Feature

His Passion,

Our Choices

Matthew’s Trial of Jesus Is About More than Jesus by Patrick Henry Reardon

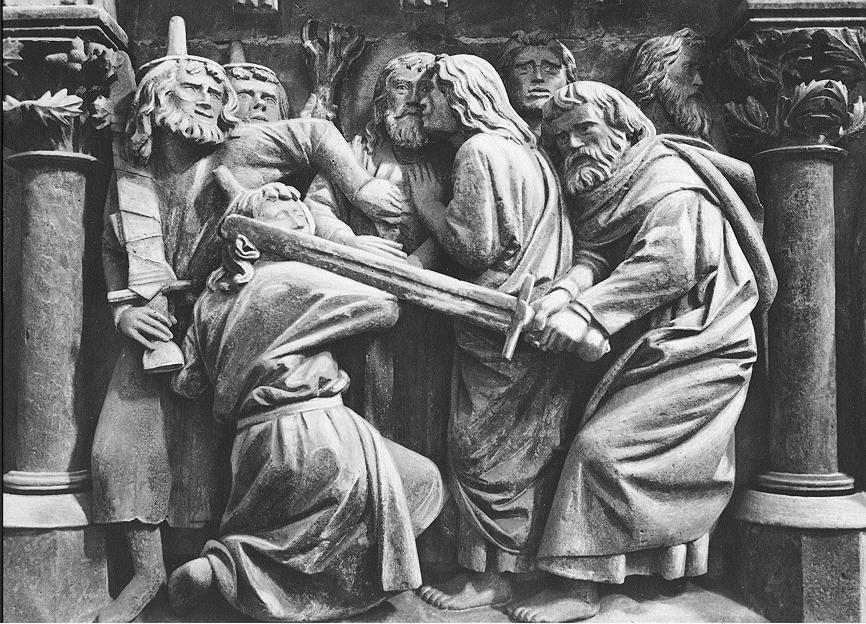

Although any day is a good occasion to read the Gospel accounts of the Lord’s Passion, it is hardly surprising that the ancient lectionaries of the Christian Church especially prescribe the solemn, public reading of these texts each spring—March or April—during Holy Week. An early witness to this prescription was Egeria, a nun from Gaul, who penned a priceless account of her travels in the Holy Land during the late fourth century, probably between 381 and 384.

Because she was fortunate to be present among the Christians in Jerusalem during Lent, Holy Week, and the Paschal season, Egeria’s account includes descriptions of the customs and rituals associated with the liturgical observance of those solemn seasons, including the public reading of the Passion narratives on Good Friday. This passage is worth quoting at length:

The entire time from the sixth to the ninth hour is occupied by public readings. They all concern the things that Jesus suffered; first they have the psalms on this theme, then the Apostolic Epistles and Acts which deal with it, and finally the passages from the Gospels. In this way they read the prophecies about what the Lord was to suffer, and then the Gospels about what he did suffer. Thus do they continue the readings and hymns from the sixth to the ninth hour, showing to all the people by the witness of the Gospels and the writings of the Apostles that the Lord actually suffered everything the prophets had foretold. They teach the people, then, for these three hours, that nothing which took place had not been foretold, and all that was foretold was completely fulfilled. Dispersed among these readings are prayers, all fitting to the day. It is impressive to see the way all the people are moved by these readings, and how they mourn. You could hardly believe how every single one of them weeps during those three hours, old and young together, because of the way the Lord suffered for us. (The Travels of Egeria)

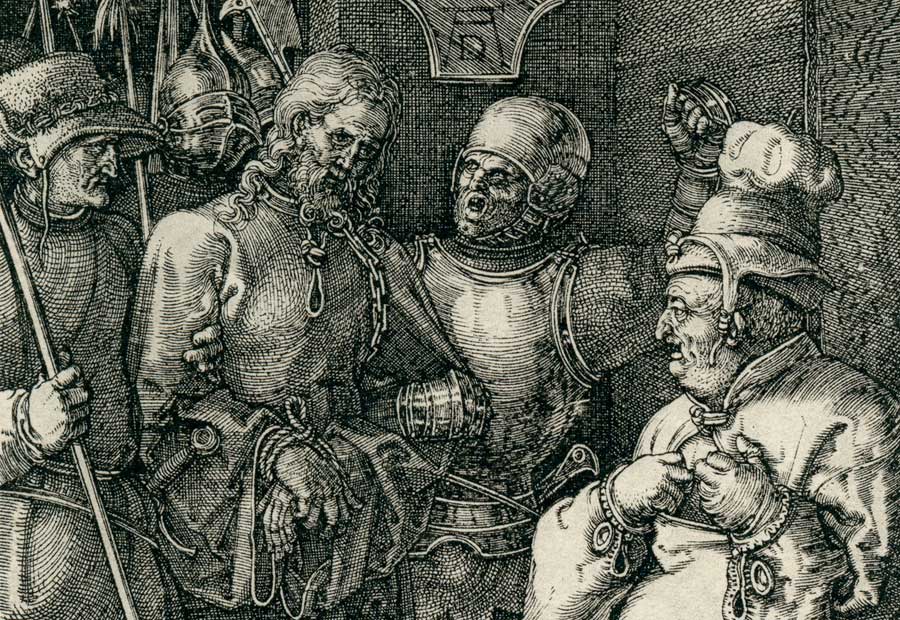

Jesus on Trial

Integral to the Gospel stories of the Passion are their records of the Lord’s two trials: the “Jewish” trial before the Sanhedrin and the “Roman” trial before Pontius Pilate. Jesus’ appearance before Pilate was ultimately included in the creedal narrative of the Church, including the Nicene Creed. This development apparently began early. If we bear in mind that a primitive word used for the baptismal creed was homologia (cf. 2 Cor. 9:13; Heb. 3:1; 4:14; 10:23), we perhaps detect in 1 Timothy 6:12–13 a first step toward the insertion of Jesus’ trial before Pilate into the Church’s confessional recitation:

Fight the good fight of faith, lay hold on eternal life, to which you were also called and have confessed [homologesas] the good confession [homologian] in the presence of many witnesses [martyron]. I urge you in the sight of God who gives life to all things, and before Christ Jesus who witnessed [martyresantos] the good confession [homologian] before Pontius Pilate. . . .

Although each of the four Gospels includes both of Jesus’ trials, the accounts differ quite a bit in the details. Sometimes these variations indicate source material peculiar to an individual Evangelist. For instance, it seems likely that Luke’s story of Jesus’ appearance before Herod (Luke 23:6–12) comes from his personal familiarity with Joanna, the wife of Chuza, who served in Herod’s court (8:3). In addition, only Luke includes the detail of the Lord’s turning to look at Peter after the third denial (22:61).

Likewise, only John tells of an interrogation of Jesus before Annas (18:12–13, 24), and only he seems familiar with the details of a conversation between Jesus and Pilate (John 18:34–37; 19:8–11). Again, Matthew alone appears to know that Pilate’s wife became interested in Jesus’ trial (27:19).

Sometimes, however, the differences between the four accounts of Jesus’ trials are better explained as particular features of the individual narrative preferences of the four authors. For instance, John provides not a single detail of Jesus’ interrogation by Caiaphas but says that Jesus was taken directly to Pontius Pilate in the morning (19:28). Thus, John records two distinct interrogations of Jesus by the Jewish leaders, the second ending in the morning.

Luke simplifies the narrative by saying the arrested Jesus was taken directly to the high priest’s presence (22:54). Although he tells us nothing about an interrogation until the morning (22:66), the details of that inquiry (22:67–71) closely resemble the interrogation before the Sanhedrin that Mark and Matthew portray as taking place during the night.

Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor emeritus of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church in Chicago, Illinois, and the author of numerous books, including, most recently, Out of Step with God: Orthodox Christian Reflections on the Book of Numbers (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2019).

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on bible from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor