Feature

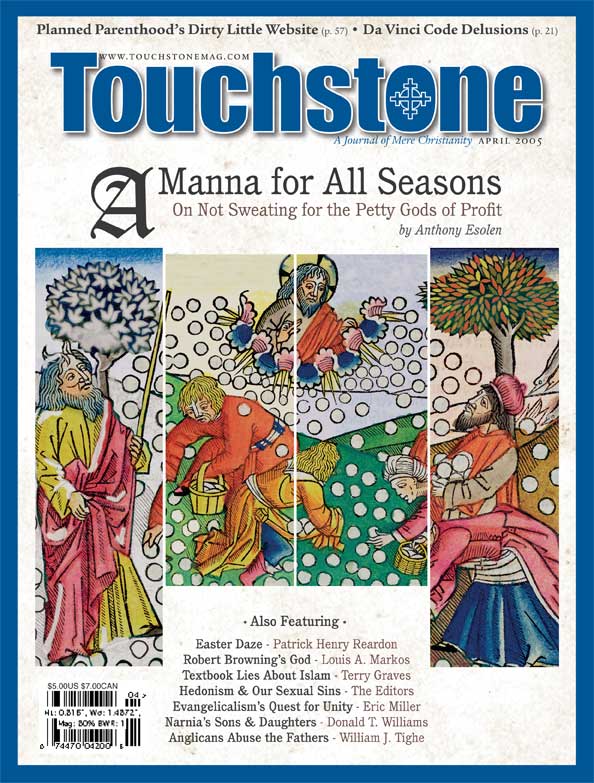

A Manna

for All Seasons

The Sabbath Challenge to the Petty Gods of Profit by Anthony Esolen

Tiriolo—Little Tyre, a trading fortress founded by the ever-busy Phoenicians 2,500 years ago—would now be no more than a sleepy village, were it not for the herds of goats that crowd its streets in the early morning once a week, and the Italians that crowd them at all other hours. People live well in Tiriolo, by their easy standards: They have good food and clean clothes, and it hardly ever rains. They work, but they don’t blow trumpets before them as they go. So it didn’t surprise me when my cousins—all of them grown up, with families—decided one fall afternoon, in the middle of the week, not to win bread but to hunt mushrooms.

Do not suppose we had baskets for assiduous gathering. The larger breeds of mushrooms, or funghi as the Italians so accurately call them, are shy, hiding under a fall of rotten leaves or in the wet crook of a half-dead oak. I might sit on a rock with a commanding view of the hill, combating a kind of spore-grown heresy with Francesco, un Testimonio di Gehova, and not catch a single mushroom battening on the wind.

The poisonous ones, I was told, are small and white, like those we eat in America. The really good ones, never to be purchased but only to be found, are rare behemoths, gaudy yellow and streaky red, sometimes capped like the umbrellas we know, sometimes just slabs of flabby tofu.

“ What’s that thing?” I asked, warily. But they cried out, “ Antonio, hai fatto bene!” It was a crimson blotch that might have corrupted the liver of St. Peter himself. That was the success of the day. For three hours we shouted and argued and complained about the walk back uphill, and all we had for profit were a half-dozen fungi.

The cousins were sweaty and happy, and I was shaking my head, American that I am, calculating how many hours the three men had taken from work, how much they could have earned, and how many baskets of spores they could have bought with the wages. But cousin Adriana cooked the mushrooms in our supper, and though they tasted like any mushrooms—that is, they savored of warm mold and woody mildew—they were good, no one died of liver failure, and the bank did not come to repossess the furniture.

The Week’s Purpose

It wasn’t the Sabbath, but it might as well have been. My cousins should have been working, I thought. Man is supposed to work—most of us have little choice in the matter, or loudly protest that we have no choice—except on the Sabbath, when we rest. But is that all there is to the relation between the days? Might there be something about the Sabbath that makes for good work the day before? Can you enjoy the Sabbath rest in the midst of labor on Thursday? What kind of hard Thursday work—or Thursday play—is like Sunday feasting? And what is the Thursday work for, if not ultimately for feasting?

My mind returns to that day in Little Tyre whenever I forget that the end of the week, the purpose of the week, is its return to the feast in the beginning. The Sabbath is a gift for man, says Jesus, and not man the sacrifice for a grim and demanding Sabbath. Profit be damned. When you forget the Sabbath, you mistake the other days, too. When you forget the feast, you forget what your work is for.

Before the Lord cast Adam and Eve out of Eden, where the fruit of the vine hung bountiful and free, he had a few words to say to the man about his labor: “Cursed is the ground for thy sake: in sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life: Thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to thee; and thou shalt eat the herb of the field; In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.”

Now, one way to fight a curse—our modern way, I think—is to deny that it is a curse. If God says we shall eat our bread in the sweat of our brows, then we make an idol of necessity and worship the sweat of our brows. We say, “How hard have we worked to build that granary and stuff it with grain!” We hug ourselves for our intelligence, our diligence, our seizing of the main chance, our scratching a bare meal out of the flinty soil, a meal that in our memory grows ever barer as we grow older and better satisfied with our victorious perseverance.

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor