Feature

Vanity Fair’s Thanatos Syndrome

Malcolm Muggeridge, Modern Capitalism & the Culture of Death

by Adam Schwartz

Like many of his forerunners among the famous converts of the last century, Malcolm Muggeridge was an acute social critic whose spiritual pilgrimage was spurred on in crucial ways by his qualms about twentieth-century culture’s direction. Among his principal anxieties was the materialistic ethic he associated with modern capitalism, one he judged corrosive of the core social institution, the family, and one especially manifested in the eugenic impulse. He therefore reproved Western consumerism consistently, and eventually decided that orthodox Christianity was the best—perhaps the only—basis for resistance.1

He sensed early in his life (he was born in 1903) a need to choose to pursue either the quality of life or the sanctity of life, and he chose the latter. He found it to be part of the way of love and the imagination, whereas the former belonged to an ethic animated by power and the will. He increasingly felt that modern Western society privileged the quality of life over its sanctity, and he condemned the culture of consumerist concupiscence that arose from this choice.2

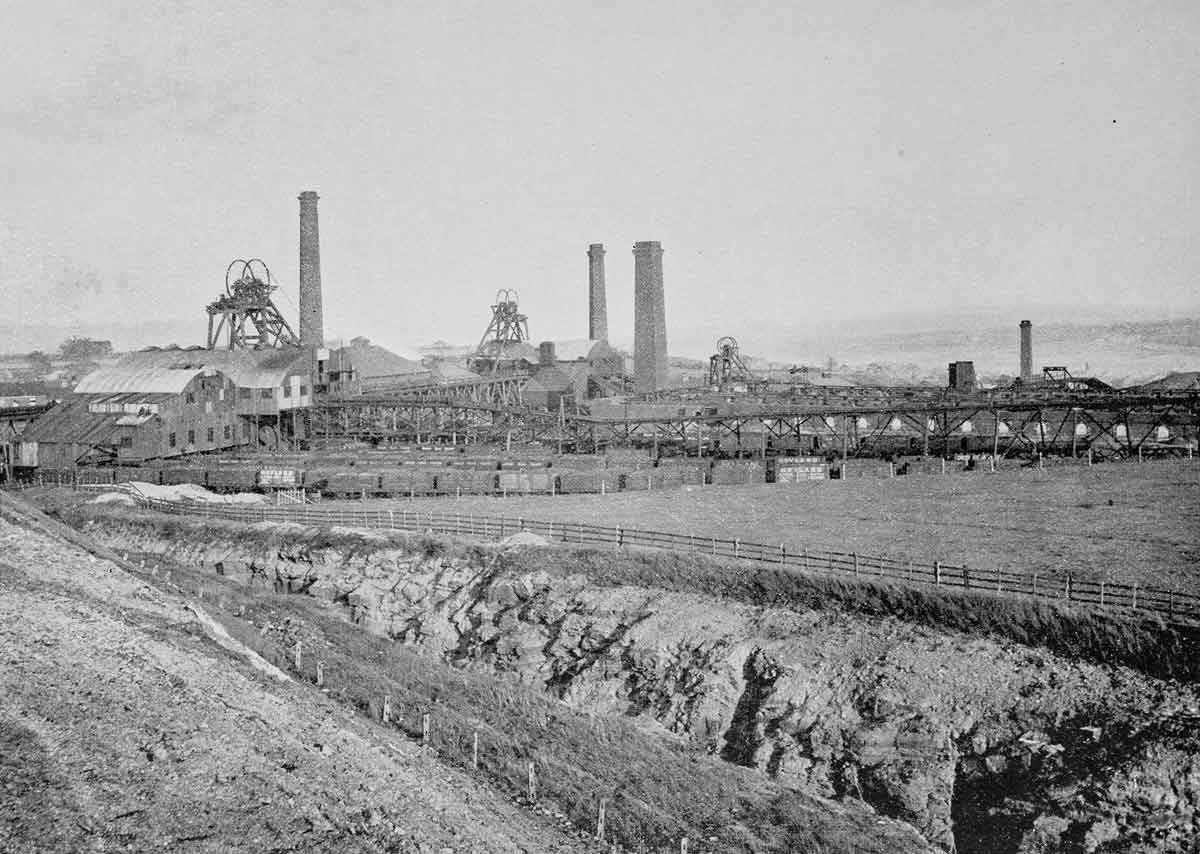

Greed the Mainspring

Muggeridge argued consistently that greed is the mainspring of Western capitalist society and “about the most contemptible of all” such bases, generating an economically lucrative but ethically hollow culture in which the pursuit of happiness was merely the pursuit of pleasure.3 Such a hedonistic civilization was “the most horrible and degraded that ever existed on the earth” and should not be considered civilized.4 He often dubbed the affluent West a gilded “pigsty” and a “zoo.”5

Initially, Muggeridge found consumerist capitalism destructive of individual freedom and integrity. At times he invoked Hilaire Belloc’s idea of “the servile state,” arguing that twentieth-century Western man’s pursuit of pleasure in security would lead him to forsake his freedom voluntarily, creating a “freely constructed concentration camp.”6 Echoing C. S. Lewis and George Orwell, he feared in 1954 that so surrendering personal liberty would entail the “final obliteration of the individual as we know him today” and the advent of a race of mass-minded slaves in thrall to sensuality and the passions: “Leviathan’s belly [is] warm and secure, but dark and confined.”7

Muggeridge regarded the British welfare state as a manifestation, rather than a mitigation, of capitalist materialism’s deadly cultural effects. He contended that the welfare state embodied consumerism’s “shallow and fatuous” ethos, and he thought that concentrating state power to facilitate social security would exacerbate the self-enslavement already fostered by dependence on oligopolies for an everlasting stream of consumer goods and the financial wherewithal to purchase them, leaving Westerners “sleepwalking into our own Gulag, incarcerating ourselves in our own high-rise prisons.”8

Besides threatening man’s liberty and identity, Muggeridge averred, capitalism also spawned an inhuman homogenization and humorlessness, a utilitarian aesthetic inimical to genuine imaginative art, and an unjust distribution of wealth. The latter grew, in part, from the misapplication of Darwin’s model of animal biological development (the “survival of the fittest”) to human society. He concluded that when future eras surveyed the twentieth-century West, they would see a society ruled not by men like gods, but “men like apes . . . and even that will seem rather hard on the apes.”9

Muggeridge was convinced that a culture so seemingly at odds with human nature was unsustainable. Modern Western society was a “nightmare,” one afflicted with a neurosis or madness arising from its consecration of the pleasure principle and its consequent denial of life’s essentially tragic nature.10 He thus felt that wealth was bringing widespread individual and collective despair, especially in places of exemplary affluence like Scandinavia and America, concluding in 1983 that “to believe in man’s capacity to create his own circumstances is a doctrine of despair.”11

Unsurprisingly, then, he considered consumerist capitalism an incarnation of, and contributor to, the “death wish” of the modern West, which was seeking to commit civilizational suicide. As early as 1940, he detected a Western craving for “violence and bloodshed” in entertainment to relieve the “boredom and desolation of mechanized life,” making carnage the “poetry of mass production.”12 By 1958, he was asserting that “the trouble with capitalism is . . . that for the sake of a shilling today it will advance causes which will destroy it tomorrow,” such as trading with Communist states.13

Four years later he speculated that “perhaps the pursuit of happiness will end in extinction,” and by 1970 he was certain that “a neurotic passion to increase consumption” could only precipitate such a culturally self-destructive climax: “We press on through the valley of abundance that leads to the wasteland of satiety, passing through gardens of fantasy; seeking happiness ever more ardently, and finding despair ever more surely.”14

Adam Schwartz is Assistant Professor of History at Christendom College.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

33.1—January/February 2020

Do You Know Your Child’s Doctor?

The Politicization of Pediatrics in America by Alexander F. C. Webster

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor