Feature

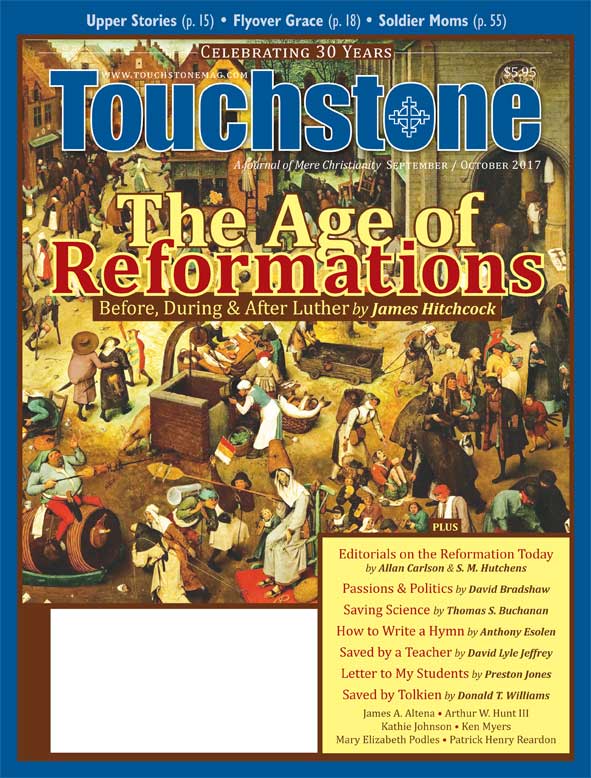

The Age of Reformations

The Critical History Before, During & After Martin Luther by James Hitchcock

Part 1: A Troubled Period

Movements once variously designated as the Christian Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation, the Protestant Revolt, the Catholic Reformation, and the Counter-Reformation are, from a historical point of view, perhaps now best understood as part of something that might be called the Age of Reformations—two centuries of both notorious corruption and genuine renewal.

It was one of the Catholic Church's most troubled periods, as the over-reaching papacy of the thirteenth century was brought low and entrapped in its own coils, providing little spiritual leadership.

The movement of the papacy from Rome to Avignon caused the popes to be seen merely as contestants in an international power struggle. But their eventual return to Rome provoked the even greater scandal of the Great Western Schism, when there were first two, then three, rival claimants to the papal office, a schism that was ended by the Council of Constance in 1415. Conciliarism—the claim that ultimate ecclesiastical authority resided in the general councils—was proposed as a guard against a corrupt papacy, but subsequent popes rejected it. After their return to Rome, the popes were obsessed with the Italian wars, and powerful families engaged in cutthroat competition for the papal office.

Demands for reform echoed continuously. The clergy were condemned for greed, lust, laziness, dishonesty, and other real or imagined sins. Monks and nuns were accused of violating their vows by fornication and living in quasi-luxury. Bishops were wealthy and politically powerful. Pluralism—holding more than one benefice at a time—and the absenteeism that necessarily accompanied it, were increasingly tolerated. Nepotism was also rife.

Most lay people did not, however, lose their faith. Traditional piety still had great power, and the invention of printing around 1450 allowed religious books of all kinds to be published.

Devotion to Christ in his Passion and to the Virgin Mary was pervasive, as was devotion to the Eucharist, although communion was received only occasionally. Devotion to the saints continued at the heart of popular piety, along with much credulity about the supernatural. Shrines were visited by large numbers of pilgrims. Preaching was highly valued, sometimes from outdoor pulpits. The deathbed was the crucial moment when the soul was suspended between salvation and damnation. Indulgences—applicable to both the living and the dead—could alleviate the sufferings of Purgatory.

Atmosphere of Anxiety

The Black Death of 1347–1349 was the greatest natural disaster in Western history, and partly because of it an atmosphere of spiritual anxiety, even of dread, hung over the age. Ritual flagellation was practiced by organized groups of lay people, who went in processions from town to town to expiate their sins. (Popes forbade the movement, which was treated by the Inquisition as a heresy.)

Possibly because of this anxiety, witchcraft, which had attracted relatively little attention in the Middle Ages, came under increasingly fanatical scrutiny from the late fifteenth to the late seventeenth centuries, proving to be an area of unhappy ecumenical agreement.

James Hitchcock is Professor emeritus of History at St. Louis University in St. Louis. He and his late wife Helen have four daughters. His most recent book is the two-volume work, The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life (Princeton University Press, 2004). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on protestant from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor