A Thousand Words

Leonardo's Madonna and Child with Saint Anne

by Mary Elizabeth Podles

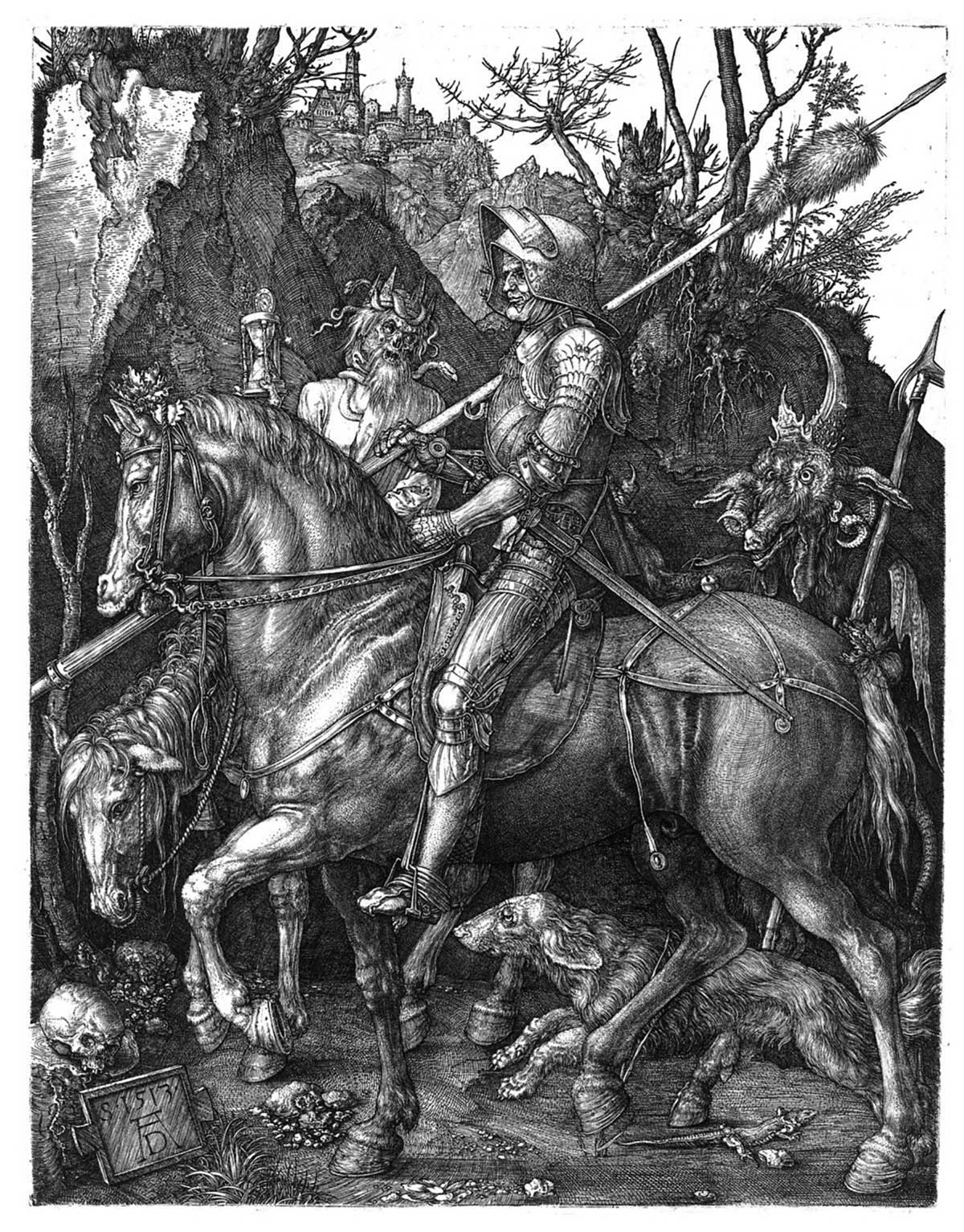

The Madonna and Child with Saint Anne has long been regarded as a problem picture, not only for us but also for Leonardo. The iconography creates a fundamentally impossible visual dilemma: how to combine two adult figures and a small child into a dramatic and unified whole, giving each one equal weight and successfully conveying the theological concepts they traditionally stand for. Earlier solutions like Masaccio's (Figure 1) imposed a medieval hierarchy of scale and at best created interlocking generational boxes to form a kind of human trinity of Christ's human genesis. Such a static devotional image did not satisfy Leonardo, who sought always for drama and a deeper exploration of theological meaning.

Nor were his first attempts satisfactory, at least to him. In 1499 he designed and drew a version of the subject (Figure 2) with Mary seated in St. Anne's lap and holding the infant Jesus, who in turn embraces a young John the Baptist. This version was never actually painted. A second design was executed in 1501 and described in a letter by Pietro da Novellare: there, Jesus was shown grappling with a lamb while Mary restrains him and Anne looks on. That version also was never painted, and the drawing is now lost. Our version was probably begun around 1510. It may have been commissioned by Leonardo's patron, Louis XII of France, at the birth of his daughter. His wife, Anne de Bretagne, had suffered a string of miscarriages and stillbirths; St. Anne, her name saint, was also the patron saint of childbirth. Whatever the commission, the patron was doomed to disappointment. The painting, still unfinished, remained in Leonardo's possession at the time of his death in 1519.

Leonardo's final solution resembles the one described in 1501: Mary is seated in her mother's lap, reaching out to her son, who grasps the lamb by its ear and attempts to straddle it. The figures are arranged within a strong triangular shape, its base firmly set on the ground and rising to the apex at Anne's head. Inside this stable pyramid, however, things get a bit more complex. Leonardo knits together the various serpentine figures and their gazes into a lively spiral motion that the scholar Kenneth Clark likens to "some very complex machine, designed to rotate and to be placed on a rotating platform." Yet within the complexity there remains a dramatic unity and a balance, if an asymmetrical one, enlivened by its internal variety of gesture and movement.

THIS ARTICLE ONLY AVAILABLE TO SUBSCRIBERS.

FOR QUICK ACCESS:

Mary Elizabeth Podles is the retired curator of Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. She is the author of A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity (St. James Press, 2023). She and her husband Leon, a Touchstone senior editor, have six children and live in Baltimore, Maryland. She is a contributing editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on art from the online archives

more from the online archives

19.10—December 2006

Workers of Another World United

A Personal Commemoration of Poland’s Solidarity 25 Years Later by John Harmon McElroy

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor