Boethius’s Complaint

Can the Christian Find Consolation Without Christ?

by Graeme Hunter

One really priceless ornament in the long, and seldom distinguished, history of self-help literature is Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy. It shows what can happen when terrible misfortune collides with human integrity. The fact that its author was a Christian ought to have been a special blessing to fellow believers in the centuries since it was written (about 524). But it has really been more like a worry. The Consolation is unaccountably silent about Christ. Though summoned to seriousness by his own impending execution, Boethius writes as if he were a pagan and appears to derive no solace from his Christian faith.

Secular scholars notice the puzzle without emotion. They usually account for it by saying that Boethius, though a nominal Christian, must have been pagan at heart.

Not surprisingly, Christians have been slow to agree. We want an excuse for appreciating Boethius’s great work. And we don’t want to believe that paganism has powers of consolation denied to Christianity. Yet our attempts to explain what made Boethius silent about his faith have not been impressive. Conjectures about the Consolation’s being an early work, or maybe just an academic exercise, or a deliberate abstention from theology in order to avoid giving theological offense are not really very plausible.

I think there is another explanation. Not only is much of the Consolation structured around medical metaphors for the life of the soul, but an original conception of medicine lies at the heart of its perennial appeal, and explains how a Christian in extremis might have felt compelled to write a work that did not draw in any clear way on his Christian faith.

The Man

Boethius was born in Rome around 480. His patrician Roman family had been Christian since the days of the emperor Constantine 150 years before, but he did not take his faith for granted. He contributed to its development, vigorously contesting some of the disputed theological questions of his day. Among the theological writings usually attributed to him is a skilful summary of Christian belief called On the Catholic Faith.

In his own eyes, however, Boethius was not primarily a theologian, but a scholar of ancient philosophy. Platonism is at the heart of his thinking, but it is the key to more that just his intellectual outlook. It had the ironic double effect of abbreviating his earthly life while assuring his literary immortality.

His commitment to Platonism launched him on the political career that proved to be his downfall. Politics degenerates unless good men do their part, Plato said, so Boethius overcame his reluctance to hold office and served Rome with great distinction for more than two decades. He rose to be Consul of Rome in 510 and then in 522 was appointed to Rome’s highest civil service position, that of chief administrative officer, or Magister Officiorum, of the Western Empire. In that position he was next in power only to the ruler, Theodoric.

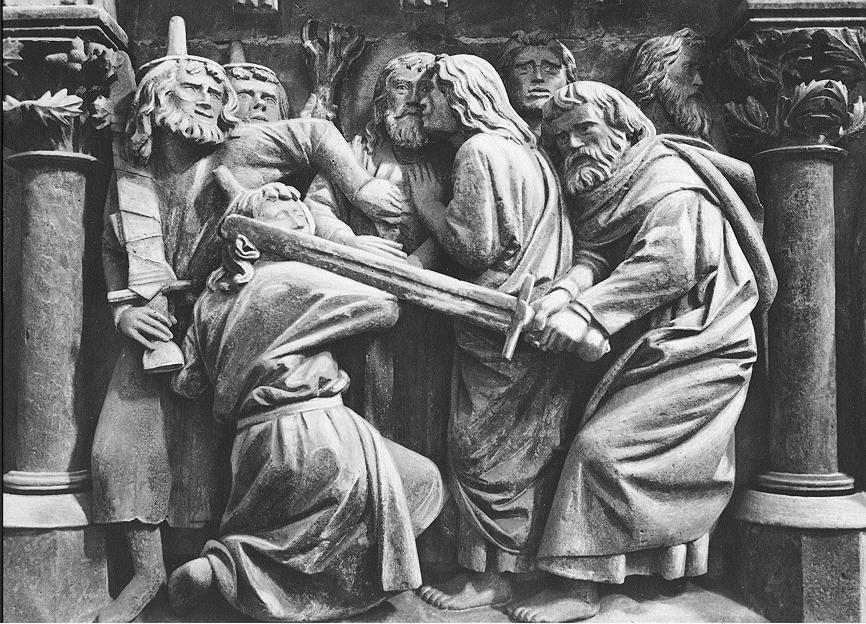

Then, as in some archetypal tragedy, suddenly and irrevocably, he fell. A year after attaining the height of Roman power he was charged with treason, and before another year had passed was brutally put to death.

Graeme Hunter is a contributing editor to Touchstone and Research Professor of Philosophy at Dominican University College in Ottawa. He is the author of Radical Protestantism in Spinoza's Thought (Ashgate).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor