A Thousand Words

St. Luke the Evangelist

The Gospel Book of St. Augustine

Sometimes a work of art proves itself column-worthy for its place in the history of art, sometimes for its associations, and sometimes for its esthetic merit alone. Sometimes all three. Such is the Gospel Book of St. Augustine, a sixth-century manuscript now housed in the Parker Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, except when it travels to Canterbury to take part in the enthronement of a new archbishop.

Tradition says that this manuscript was one of those sent by Pope St. Gregory the Great with the Benedictine St. Augustine on his mission to the Anglo-Saxons. Scholarly evidence does nothing to contradict the tradition: the text and illustrations seem to have originated in sixth-century Italy, making this perhaps the oldest Latin Gospel still in existence. An illustrated Gospel was also a logical choice to send. Gregory famously defended the worthiness of religious art, asserting that pictures were effective in transmitting the faith to nonbelievers and in explaining Scripture to the unlettered—just what Augustine might have needed in Kent.

The manuscript is not lavishly illustrated, nor technically "illuminated," as there is no gold. Nor are there any decorated initials. Only two full-page illustrations (approx. 8.5" x 11") remain, though close examination and collation suggest there were more. One is a page of scenes from the Passion, and the other is the portrait of St. Luke shown here.

The Illustration

St. Luke is a white-bearded figure seated on a cushioned marble chair, legs crossed, in a pose like a Roman Senator or a Classical philosopher. One hand displays his book, and the other supports his chin in a meditative, listening pose as he gazes into the distance. He is not writing, as he might be in a Greek manuscript; his book was originally blank, as if he were awaiting the voice of inspiration. (A later hand has written in the words, "There was a man sent from God," from John's Gospel but referring to the opening story of Luke's, the birth of John the Baptist. A lot can happen to a manuscript in 1,500 years.)

Above Luke's head is a lintel inscribed with a line from the fifth-century Carmen Paschale, identifying St. Luke with the winged ox, one of the four creatures of the vision of Ezekiel. Above that is the ox himself, in a kind of apse or tympanum, hooves elegantly poised and engaging the viewer eye to eye. On either side of the Evangelist, pairs of red and bluish marble columns frame twelve small scenes from the Gospel, some of which are unique to Luke. They are arranged like a fresco cycle on a church wall, and it has been conjectured that they might reflect the frescoes that once adorned Rome's Santa Maria Antiqua, now destroyed. It is not easy to identify all the scenes with ease: they have been glossed in the margin, not always convincingly, in an Anglo-Saxon hand.

Unifying the whole of the page is an organizing Classical architecture. The opening in which St. Luke sits, the tympanum above, and the flanking walls and columns suggest the scenae frons of the Roman theater, the fixed center meant to focus an audience's attention. We have mentioned St. Luke's philosopher pose; note also that the Christ of the side scenes is the Classical clean-shaven youth and not the bearded Semite who suddenly appears almost universally in the late sixth century. The unifying color scheme, a subdued palette of grayish blues, warm yellows, and reddish-browns, thinly painted, recalls the airy frescoes of Late Antiquity. This could never be mistaken for a Classical work, yet the continual harking back to Classical forms and themes is one polarity in the pendulum swings of Western art, and is worth noting in the period of Gregory the Great.

The Text

The text of the Gospel Book is written in a small, neat Classical script called "uncial," as clear and readable to the modern eye as it was in its day. In the Classical fashion, the words are not separated, but they are arranged in short segments in the arrangement called "cola et commata," roughly "by clauses and pauses," so they can easily be read aloud. Christopher de Hamel, in his delightful book Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, describes it this way:

[T]he first line of each sentence fills the width of the column, and any second or subsequent lines are written in shorter length. . . . Each unit is probably what a person would read and speak aloud in a single breath. Thus Matthew opens, 'The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, son of David, son of Abraham', pause, take a breath, glance down silently at the next phrase, 'Abraham begat Isaac', another intake of breath, look back again at the text, 'And Isaac begat Jacob [and] Jacob begat Judah and his brothers', breathe again, and so on.

Mary Elizabeth Podles is the retired curator of Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. She is the author of A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity (St. James Press, 2023). She and her husband Leon, a Touchstone senior editor, have six children and live in Baltimore, Maryland. She is a contributing editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on art from the online archives

more from the online archives

35.4—Jul/Aug 2022

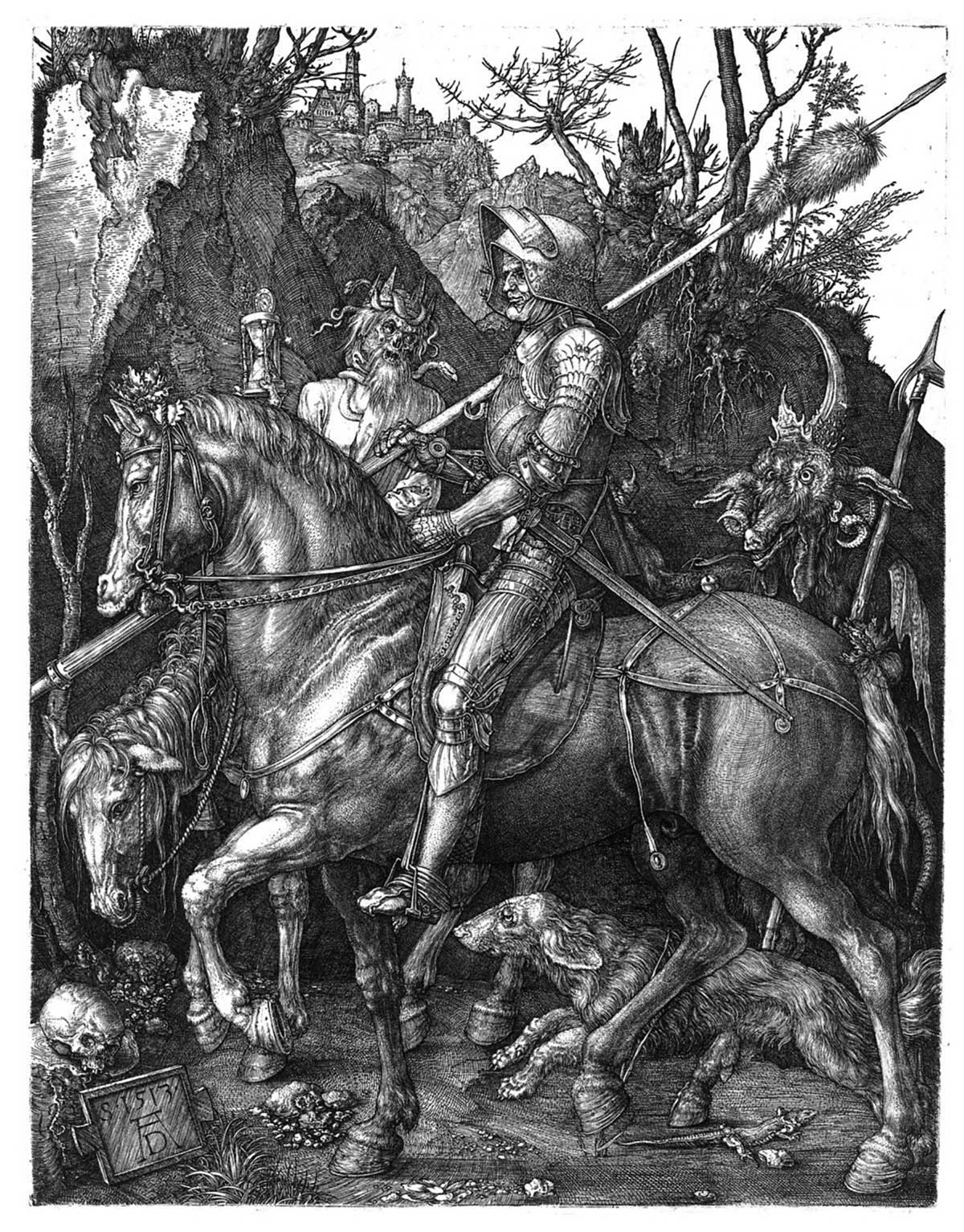

The Death Rattle of a Tradition

Contemporary Catholic Thinking on the Question of War by Andrew Latham

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor