A Thousand Words

As the Old Sing,

So Pipe the Young

by Jan Steen

by Mary Elizabeth Podles

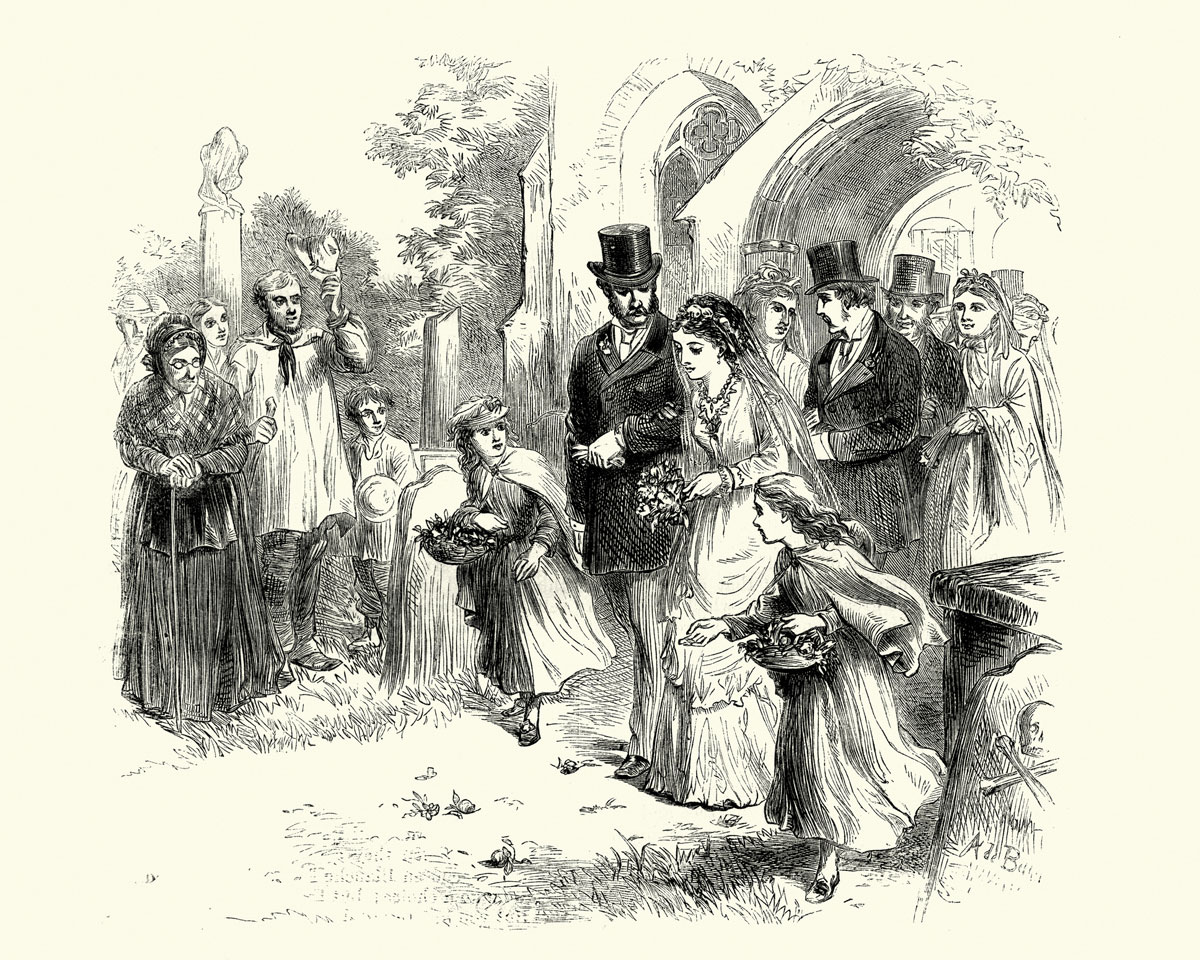

Jan Steen's 1663 painting of family merriment is a feast for all the senses. We can taste the oysters, fruit, and wine; smell the freshly peeled lemon and the pipe smoke; feel the Persian carpet, the wealthy wife's silks, furs, and velvet, and her dog's shiny coat; hear the old woman singing and the dulcet accompaniment of the bagpipes—all spread like a feast for the eyes, a theater piece in a shallow, stage-like space. In the largely Protestant Holland of the time, painters turned from specifically religious subject matter to more secular themes: landscape, portrait, still life, and genre scenes like this one taken from daily life.

As the Old Sing, So Pipe the Young

Like anything, subject matter goes in and out of fashion according to the times. Scenes like these enjoyed an uptick in popularity in the nineteenth century, since, like those of the Impressionists, they gave the stuff of ordinary doings the weight of high art. In the twenty-first century, we tend to look at genre scenes like these as historical records, video stills freezing a moment in seventeenth-century real time. For example, in his book Vermeer's Hat, Timothy Brook calls upon various props within Vermeer's popular paintings to open doors onto aspects of Dutch history that might otherwise have made dull reading.

Good & Bad Examples

Art historians shake their heads. Literal readings are seldom enough. In their own time, seventeenth-century paintings even of worldly subjects were generally meant to point to a moral truth, often in a veiled way. Or, as in Steen's painting, a not so veiled way: the song sheet from which the grandmother is singing is clearly titled, "Soo voer gesongen, soo na gepepen," roughly, "As the old sing, so pipe the young." This painting is about setting a good example. What children see is what they will parrot. There is even a parrot at the upper left to remind us. And at the upper right, a boy plays the bagpipes along with his grandmother's song, punning directly on the motto's verb, "to pipe."

A similar pun, and a bad example, is going on just below the boy, as the father of this family laughingly offers a little boy a puff on his pipe. In a bit of self-deprecating humor, Jan Steen has made this bad father a self-portrait, and the laughing woman topping up her wineglass is his wife Margriet van Goyen. There is evidence that a certain amount of wine has already been consumed: the rather large carboy on the windowsill is half empty, there is a jug at the wife's feet, and a servant holds another aloft to give her a refill. There is also beer on offer at the window.

Furthermore, the wife's inhibitions, as well as her bodice, seem to be loosened. The oysters set at her table were thought to be an aphrodisiac; the birds above her head may be another pun (the verb "to bird" was contemporary slang for sexual activity); the lapdog could connote sensuality—and then there is the footwarmer.

Emblematic Images

In the seventeenth century, collections of improving moral maxims called emblem books were a popular literary genre. They consisted of a series of emblematic images, often of simple household objects, each accompanied by a clever rhyme pointing to a moral lesson. In the best known of these emblem books, Roemer Visscher's Sinnepoppen, the footwarmer is called "The Ladies' Darling," and the accompanying poem comments obliquely on the dangers of this item. The connotations hardly need to be spelled out: the footwarmer contains a pan of hot coals that release warm air through the holes on the top, thus sending a waft of warm air up a lady's skirts (but a wayward spark could cause a disaster). And so, in a painting, a Dutch artist could include an emblematic object like a footwarmer and leave its meaning ambiguous. It could imply sexual excess or misconduct, or, if it is set aside or used with caution, it could be an emblem of chastity.

But to continue with our cast of characters: to the lady's left is an old man, presumably the singing woman's husband and the grandfather of the children present. He is wearing a paternity cap, the hat a new father wore between his child's birth and its baptism. The child is to his left, in the arms of a nurse, and presumably this feast is the baby's christening party. The father has taken off the cap and the grandfather has put it on. Obviously he considers it a great joke to be the patriarch of such an unruly pagan brood.

More to the Picture

Jan Steen's pictures of such scenes of merriment—baptisms, Epiphany feasts, St. Nicholas' Day, and the like—were extremely well-received, and to this day among the Dutch, the phrase "a Jan Steen household" means a chaotic, madcap, and messy establishment.

Mary Elizabeth Podles is the retired curator of Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. She is the author of A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity (St. James Press, 2023). She and her husband Leon, a Touchstone senior editor, have six children and live in Baltimore, Maryland. She is a contributing editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on art from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor