Feature

The French Connection

The Many Parallels Between France’s Revolution & Today’s Anti-Christian Secularism

Would-be Marxists of the 1960s debated whether American society was then in a “pre-revolutionary” situation; by the time the smoke cleared, the answer was obviously in the negative, in the way Marxists understood revolution. The lasting effects of the sixties were cultural rather than political and economic, which caused the self-defined radicals—blinded rather than enlightened by their Marxism—to be slow in seeing them. The radicals did not overthrow the capitalist system or establish “participatory democracy,” but they did succeed in inflicting deep wounds on the nation’s moral and religious fiber. The effects of any cultural revolution are long-term, and in some ways the United States today may be on the verge of carrying that revolution to its completion.

History may indeed be repeating itself but, as always, as theme and variations, not as simple restatement. The situation today resembles not Russia prior to 1917 but France prior to 1789, and the history of the Catholic Church in early modern times offers striking parallels to the present.

Attacks from Without

Contrary to stereotype, Europe in the eighteenth century was by no means an irreligious culture. Most people were believers, the level of religious practice was high, and it was unthinkable that by the end of the century the Catholic Church in France would be all but destroyed.

But, through the centuries, governments had come to assume that the needs of the state took precedence. Monarchs wanted a free hand in dealing with religion, and the government of France was at pains to protect the liberties of the Gallican Church—the independence of the French Church from Rome. The pent-up spiritual energies that exploded in France after 1600 caused Cardinal Armand de Richelieu, himself personally devout, to seek to curb the religious zeal of others “for reasons of state.”

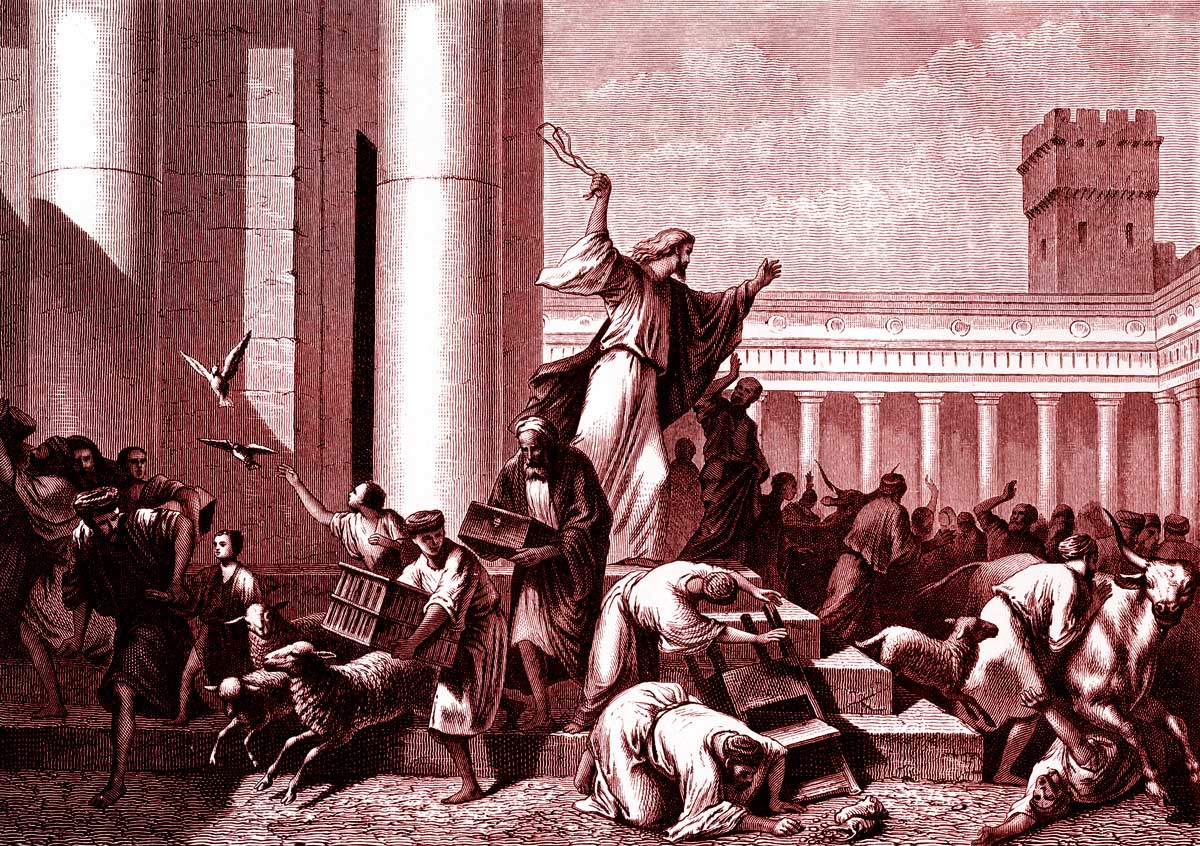

So religion began to be discredited, both legitimately and illegitimately, as a cause of division, persecution, and warfare. Although the early modern “religious wars” were not by any means solely about religion, the willingness of pious people to employ violence in support of their faith justified mistrust of their fervor, although that mistrust was also exploited for purposes that were sometimes even bloodier than the religious wars and more oppressive than the Inquisition.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries came to be called the Age of Reason not (as in the stereotypical account) because reason had previously been ignored but because during that period the ancient Christian synthesis between faith and reason was rejected and reason alone became the acceptable guide to truth. The Enlightenment unfolded into a stance of suspicion or outright animosity towards almost all existing beliefs and institutions, of which Christianity was the chief.

Also contrary to stereotype, the philosophes—the French intellectuals of the eighteenth century—sought not diversity of opinion but the replacement of one kind of intellectual unity by another. Feeling themselves to be in the ascendancy, they did not have to confront their opponents fairly, because, in their minds, certain ideas had been so thoroughly discredited as to be held only by the ignorant and deluded, and to take such ideas seriously would be to yield ground in the continuous war of ideas. Thus, perhaps the philosophes’ most effective weapon was the subtle censorship of fashion, the ability to make orthodoxy seem outmoded and ridiculous. Whatever else they were, the philosophes were masters of condescension and ridicule.

Alongside the condemnation of religion as a cause of hatred, a heightened historical consciousness—drawing on the work of Christians like Abbe Mabillon, Richard Simon, and Pierre Bayle—attempted to discredit Christianity in its very origins. Edward Gibbon endeavored to show in massive detail that the triumph of the Church had been the triumph of ignorance.

James Hitchcock is Professor emeritus of History at St. Louis University in St. Louis. He and his late wife Helen have four daughters. His most recent book is the two-volume work, The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life (Princeton University Press, 2004). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor