Feature

Long Shadows of Eden

On Conservatism as Vexation, Vanity & Near Impossibility

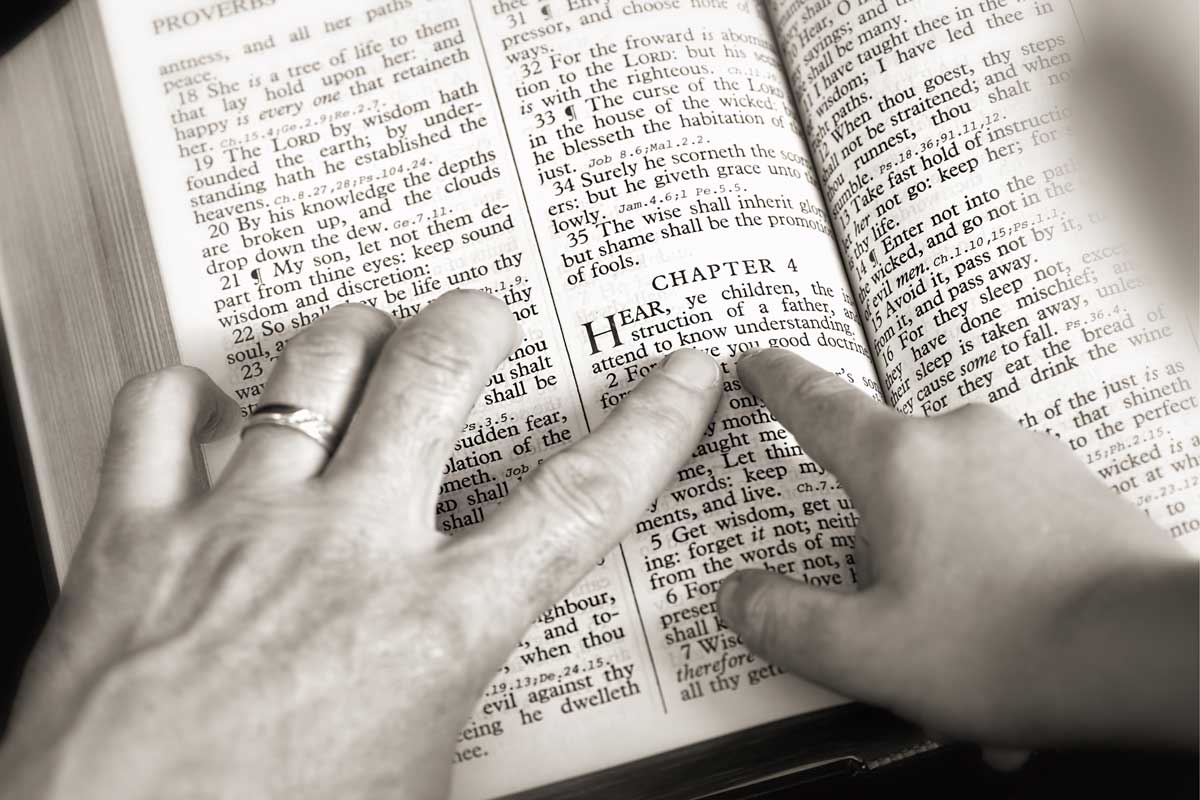

I would like to admit from the outset what in any case you will soon detect: I am no political scientist, nor a sociologist, nor a lexicographer. No form of expertise warrants my pontificating about what conservatism is and whether or not it is possible. This is therefore a personal meditation (perhaps something of a lament) by someone who would like to find an outlet for his conservative temperament, but now fears that such a wish may be what the Preacher describes as chasing the wind or, in an older translation, as vanity and vexation of spirit.

The problem I confront has not always existed in the acute form in which we encounter it today. The poet T. S. Eliot defined his own conservatism in lapidary terms. He described himself as Anglo-Catholic in religion, classicist in literature, and royalist in politics. But that position was already being held more for rhetorical effect than for practical purposes. Consider for a moment another poet not much later than Eliot who wore those same colors (at least in religion and politics). I speak of the former British poet-laureate, John Betjeman.

Betjeman’s conservatism expressed itself not only in politics and religion but also in a life-long dedication to preserving English country life. His writings on rural life and architecture have implanted in the minds of more than one generation of Englishmen and tourists a poignant and powerful idea of what is often called “Betjeman’s England.” Think of melancholy churchyards, verdant meadows, and unspoiled villages.

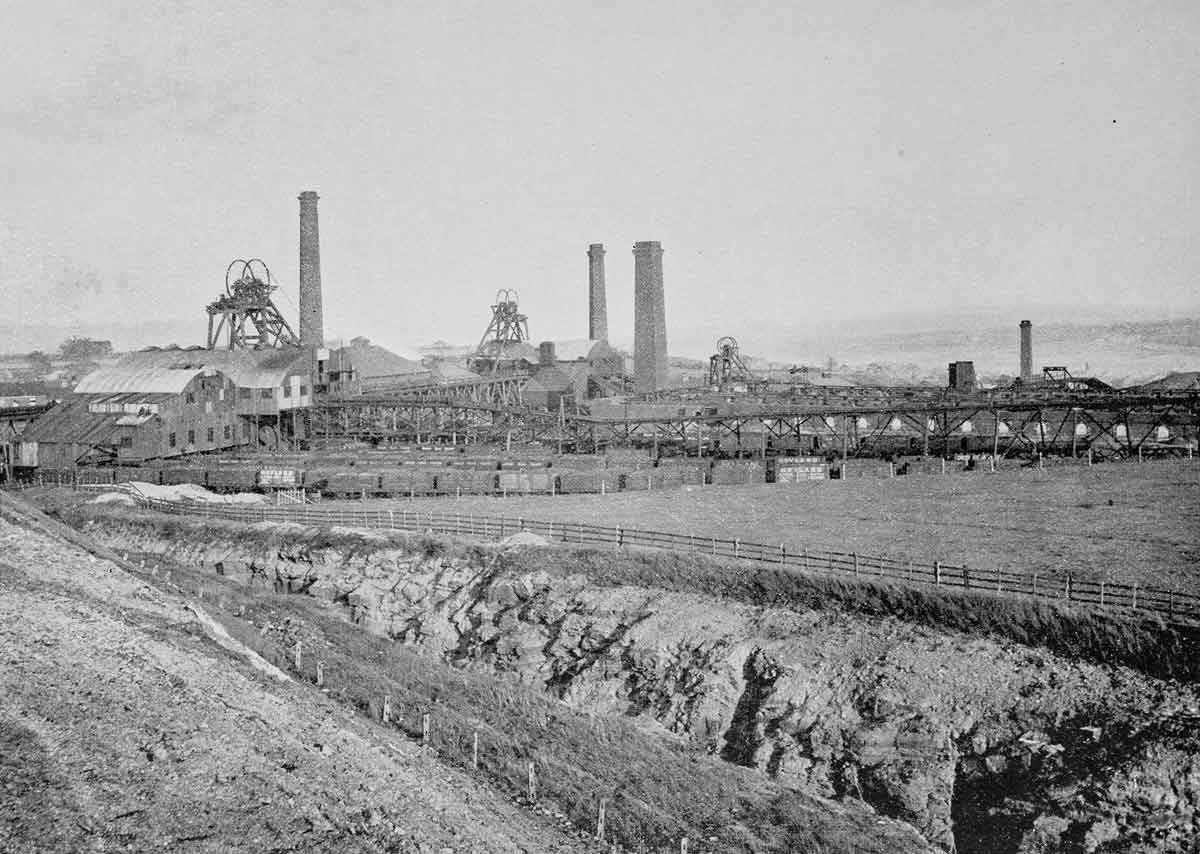

Consider now one of his poems, called “Slough,” published in 1937. To appreciate it, you should know that Slough is the name of an English industrial town that epitomized all the developments Betjeman loathed and feared in England. It begins:

Come friendly bombs and fall on Slough!

It isn’t fit for humans now,

There isn’t grass to graze a cow.

Swarm over, Death!

It continues in this way for four stanzas, but then asks the bombs to spare “the bald young clerks,” for

It’s not their fault that they are mad,

They’ve tasted Hell.

It’s not their fault they do not know

The birdsong from the radio,

It’s not their fault they often go

To Maidenhead

And talk of sport and makes of cars

In various bogus-Tudor bars

And daren’t look up and see the stars

But belch instead.

The poem finishes with another request for the bombs to fall on Slough.

This poem appeared in Betjeman’s 1937 collection Continual Dew (it can be found in his Collected Poems) and no doubt reflected some of the communism, and not a little of the cultural elitism, that were the fashion of the day. But what I want to draw your attention to is another attitude, one for which I can think of only an oxymoronic name: I want you to notice this poem’s “conservative extremism.” Betjeman’s imagery juxtaposes two towns: one lovely, but only present as a lingering image, the other repellent but right there in your face.

The first town is that of Tudor England, pastoral, close to the land, harvesting its food from nearby fields, local and communitarian, without gadgets, but harmoniously interacting with its own flora and fauna. It was to the celebration and protection of the vestiges of such towns and their ways of life that Betjeman devoted a portion of his own work and thought.

However, superimposed on this idyll, and almost effacing it, is an artificial, ugly town, whose brutal economy calls into existence ignorant Hobbesian men and women. Their lives are not worth living, and their artifacts are worthy of nothing but derision and, if possible, destruction. This double vision, this hatred of the city that is and veneration of the one that is not, is what I am trying to capture by the oxymoron conservative extremism.

My question is this: How could someone of such conservative tendencies as John Betjeman gleefully implore bombs to fall on a city in his own beloved country? Not that there is necessarily any difficulty in sympathizing with Betjeman’s attitude toward Slough, or its North American equivalents. I, at least, do not find that sentiment difficult to second. The challenge lies in justifying one’s sympathy on conservative principles.

Graeme Hunter is a contributing editor to Touchstone and Research Professor of Philosophy at Dominican University College in Ottawa. He is the author of Radical Protestantism in Spinoza's Thought (Ashgate).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

27.3—May/June 2014

Religious Freedom & Why It Matters

Working in the Spirit of John Leland by Robert P. George

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor