XXX-

Communicated

Anthony Esolen on Why Pornography Is Not the Sin We Say It Is

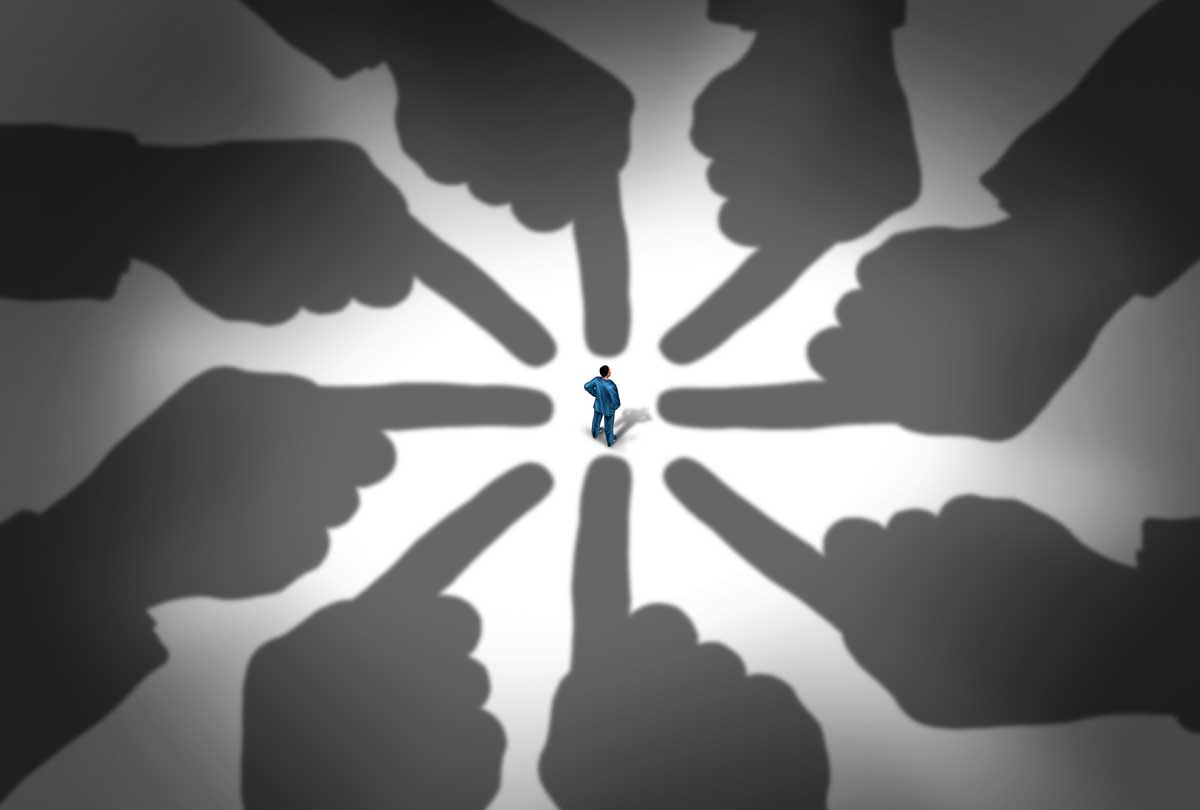

In any cultural war there are going to be large areas of agreement on all sides, and therefore plenty of opportunities for all sides to be inattentive and plain wrong. So with the sin of pornography. Most feminists decry it for casting women as mere objects of sexual pleasure, passive victims of a male gaze that is violent in imagination if not in its very essence. Social conservatives say much the same, and strain their gallantry by appearing to assert that every sin of lust involves this “objectification,” and that women are for the most part the hapless victims of that sin. Users of pornography, according to both camps, are ipso facto abusers of the women on parade.

That analysis has never persuaded me, not least because when a brick like “objectification” is tossed through my mental window, I figure somebody’s out to keep me from thinking quietly and sanely. I know that some users of porn are predatory and monstrous. But who are the other users, in the main?

Some are old men with nothing to do and no one to do it with. Others are pimply teenagers; not the rowdy footballers, but the oddballs, the outcasts. My students tell me that in every dormitory there’s one kid who has seven hundred skin flicks downloaded onto his computer—who stays shut in his room and never talks to girls. Others are men who have gambled or drunk their self-respect away, whom no decent woman would give a second look.

Still others, perhaps hundreds of thousands of them, are husbands who wish that a certain picture had never flashed across their computer screens, yet who continue to surf for the phantasms of sex, alienating themselves from their wives and their children, even from humanity, as they descend from the simply lewd into the horrible and bizarre, fully aware that they are doing so, yet always rationalizing once again, one last time. Some are even ministers of good will who have progressed imperceptibly from hearing about sin to haunting it.

These sinners surely are also victims of pornography, they whose frailty has been found out and exploited for money, or whose peace and health have been vitiated by the purveyors of smut. A drop of prussic acid can kill; a single pornographic image will persist, will form a fantasy memory hooked and barbed with the natural heroin of the brain, will reside in one’s soul, at best a cancer in permanent remission, at worst a gnawing parasite. How can we miss the violence here? Those who take the pictures, or who earn a lot of money making them, are also brutes. Violence does not always come at the end of a fist.

Brother Ass

But there are two deeper problems with that business about “objectification.” The first is simple. Where does it say that objectification is always wrong?

Consider what goes on when we engage in broad humor. A great deal of our laughter arises from the embarrassment of having to cart this body around, this Brother Ass, as St. Francis affectionately called it. There is a humility in physical humor: You allow yourself to be reduced to an object, a sack of potatoes, a lumpy thing with a wobbling center of gravity; Jackie Gleason like an elephant a-tiptoe, roaring and shaking his hammered thumb, or Lucille Ball wrestling with a contadina in a vat of grapes. Bawdy humor—which may be risky yet quite innocent too—also depends upon the humble object.

I think of the merriment of old-fashioned country songsters drunkenly hallooing and waking the poor bridegroom and bride in the middle of the night. Even in the playfulness of lovemaking there’s a delight not simply in the soul of one’s spouse, but in that good old lumpiness, the physicality, the downright tool-ishness. Innocent Adam and Eve surely would not always have thought about souls. Three cheers, then, for objects!

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on sex from the online archives

more from the online archives

19.10—December 2006

Workers of Another World United

A Personal Commemoration of Poland’s Solidarity 25 Years Later by John Harmon McElroy

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor