Forum: Response

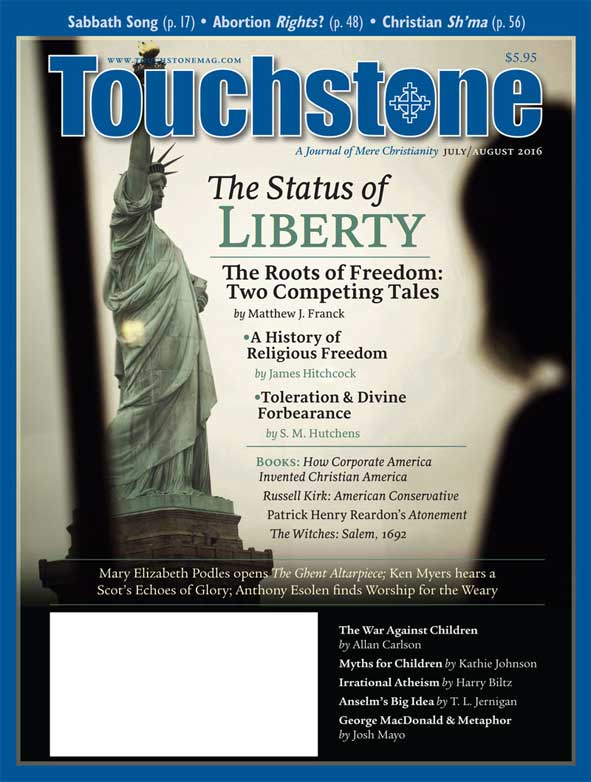

A History of Religious Freedom

Prior to Constantine, coercion in matters of religion was of course unthinkable to Christians, who were themselves the chief victims of such coercion. But leading theologians—Origen, Cyprian, Lactantius—did not offer a merely prudential argument. They affirmed the spiritual nature of a faith that was false if it was not freely chosen.

At the same time, the strongest possible distinction was made between coercion and doctrinal indifference. Already in the New Testament, Christians were told to shun those who denied the faith, and heresy was condemned as the gravest harm to that faith.

Given this distinction, coercion was essentially a political rather than a religious issue—how much did heresy damage the civil order, and what measures were justified to control it?

The first imposition of the death penalty for heresy was on the Spanish bishop Priscillian (385), who was accused by some of his fellow bishops of harboring Gnostic beliefs and being a sorcerer, which under Roman law was a capital offense. But his story is a very tangled one, and civil authorities played a major role in his execution. Ambrose, Martin of Tours, and others condemned the proceedings as a scandalous departure from Christian practice, and some of Priscillian's episcopal accusers were forced to resign

their sees.

Augustine, after agonized meditation, reluctantly accepted coercion in matters of religion because some of the Donatists of North Africa had become a violent sect, armed bands that raided the churches of the orthodox and slaughtered people whom they despised as traitors to the faith. The civil authorities regarded them as criminals who required severe punishment, and Augustine justified such action not because the state had a right to intervene but because the Church had the right to make use of worldly power to achieve its spiritual ends.

Augustine cited the parable of the man who gave a banquet as justification for this coercion, and—momentously—the host's final command to "make them come in" began to echo down the centuries. Augustine speculated that, while coerced faith was not faith at all, the descendants of those coerced might receive true faith. (Augustine's other major opponents—the Pelagians—were not physically coerced but were subjected to spiritual penalties.)

Charlemagne to Bernard

The legitimacy of coercion was accepted only very slowly. Pope Gregory the Great (c. 600) condemned forced conversions. But when Charlemagne (c. 800) brought the Saxons under his control, he ordered them to become Christians, and when he learned that his commands were being disregarded, he slaughtered a reported 4,500 people, despite the objections of his monk-advisor Alcuin of York.

Here again politics was as important as religion. Charlemagne saw the Saxons' acceptance of his religion as a necessary part of their submission to his rule, thereby making their infidelity a form of rebellion. (During the Eucharistic controversies in the century after Charlemagne, only spiritual penalties were imposed on accused heretics.)

James Hitchcock is Professor emeritus of History at St. Louis University in St. Louis. He and his late wife Helen have four daughters. His most recent book is the two-volume work, The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life (Princeton University Press, 2004). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Religious Liberty from the online archives

24.6—Nov/Dec 2011

Liberty, Conscience & Autonomy

How the Culture War of the Roaring Twenties Set the Stage for Today’s Catholic & Evangelical Alliance by Barry Hankins

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor