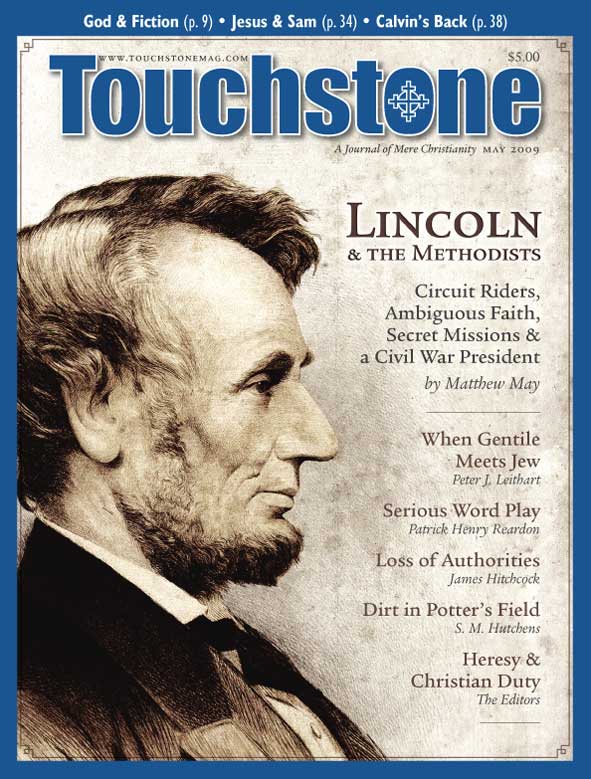

Lincoln & the Methodists

Circuit Riders, Secret Missions & the Trials of a Civil War President

by Matthew May

In Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead, the protagonist, Howard Roark, is told that though he does not believe in God, he is “a profoundly religious man, in your own way.” While he did believe in God, Abraham Lincoln, too, was a profoundly religious man, but he was so in his own inimitable style—so much so that close friends and associates considered him an agnostic. A friend of Lincoln’s who was a member of the bench spoke of Lincoln’s complete lack of taste for the rituals and ceremonies of traditional Christianity, and others at times even considered him an infidel.

While it is true that Lincoln outwardly disdained many of the trappings of organized religion, he was wisely never dismissive of organized religion itself. This was especially true of his dealings with Methodism. As we will see, despite the accusations and insinuations of infidelity leveled at him by one of the American West’s premier Methodists during his first run for national office, Lincoln found that the support and zeal of the Methodist Episcopal Church in his favor were vital to the successful prosecution of the Civil War and to the success of his presidency.

From Rowdy to Circuit Rider

In 1846, Lincoln clashed with a prominent representative of early American Methodism in the person of Peter Cartwright, a circuit rider who vied against Lincoln for a seat in the US House of Representatives from Illinois.

Peter Cartwright was born in Virginia in 1785 and raised in Logan County, Kentucky. The son of a Revolutionary War veteran, he was also, like Lincoln, a true child of the frontier. As he wrote in his memoirs, he was able to “turn in and split rails, go to the harvest field, reap, cradle, mow, plow or dig.”

Cartwright often witnessed worship services conducted right in the family cabin by a Methodist circuit rider—the Reverend John Lurton—when Lurton stopped in Logan County. The growth of Methodism on the American frontier led to the Western Conference being organized in 1801 at Cane Ridge; 2,000 people were converted to Methodism on and near the Cartwright property. Peter was not among those called; he was rambunctious and rebellious, interested in gambling on horses and cards while imbibing at a frightening pace.

A few years of such activity came down hard on Cartwright when, after a night of drunken debauchery at a wedding, he recognized his sloth and began to pray. As he later described it,

Divine light flashed all round me, unspeakable joy sprung up in my soul. I rose to my feet, opened my eyes, and it really seemed as if I was in heaven; the trees, the leaves on them, and everything seemed, and I really thought were, praising God.

Soon he was preaching as a “local,” and he was received into the ministry in 1804 and ordained as an elder in 1806 by Bishop Asbury. He rode the circuit in the Cumberland district until moving to Sangamon County, Illinois, in 1824.

Matthew May is the historian and archivist for the Detroit Conference of the United Methodist Church and co-editor of Michigan Methodism, Methodists, and More. He is a frequent contributor to the American Thinker website and has written for The American Spectator and Good News Magazine.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor