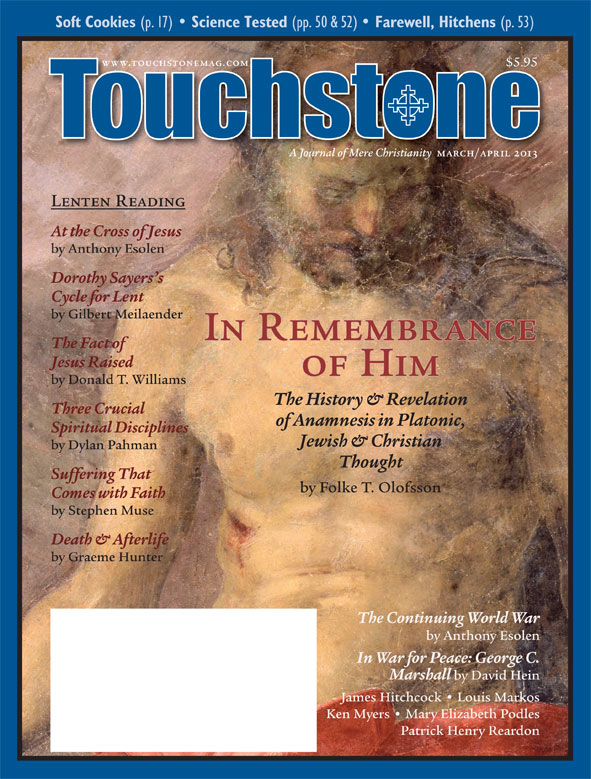

All This in Remembrance

The History & Revelation of Anamnesis in Platonic, Jewish & Christian Thought

by Folke T. Olofsson

Both Luke and Paul use anamnesis ("in remembrance") in their accounts of the Last Supper. The English translation does not do this rich word justice.

The ancient Greeks were quite familiar with and used this word. In one of Plato's dialogues, Meno, he lets his mouthpiece, Socrates, present the theory of anamnesis as a response to what has become known as the sophistic paradox, or the paradox of knowledge. Meno poses the question of how knowledge can be gained at all:

How will you look for something when you don't in the least know what it is? How on earth are you going to set up something you do not know as the object of your search? To put it in another way, even if you came right up against it, how will you know that what you have found is the thing you didn't know? (Meno, 80D, from Edith Hamilton and Huntingdon Cairns, eds., Collected Dialogues of Plato [CDP], trans. W. K. C. Guthrie [Princeton Univ. Press, 1961], p. 363.)

Since sure knowledge, then, seems to be impossible, is the search for knowledge futile? Socrates answers objections like these by referring to anamnesis, the idea of recollection. The human soul, he says, "since it is immortal and has been born many times, and has seen all things both here and in the other world, has learned everything that is. So we need not be surprised if it can recall the knowledge of virtue or anything else which, as we see, it once possessed" (Meno, 81C, CDP). What we call "learning something" is essentially a recollection of what the soul already knows, and the teacher is more like a midwife. Why have we forgotten? The trauma of birth makes the soul forget what is known, but it is all there within us: anamnesis.

In the dialogue Phaedo, Plato further develops his theory of recollection and combines it with his idea of forms. The soul is preexistent, eternal, and immortal; through anamnesis man can gain knowledge. The way through anamnesis to knowledge is by disregarding the body and purifying oneself from the bodily senses. It is through this purification—katharsis—and through philosophical thinking (one is tempted to say, "pure reason") that man obtains knowledge.

But why is the soul immortal and what kind of knowledge does it obtain? The answer is that "the soul is immortal because it can perceive, have a share in truth, goodness, [and] beauty, which are eternal" (Introduction to Phaedo, CDP, p. 40). Through this participation, in which the soul has its identity, the knowledge it gains is a knowledge of the Absolute. In other words, "man can know God because he has in him something akin to the eternal which cannot die."

This knowledge or even participation in the Absolute does not, however, include man's total existence, since it excludes his body. It is a purely intellectual, spiritual thing, the immortality of the soul. Plato's view is, therefore, ahistorical. It is not concerned with what is going on in the "real world"—with things, physical connections, and historical events—because the "real world" is not the real world. The real world is the world of Forms, of the Absolutes.

The Jewish View

Zikkaron is the Hebrew word for the Greek anamnesis. The difference between the two conceptions can hardly be exaggerated: they represent two different worlds, two different modes of understanding human existence.

Folke T. Olofsson is docent of theological and ideological studies at Uppsala University, and is rector of Rasbo parish in the (Lutheran) Church of Sweden. He is a contributing editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on history from the online archives

14.6—July/August 2001

The Transformed Relics of the Fall

on the Fulfillment of History in Christ by Patrick Henry Reardon

15.6—July/August 2002

Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World

The Shape of Divine Providence & Human History by James Hitchcock

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor