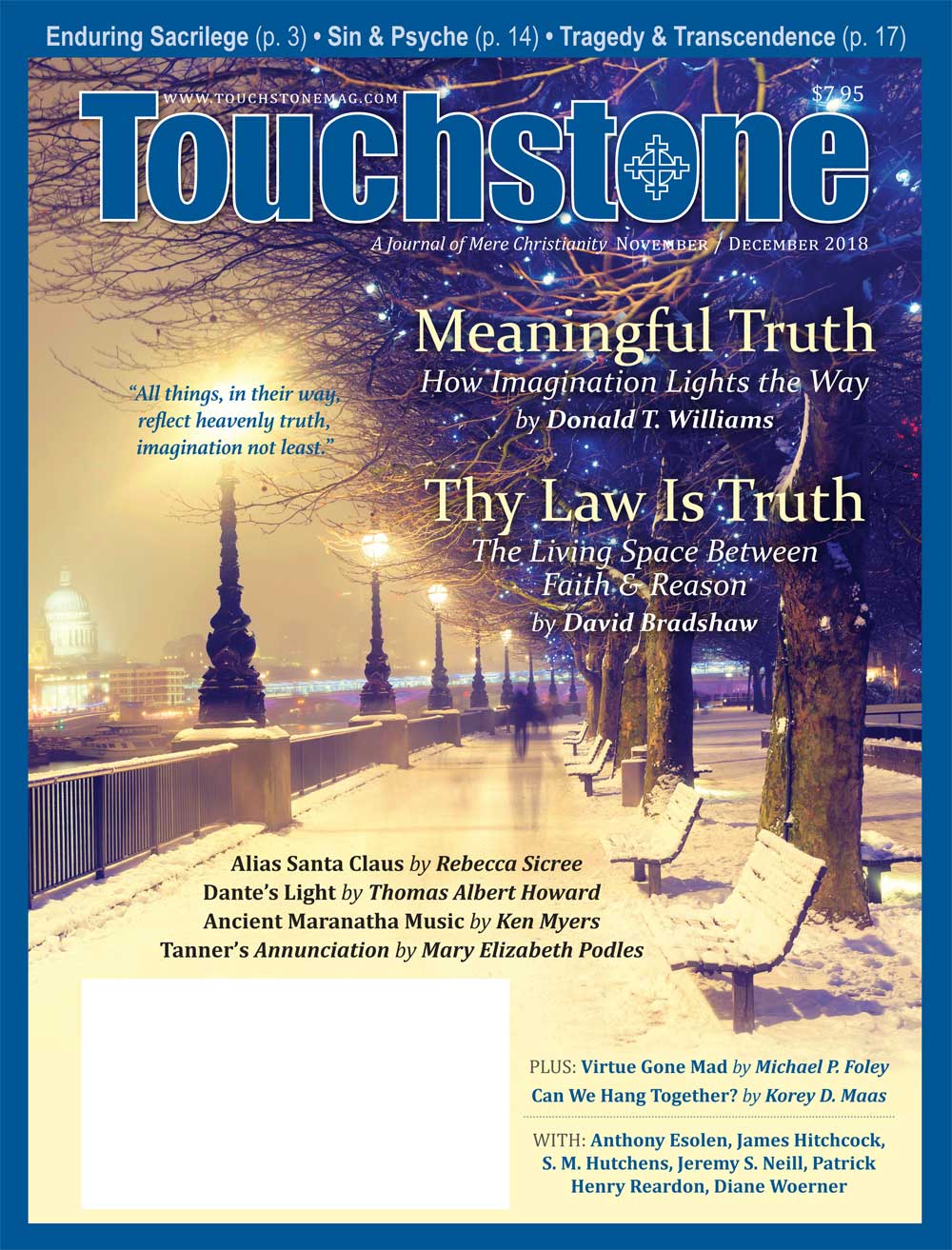

Lewis is solidly in the mainstream of Christian thinking about truth. Truth is a property of propositions such that they correspond with the state of affairs in the objective world that they purport to describe. Augustine and Aquinas, Calvin and Wesley, Cardinal Newman and Carl F. H. Henry would all have affirmed the same basic points, though not perhaps with Lewis's characteristically deft use of apt analogy. What Lewis adds to the discussion is some careful thinking about the relation of truth not only to reason but also to imagination. It was his experience and his conviction that "all things, in their way, reflect heavenly truth, imagination not least" (Surprised by Joy, 167). How exactly does imagination do so?

Some of Lewis's interpreters, influenced perhaps by the surface resemblance in language between Lewis and the English Romantics, have not paid sufficiently careful attention to the way Lewis answers that question. One reads statements such as "Lewis, like many Romantics, intuitively trusted the capacity of imagination to be a 'faculty of truth'" (Eliane Tixier, "Imagination Baptized," The Longing for a Form: Essays on the Fiction of C. S. Lewis, ed. Peter J. Schackel, 141).

What Lewis actually said when he analyzed the relation between imagination and truth was much more carefully and rigorously thought out:

We are not talking about truth but meaning: meaning which is the antecedent condition of both truth and falsehood, whose antithesis is not error but nonsense. I am a rationalist. For me, reason is the natural organ of truth; but imagination is the organ of meaning. Imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old, is not the cause of truth, but its condition. ("Bluspels and Flalansferes," Selected Literary Essays, 265).

Imagination is the faculty or organ not of truth (directly) but of meaning, which is the "antecedent condition" of truth. What does this mean?

Suppose I utter the proposition, "Blepple hloisats kleply flarg krunk bluzzles," and then ask you for a verdict on its truth or falsehood. I suspect you would be somewhat handicapped in trying to render that verdict by the minor problem that you would have no idea what I had said. Before you could even begin to form a judgment on the truth question, you would need to know what a hloisat is, how a blepple one differs from a regular one, what it is to flarg, what a bluzzle is, what is the quality of krunkness, and how flarging kleply differs from regular flarging. In order to give you that information, I would have to render these objects, qualities, and actions in concrete terms that you could visualize. Your imagination would be the faculty that enabled you to form a picture—an image—of what the proposition is asserting (or whether it is asserting anything). Then your reason could compare that mental picture to the picture of reality it has already tested and come to trust, in order to see if correspondence or contradiction resulted.

Imagination, in other words, doesn't give us truth. Reason for Lewis is the organ of truth. Just because we can imagine something does not make it real. But imagination combined with reason can give us meaningful truth, truth that impacts us on other levels besides mere intellectual assent. This is truth that can appeal to head and heart together. Lewis was the master of giving it to us, whether in his expository prose or his fiction. Examples abound: the hall and rooms of a house are an analogy for the Church and its denominations; two books that have always been resting one on the other for the eternal generation of the Son; the keys of a piano and a tune for the relationship between our instincts and the moral law; entrusting oneself to the waves and floating islands of Perelandra rather than sleeping on the fixed land for faith; the Stone Table for the Law and Aslan's death cracking it for the Gospel; Reepicheep the Mouse for valor, chivalry, and honor.

Continue Reading

Donald T. Williams is Professor Emeritus

of Toccoa Falls College. He stays permanently camped out on

the borders between serious scholarship and pastoral ministry,

between theology and literature, and between Narnia and

Middle-Earth. He is the author of fourteen books, including

Answers from Aslan: The Enduring Apologetics of C. S. Lewis

(DeWard, 2023). He is a contributing editor of Touchstone.

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS

full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone

online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

18.3—April 2005

Lions of Succession

on Being a Free Narnian & the Joy of Subordination by Donald T. Williams

33.2—March/April 2020

The Fairy Tale Wars

Lewis, Chesterton, et al. Against the Frauds, Experts & Revisionists by Vigen Guroian

more from the online archives

32.5—September/October 2019

Looking for Jacobs

Some Trivial Thoughts on the Study of Philosophy by Graeme Hunter

32.5—September/October 2019

Feral Sexuality

on the Inhuman Transformation of Transgenderism by Anthony Esolen

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor

Support Touchstone

00