Feature

Seeing Thro’ the Eye

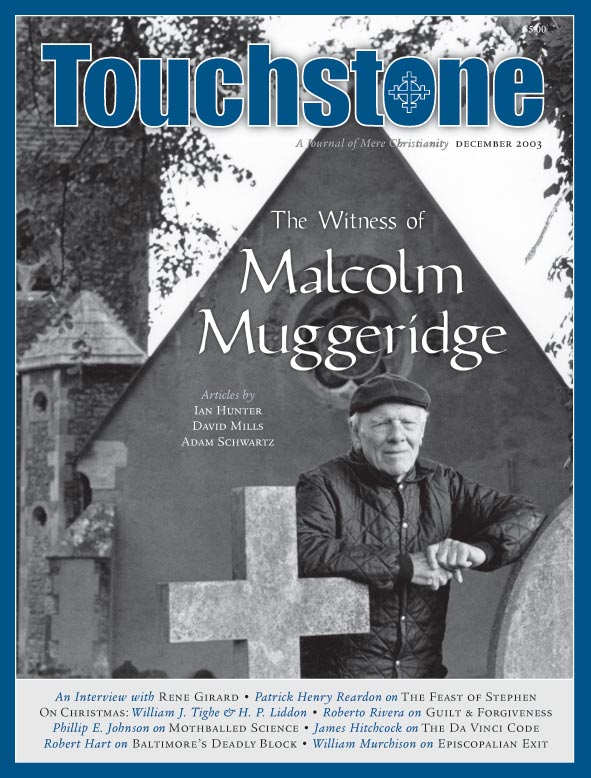

The Prophetic Legacy of Malcolm Muggeridge

by Ian Hunter

No lines were more often quoted by Malcolm Muggeridge than this stanza from William Blake’s Songs of Innocence: “This life’s dim windows of the soul / Distort the Heavens from Pole to Pole / And lead you to believe a lie / When you see with, not thro’ the eye.” Seeing thro’ the eye was a particular gift of his, combined, fortunately, with compelling readability and a willingness to opine on almost any issue at almost any time.

Muggeridge spoke prophetically about many important events of the twentieth century. Prophecy is not so much a matter of predicting the future—though Muggeridge predicted some events with uncanny prescience—as seeing clearly truths others do not or refuse to see. If he was sometimes mocked and seldom heeded—well, that is the fate of prophets, as Jeremiah found out when he got himself chucked down a well. Prophets unsettle our preconceptions and disturb our complacency.

My purpose here is to call attention to what, in baseball parlance, might be called Muggeridge’s “box score,” in the no doubt vain hope that a man so often proved right might be accorded greater attention. I should make clear that Muggeridge himself did not claim to be a prophet. When others applied that label to him, he demurred: “I am no prophet, no, nor prophet’s son,” he said, adapting Amos. “I was a journalist and the Lord took me as I sat at my typewriter.” Yet even as a journalist, he saw through the eye what so many others, of greater fame and status, could not see because they saw only with the eye.

Gandhi’s Writer

In 1925, at the tender age of 22, Muggeridge took his first job, teaching English literature at Union Christian College in Alwaye, southern India. When he was not mocking the college faculty (“Mr. Dryasdust, B.A., B.L., author of notes on this, and notes on that and notes on every possible thing except on life. . . .”) or the students (“The Indian undergraduate is a strange being. He imagines that to be impressive, he must be pompous.”), he was stirring up nationalist sentiment against the colonial administration of the British Raj.

This was particularly evident after Mahatma Gandhi, at that time relatively unknown, paid a visit to the college in March 1925. Muggeridge thereafter corresponded with Gandhi, who published his letters in his newspaper, Young India, thereby earning the distinction of being Muggeridge’s first publisher.

These letters pressed two themes: (a) the impossibility of changing society without first changing men’s hearts; and (b) the artificiality and fragility of a colonial set-up that appeared to most people impregnable. The latter was an early application of his conviction about the futility of trying to live by the will as opposed to the imagination; this theme he derived from his friend Hugh Kingsmill, and it was one to which he returned almost as often as he spoke of seeing through the eye.

To the discerning eye, both themes are evident in a passage, first published in the Calcutta Guardian in 1926, where Malcolm is describing a retarded boy who drove geese, a boy whom he regularly saw on his nightly walk along the Parur Road. It demonstrates how consistent Muggeridge’s writing “style” (a term he detested and never used) remained through his life:

He carries no stick to assist him in keeping order amongst them, but only a large leaf, which he waves slowly to and fro; and one might easily imagine that his speech was nothing but the noise of the wind through this, so like is it to the sound of a forest when, in the evening, a light wind blows. With this he keeps his charges as a compact, disciplined company, not stupidly military in their orderliness, yet not by any means a rabble; rather they remind one of a band of pilgrims, or of workers working voluntarily together. They seem to be not so much numbered and uniformed as to make a harmony of which he is the conductor: not so much to march in step as to dance with perfect understanding of each other’s movements.

One day he saw another boy driving the geese, “a bouncing, bumptious fellow, who carried a switch like a sergeant-major, and who shouted at the geese as sahibs shout when they want something.” Predictably, the geese ran around squawking, some getting lost and others run over. He will not draw a moral from the contrast (“a thankless task”), but writes instead that he envies the first boy.

Ian Hunter is Professor Emeritus in the Faculty of Law at the University of Western Ontario. He is the author of biographies of Robert Burns, Hesketh Pearson, and Malcolm Muggeridge.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on literature from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

Support Touchstone

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor