View

The True Atheist Myth

Jordan Bissell on Past & Present Atheism & the Invention of Happiness

In a review of Alister McGrath's recent book, The Big Question, Barbara King, a professor of anthropology at the College of William and Mary, takes issue with McGrath's characterization of atheism as lacking the meaning which, McGrath contends, can be found in a religious, and specifically Christian, worldview. That the philosophical implications of atheism should doom the atheist to an arid and desolate existence, King contends, is an unkillable myth: a shibboleth of the faithful as buoyant but as false as the contention that Darwin experienced a deathbed conversion. King ends her article by wondering, "How to make this unkillable myth about atheism into a moribund myth?"

But at least part of the reason this myth about atheists remains unkillable is the fact that so many atheists themselves have espoused it. Indeed, if we tour the last three centuries of pronouncements on the question of meaning, we discover just how much the lungs of atheists have given wind to these sails.

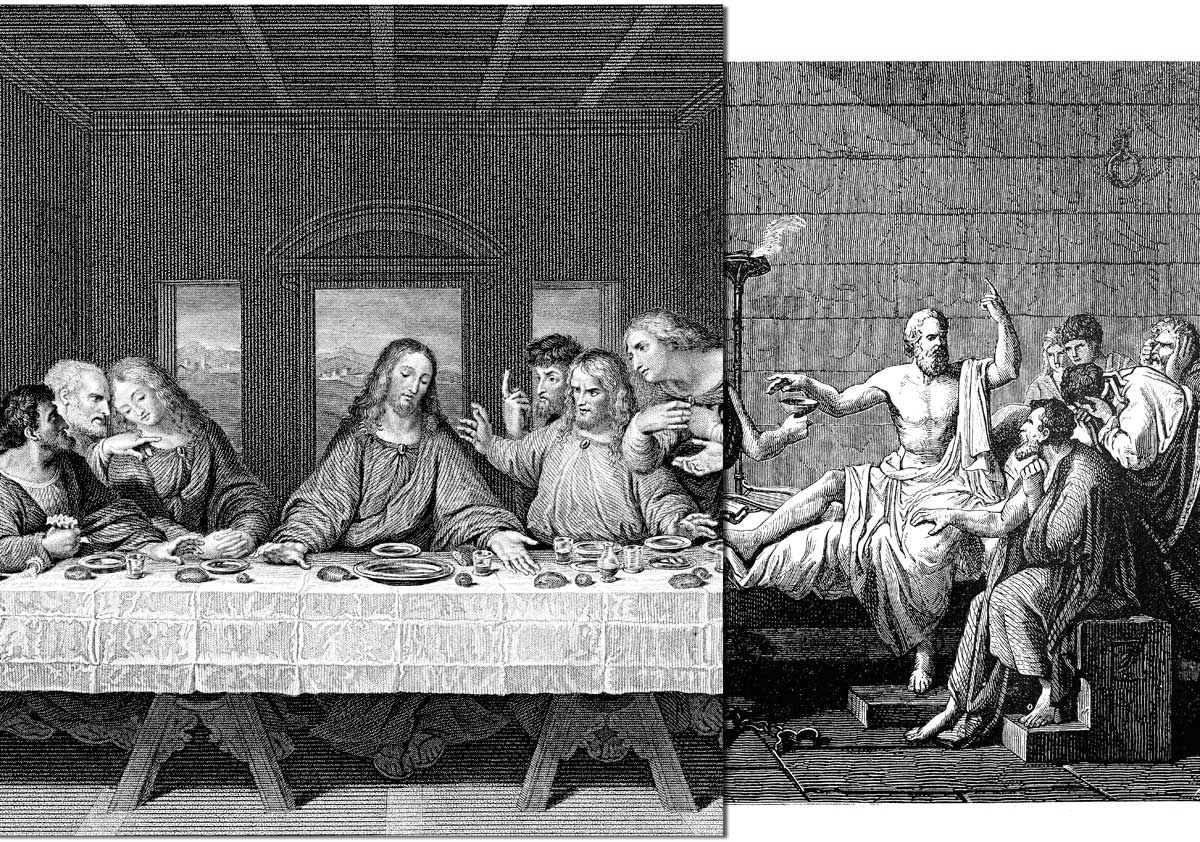

The Foundations of Despair

For instance, in the nineteenth century, writing in The Will to Power, Nietzsche argued that we would have to come to terms with "the belief in the absolute immorality of nature and in the utter purposelessness and meaninglessness of our psychologically necessary human impulses and affections." In speaking of the immorality of nature, Nietzsche was only echoing in a more prosaic way what the Marquis de Sade had said a century earlier: "Nature, averse to crime? I tell you that nature lives and breathes by it, hungers at all her pores for bloodshed, yearns with all her heart for the furtherance of cruelty."

In the last century, Jean-Paul Sartre famously declared that "Man is a useless passion," and in Existentialism Is a Humanism he explicitly rejects the idea that secular morality, untethered from religion and God, could enjoin on men the same old moral maxims, such as to be honest and not to lie. Instead, Sartre takes the view of Dostoevsky, approvingly citing his remark that if there is no God, anything is permissible, and commenting, "There can no longer be any good a priori. . . . Everything is indeed permitted if God does not exist, and man is in consequence forlorn." For Sartre, the nothingness that must envelop us at death is present like a worm in the apple of our everyday lives.

Bertrand Russell wrote in A Free Man's Worship that our hopes, loves, and beliefs are but the "outcome of an accidental collocation of atoms." "Even more purposeless, more void of meaning," he asserted, "is the world which Science presents for our belief," which must lead us to organize society "on the firm foundation of unyielding despair." In The Problem of Pain, C. S. Lewis, perhaps attempting to outdo Russell's bleak portrait of human life, summarized his own view as an atheist thus: "All stories will come to nothing: all life will turn out in the end to have been a transitory and senseless contortion upon the idiotic face of infinite matter." As a young man, Lewis, like Russell, took it for granted that this was the way things were. This absurdist view of the world led Albert Camus to posit that the first question of philosophy is whether or not one ought to commit suicide.

Senseless Inquiry

The contemporary face of atheism does not look much different. Richard Dawkins writes in River Out of Eden that "we cannot admit that things might be neither good nor evil, neither cruel nor kind, but simply callous—indifferent to all suffering, lacking all purpose." Ditto Steven Weinberg, whose now famous remark that "the more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless" barely pops the cork off the bottle of contemporary atheists who hold a similar view.

Many, like Dawkins in his debate with Cardinal George Pell, bristle at the notion that it makes any sense at all even to inquire into life's meaning. Such an attitude comports well with remarks made by Freud in a private letter to Marie Bonaparte, who said that the moment one begins to question the meaning or value of life, "he is sick, since objectively neither has any existence."

Jordan Bissell holds an M.A. in Religious Studies from the University of South Carolina. He is a former Benedictine novice, and currently works at Indiana University as an academic advisor. His writing has appeared at The Catholic Thing.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on philosophy from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor