Introduction

Incomprehensible Freedom

A few years before his death, Cardinal Francis George, commented that "in the United States, individualism as an ideology is so closely associated with the creativity and personal freedom that the Gospel's injunction to surrender oneself to Christ and to others in order to be free has become largely incomprehensible." [emphasis mine]

Imagine Cardinal George trying to discuss freedom with a libertarian who understands freedom as a sort of protective ring around each individual within which he can act in a way that pleases him most. Meanwhile, for Cardinal George and for Christians generally, that so-called protective ring is nothing but a realm of unchecked bondage to fallen desires, advertising, or what have you.

We have all seen debates where a Christian says something like "there is no freedom outside of Jesus Christ," true words which mean nothing to the non-Christian. Meanwhile, the libertarian may answer with something like "I want to be free to bring happiness to my family in the best way I know how." To ask who won the debate is to ask a rhetorical question.

Sooner or later, all Christians, and especially all American Christians, must wrestle with the questions of what freedom is, and what is it for. As Cardinal George said, our answers, if they are true, will probably be incomprehensible to non-Christians (and to many Christians as well).

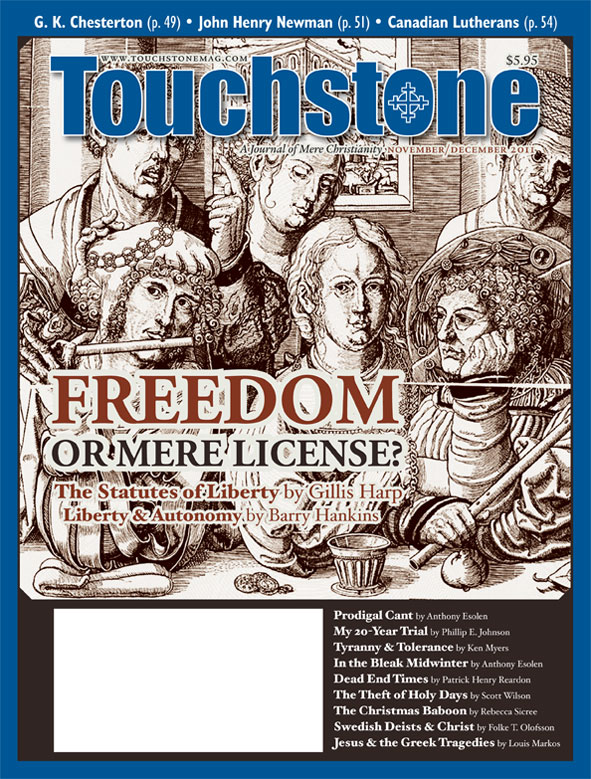

And yet, even if we can't explain Christian freedom, we can at least make clear that we are talking about something entirely different from the freedom to do as one wishes. The next time you find yourself in such a discussion, I think this article by Professor Gillis J. Harp of Grove City College from our Nov/Dec 2011 issue will serve you exceptionally well.

—Douglas Johnson, Executive Editor

(read more Editor's Picks)

Statutes of Liberty by Gillis J. Harp

View

Statutes of Liberty

Gillis Harp on the Tyranny of Modern Freedom versus the Freedom of Jesus

The 125th anniversary of Grove City College was marked by the publication of an institutional history entitled Freedom’s College. The title was appropriate given the college’s long-established defense of American political and economic freedoms. The title was also inspired by the famous Supreme Court case of the 1980s when the college defended her independence from federal interference.

It strikes me as very wise for a Christian college to enjoy a good deal of independence from intrusive state controls. The separation of church and state is one of the historical distinctives that helps account for the relative health and prosperity that Christian churches have enjoyed in the United States in contrast to the experience of Christianity in, say, Western Europe. This sort of freedom and other historic American political freedoms should definitely be celebrated and defended by Christians.

But I would like to address some problematic notions of freedom that have gained currency among American Christians, especially in recent decades. Some conservative Christians have, I fear, uncritically accepted ideas of personal and civil freedom that are at odds with traditional Christian teaching. Some have naively accepted what are essentially Enlightenment understandings of liberty that are at best in tension with what Scripture and Christian tradition teach.

First, I’d like to survey the sources of these popular views and clarify the problems with them. Next, I’ll describe a Christian perspective on this subject. And, finally, to conclude, I’ll try to offer a few practical suggestions about how to resist this tendency. My main point is a simple one: that for the Christian, freedom can never be asserted in an unqualified, absolute sense, without limits or some higher end in view. In other words, the Christian must always ask, freedom for what?

Undirected Freedom

For a long time, and especially since the Enlightenment, many in the West have defined freedom simply as the right to do as I choose, as long as I don’t hurt others. Note how this open-ended definition has no larger good or final goal in view. It is primarily negative, i.e., my freedom is defined as the freedom from external restraint or from imposed restrictions.

It is often argued that individuals should be left free to pursue their particular ends without reference to some larger social good. Indeed, some enthusiasts assert that there is actually no larger social good. They go as far as to assert that there is no such thing as society! For some, that’s just a meaningless abstraction. There are only individual goods, no general interest of the community in any organic or larger corporate sense.

Our self-centered consumerist society has latched onto this particular idea of freedom in recent decades. Of course, by doing so, it reduces our significant freedoms to trivial choices. I remember a promotional program that the convenience store Seven-Eleven ran back in the nineties. It was for their soda-fountain drinks. Big posters in red, white, and blue proclaimed: “Super Big-Gulp. America Loves the Freedom!” At the time, I wondered what foreign visitors would think about the American idea of liberty when it was reduced to being able to purchase a garbage-can-sized cup of Mountain Dew. Clearly, this is choice with no higher end in view, choice as an end in itself; choice reduced to just following my personal passion for soda or Slurpees.

William Cavanaugh, a theologian who teaches at St. Thomas University in Minnesota, addresses the question of this trivialized notion of freedom and how impoverished it is. He argues (drawing upon Aristotle and others) that this sort of freedom has no end; it is undirected freedom. Cavanaugh argues that for freedom to really constitute and create human freedom, there must be a telos, a goal or end in view. In his book Being Consumed: Economics and Christian Desire, he writes, “The absence of objective goods [that is, moral ends worth pursuing] does not free the individual, but leaves him or her subject to the arbitrary competition of wills.” It creates the sort of world vividly described by the inspired author of the Book of Judges: “In those days there was no king in Israel. Everyone did what was right in his own eyes” (Judges 21:25). Cavanaugh cites examples of areas in which such an extreme approach can actually produce what he calls “unfreedom.”

Continue Reading

Gillis J. Harp is Professor of History at Grove City College in Pennsylvania and the author of Brahmin Prophet: Phillips Brooks & the Path of Liberal Protestantism (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003). He and his family worship at Grace Anglican Church in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania.

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS

full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone

online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

24.6—Nov/Dec 2011

Liberty, Conscience & Autonomy

How the Culture War of the Roaring Twenties Set the Stage for Today’s Catholic & Evangelical Alliance by Barry Hankins

24.6—Nov/Dec 2011

Statutes of Liberty

on the Tyranny of Modern Freedom versus the Freedom of Jesus by Gillis J. Harp

more from the online archives

25.3—May/Jun 2012

The Soul of Liberty

Calls for Freedom, Democracy & Secularism End Up with None of the Above by Hunter Baker

21.4—May 2008

Attention Deficit

on the Absence That Ritalin Can’t

Cure by Bruce D. Woodall

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor

Support Touchstone

00