Feature

We Are Not Our Own

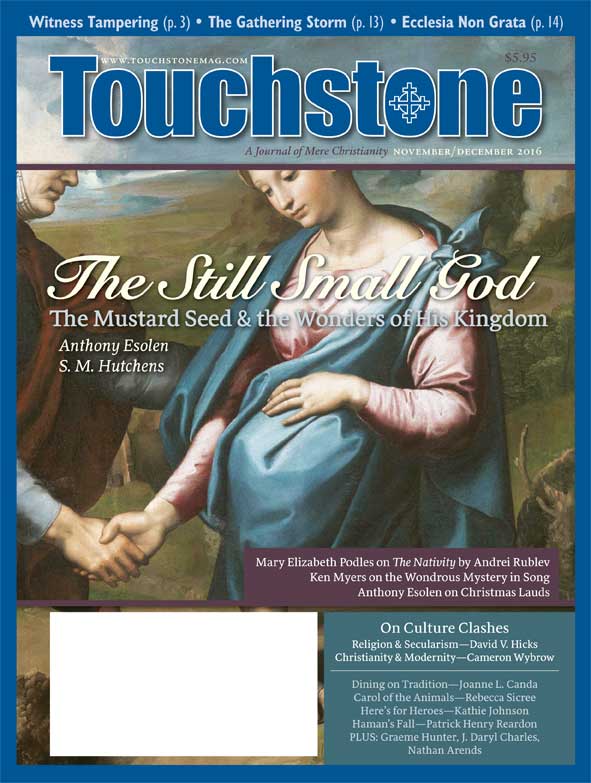

George Parkin Grant on the Deep & Abiding Tension Between Christianity & Modernity

Students, especially the most serious ones, often arrive at the university with high expectations. They imagine a place filled with professors who are masters in their chosen fields, repositories of a vast store of general knowledge, spellbinding speakers, cultured in works of art and literature, examples of great moral integrity, devoted to their students, and most of all, possessors of deep philosophical or even spiritual wisdom. Sadly, the real university professor is often a disappointment. Most professors are tolerably good specialists, but not particularly learned outside of their specialty, not particularly inspiring teachers, not particularly cultured, not particularly good as moral role models, and not particularly wise.

Why do so few live up to the expectations of the idealistic first-year student? The reasons are many. First, our culture tends to divorce knowledge from virtue. Second, the specialist structure of the modern university works against the intellectual formation of scholars with truly comprehensive minds, and should such scholars emerge by accident from the system, it works against the possibility of their being hired. Third, the publish-or-perish atmosphere of the university encourages the production of copious but shallow writing and thinking. For these and other reasons, the teacher who is deep and broad, humane and cultured, good and wise, is rare. Yet such teachers still exist, and where they exist, they command a following from the more thoughtful students and make an indelible impression upon them. One such teacher was the Canadian Christian philosopher George Parkin Grant (1918–1988).

Grant deserves to be better known to readers outside Canada, for he was a profound Christian philosopher of the public square. His writings, the result of deep philosophical and spiritual reflection, engage critically with the foundational affirmations of the modern secular world. From that engagement emerges a daunting picture of the tensions that exist between technological society and any form of conservatism, political or theological. The 2009 publication, by the University of Toronto Press, of the fourth and final volume of Grant's collected works, to which the page numbers herein refer, provides a natural opportunity to introduce him to those who are wrestling with the question of how, in a dynamic technological society, one can maintain both traditional faith and traditional conceptions of the ethical and political good.

Early Life & Conversion

Grant was the product of a British-Canadian system of education that is now defunct. With its emphasis on British and European history and culture, ancient and modern languages, the classics of English literature, and Christian religion, it sought to initiate the student into the great tradition of discourse which was Western civilization. Grant, as the scion of an educated, upper-class family in Toronto, began to learn this tradition at Upper Canada College, a prestigious private school in Toronto. Later, having acquired a degree in history from Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, he went off to Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship to study law, intending, upon his return to Canada, to take his place among Canada's social elite. The Second World War, however, shattered his career plans.

A pacifist at the beginning of the war, Grant volunteered as an Air Raid Precaution Officer on the London docks, and was witness to much death and suffering during the Battle of Britain. Later, having contracted tuberculosis, he went to work on a farm in Buckinghamshire. It was here that the defining event of his life occurred: "I went to work at five o'clock in the morning on a bicycle. I got off the bicycle to open a gate and when I got back on I accepted God" (358).

In order to understand the meaning of this statement, one has to understand Grant's religious background. Raised as a Presbyterian (his paternal grandfather had been a Presbyterian minister), Grant had been accustomed to churchgoing and of thinking of himself as Christian. But his Christianity had been a liberal, modern form of the faith, semi-secularized. As he put it, "I had been brought up in Toronto in a species of what I would call secular liberalism—by fine and well-educated people who found themselves in the destiny of not being able to see the Christianity of their pioneering ancestors as true" (358).

The idea of an actual experience of God was not part of the secularized Christianity in which Grant had been brought up. Thus, the event in Buckinghamshire was earth-shaking for him. In retrospect, he characterized it thus: "I would say that it was the recognition that I am not my own. In more academic terms, if modern liberalism is the affirmation that our essence is our freedom, then this experience was the denial of that definition, before the fact that we are not our own" (358).

The experience that God was real, and all that it implied, both for Grant personally (that his life was not his own) and for modern civilization (the horrors of which Grant had witnessed firsthand during the Blitz), reshaped Grant's life plan. When he returned to Oxford after the war, in 1945, he departed from the upper-class Toronto script for success, abandoning the study of law for the study of philosophy. For the rest of his life he would attempt to articulate a rational understanding of his Christian faith alongside an unsentimental analysis of modernity. As time went on, he would articulate the relationship between Christianity and modernity in terms of a deep and abiding tension, in which the modern claim that human beings are fitted for freedom, creativity, and autonomy was pitted against the ancient assertion that human beings were fitted for obedience, humility, and the practice of love and justice. Out of this tension sprang a form of philosophical writing which was unusually urgent and vigorous, and not infrequently expressed in a poetic prose of great beauty.

Philosopher & Teacher

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on biographical from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor