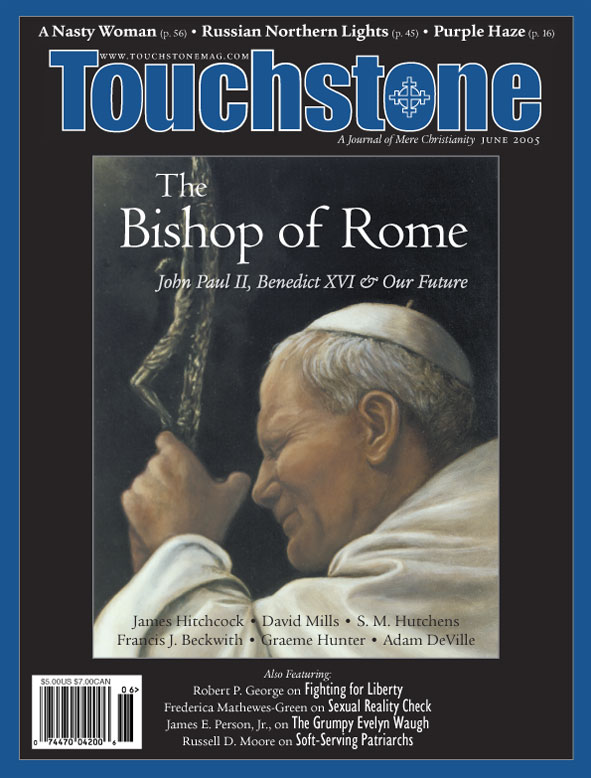

A Pope Alive

John Paul II’s Legacy Is More Than Most Realize

Given the spirit of the times, it was inevitable that Pope John Paul II would be judged in broadly ecumenical terms, not by his fidelity to the teachings of the church he headed but by his relationship both to other faiths and to the world at large, and that in those terms he would be judged a failure.

Conventional wisdom, as expressed in the media immediately following his death, did not usually put it quite so crudely, but alongside the mandatory encomia were polite (or not so polite) expressions of puzzlement at the pope’s “contradictions,” which finally came down to saying that, while he showed signs of becoming a good modern liberal, he somehow kept getting dragged back by the outmoded doctrines of his church. Even before the incense of the eulogies had dissipated, conventional wisdom had defined John Paul as a rather tragic figure in his inability to overcome the limitations of his personal history.

Much of the praise he was offered in death was irrelevant, even subtly demeaning to himself and his office, a litany of approved pseudo-virtues like warmth, informality, interest in others, good humor, and the common touch, qualities that are only related to Christian virtues in a highly diminished and reductionistic way and, insofar as they are laudable, are as applicable to bus drivers as they are to spiritual leaders. Most of the conventional praise ignored the question why there should even be a pope, or indeed any kind of church.

His “Contradictions”

Among the principal “contradictions” cited were his refusal to support Liberation Theology in Latin America while championing political freedom for his native Poland, his remaining “authoritarian” in almost all church matters while constantly insisting on human dignity and freedom, and his declaring that the church had no authority to ordain women to the priesthood while writing eloquently about the dignity of women. If editorial writers could see those inconsistencies so clearly, why could not the pope himself?

It was of course on sexual matters that John Paul attracted the most severe criticism. After Paul VI ignited a furor by his encyclical Humanae Vitae on birth control, knowing observers predicted that the doctrine would be found outdated, irrelevant, and widely rejected, and conveniently put on the shelf. Instead, John Paul chose to reiterate and develop it at every opportunity, and, as the frontiers of the sexual revolution expanded inexorably, as sexual hedonism became one of the few modern absolutes, he was the world’s greatest example of a genuine moral leader, someone still capable of saying “no.”

It was here also that the crippling limitations of the contemporary liberal mind became most apparent. Not only does conventional opinion reject orthodox Christian teaching about sexuality—teaching that is not just Catholic but “merely Christian”—it is incapable even of understanding it, so that John Paul had to be represented as merely a rule-bound ecclesiastical bureaucrat whose habitual nay-saying about sexual matters was forced on him by his own background and by the demands of his anachronistic office.

But John Paul’s meditations on human sexuality, in The Theology of the Body and elsewhere, are among the most sublime and far-reaching on the subject, not only in the history of Christianity but in the history of the entire human race, and they reveal not a hatred of the flesh but an almost extravagant respect for and wonder at human powers of creation. It was precisely because of that respect and wonder that John Paul so eloquently opposed the degradation and trivialization of those powers, not least by the modern world’s sundering them from the divine gift by which human beings participate in the miracle of creation itself.

The same consistency, based upon a depth of understanding beyond that of his critics, was true of all his “contradictions.” He supported democracy in Poland and elsewhere because he understood the dignity of man and the nature of the state, while opposing Liberation Theology because it distorted them to the harm (oppression and impoverishment) of those it wanted to help.

He opposed the ordination of women based both on the unbroken tradition of the church and on the Catholic understanding of the nuptial relationship of Christ and his church, in which the priest is the sacramental alter Christus. Characteristically, his critics would not even concede the relevance of authentically theological considerations; to them, the priesthood was merely a category of persons ripe for a wholly secular “affirmative action.”

James Hitchcock is Professor emeritus of History at St. Louis University in St. Louis. He and his late wife Helen have four daughters. His most recent book is the two-volume work, The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life (Princeton University Press, 2004). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

27.6—Nov/Dec 2014

Tales of Forbidden Stereotypes

Real-Life Men & Women & the Tragic Loss of Human Comedy by Anthony Esolen

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor