View

Beggars Before Christ

Martin Bordelon on Taking the Measure of the Deserving & the Undeserving Poor

Dorothy Day is remembered for, among other things, her belief that we should not distinguish between the "deserving poor" and the "undeserving poor." (While the exact quote articulating this seems to be apocryphal, the concept appears in several places in her writing.) She was, in her time, highly criticized for this position, and at first glance it seems like a perfectly reasonable criticism. Anyone who has ever spent a good deal of time working with the poor has probably experienced frustration. The problems of poverty frequently seem intractable, and this is sometimes due, at least in part, to the poor themselves. Drugs, alcohol, criminal activity, poor decision-making—all of these play a part in the cycle of poverty. When we realize this is the case, we are often tempted to give up. We see our resources being squandered by those we give them to, and it seems that at some point we just ought to say, "Enough!"

I experienced this feeling very acutely several years ago. There was a man my wife and I had known for a few years—he has since passed away—who had fallen on hard times and been left homeless. From the time of our first meeting with him, we had frequently lent him aid as we were able. We gave him money and supplies, drove him places he needed to go, and eventually—through some connections we had and the providence of God—were able to find him a permanent home where he was fed and sheltered in the best possible environment. I was frustrated, then, to see him still begging for money on the corner, even after so much had been provided for him. And I wasn't entirely sure what he was using it for, either. He did have legitimate uses for the money—riding the bus, for example—but at least some of it went towards the copious quantity of cigarettes he smoked, and he was occasionally evasive about his other expenses.

Nor was this the only frustrating thing. The habit of lying he had developed as a survival mechanism never left him (much to the embarrassment of his supporters), and his quick temper frequently put him in conflict with those around him. Such habits had caused problems for him in the past, and they sometimes hampered our efforts to help him.

I do not mean to speak ill of the dead. There were many redeeming qualities in the man we knew, and those who took the time to know him invariably found that he had a wonderful heart. But given the problems he did have, it would certainly be within reason to think that this man was among the "undeserving poor." After all, my wife and I had seen the other end of the spectrum as well. We had met people who, with a little bit of help—sometimes with money, sometimes with connections—had really been able to get back on their feet. They had no moral deficiency holding them back, only circumstances and a few runs of bad luck. How is it, then, that people like Dorothy Day see no distinction between the two?

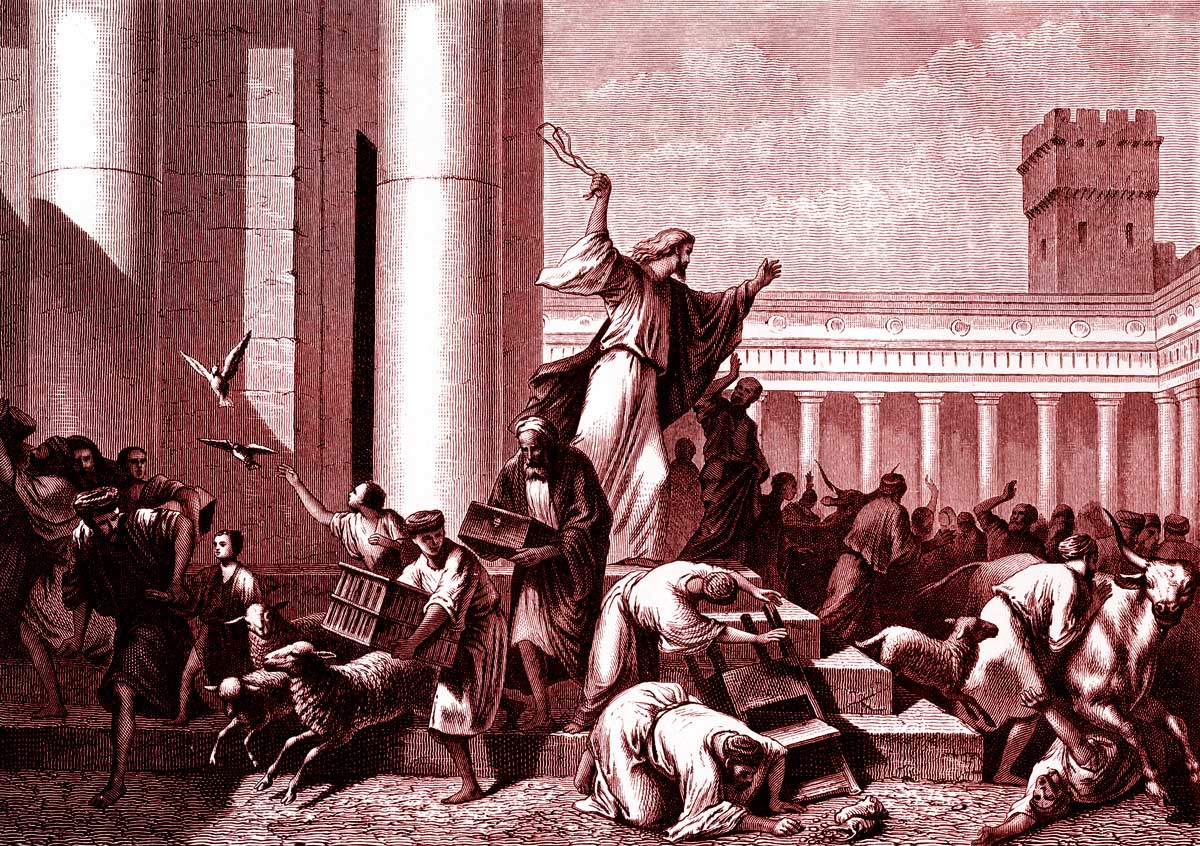

A Lesson from the Gospel

The key, I think, lies in the Gospel of Matthew. In chapter 18, Jesus tells the Parable of the Unmerciful Servant. In this parable, a king forgives one of his servants an enormous debt. The servant is grateful to his master, but when he has the opportunity to forgive a much smaller debt owed to him by one of his fellow servants, he cruelly refuses. The king is furious and reverses his previous policy of mercy, throwing the first servant into prison "until the last penny is paid."

It is often said of the "undeserving poor" that they are a "burden on society." To put this another way, they owe society a debt. This was certainly true of the man we helped. Yet if we believe the Parable of the Unmerciful Servant, then we know that the debt they owe to society is far, far smaller than the debt we owe to God. It may be that the poor are undeserving of our help, but it is certain that we are undeserving of God's help. It may be that the poor misuse the gifts we give them, but it is certain that we misuse the gifts of God.

As Benedict XVI astutely observes in the first volume of his Jesus of Nazareth series, every parable involves "a twofold movement":

On the one hand, the parable brings distant realities close to the listeners as they reflect upon it. On the other hand, the listeners themselves are led onto a journey. . . . The parable demands the collaboration of the learner, for not only is something brought close to him, but he himself must enter into the movement of the parable and journey along with it.

In other words, parables always draw the listener into the narrative. They are stories about us. The failures of their protagonists are our own failures. This is no less true with regard to the unmerciful servant. At a fundamental level, the unmerciful servant fails because he believes that his fellow servant is undeserving of his mercy while he is deserving of the king's mercy.

Martin Bordelon is a practicing Roman Catholic who resides with his wife and son in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he works as a network technician. He is also the author of the blog Love and Sedition (loveandsedition.wordpress.com).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

8.4—Fall 1995

The Demise of Biblical Preaching

Distortions of the Gospel and its Recovery by Donald G. Bloesch

more from the online archives

19.10—December 2006

Workers of Another World United

A Personal Commemoration of Poland’s Solidarity 25 Years Later by John Harmon McElroy

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor