Feature

Church, State & Conscience

The Freedom of the Church & the Responsibility of the State

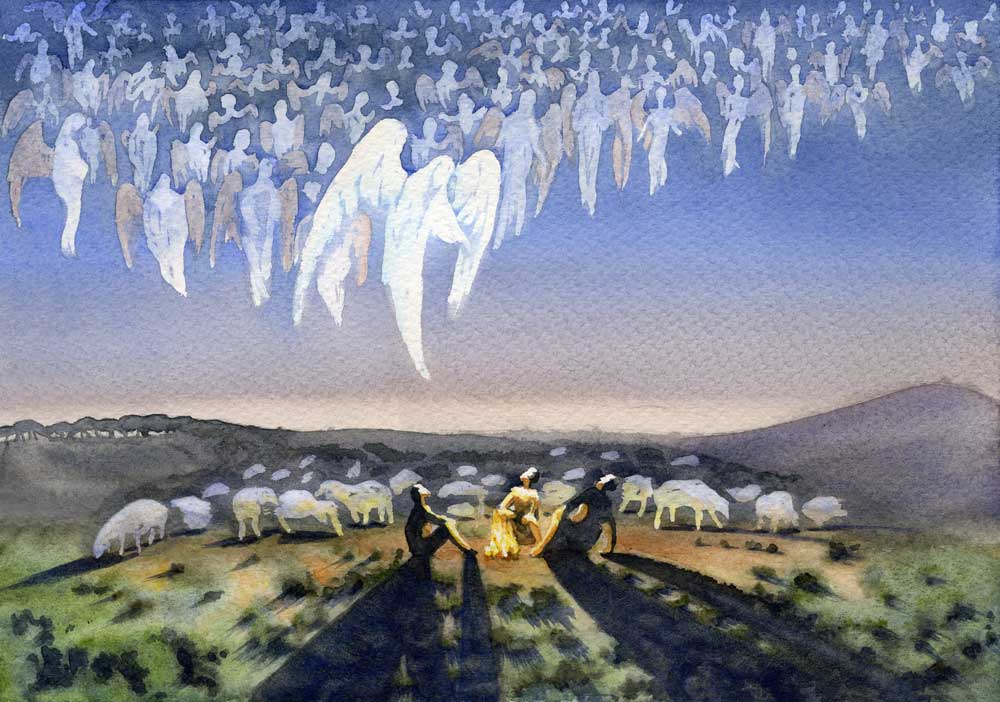

On January 24, 2002, more than 200 religious leaders representing creeds and peoples from around the world gathered in Assisi, Italy, the home of St. Francis, at the invitation of Pope John Paul II, to participate in the second Day of Peace for the World. (The first was held on October 27, 1986.) Catholic, Protestant, and Eastern Orthodox Christians, Jews, Muslims, Confucians, and Buddhists all came together to pray for that peace that had been so brutally repudiated in the terrorist attacks of September 11.

While crediting the pope’s good intentions, some Catholics—and other Christians—have, nonetheless, disapproved of the Assisi gathering. These critical voices allege that John Paul II’s inclusion of non-Christians compromised the claims of Christianity to be divinely revealed truth. These critics believe that by appearing with non-Christian religious leaders, and despite the pope’s statement that there were no moments of common prayer during the Day of Peace, John Paul II continued and deepened a fundamental mistake made at the Second Vatican Council.

Are these critics correct about Vatican II? Assuming John Paul II is, as he has always claimed, a faithful interpreter, even implementer, of Vatican II, did that council teach propositions that are incompatible with and even undermine Christian truth claims? More specifically, did Vatican II’s teaching on the subject of religious freedom fundamentally break with Catholic tradition? Did Vatican II put the Catholic Church on a path that fosters, and necessarily leads to acceptance of, religious indifferentism?

Conscience & Coercion

In Dignitatis Humanae (DH), the fathers of the council set forth principles of religious freedom for what we may call “the modern era.” Taking note of the “spiritual aspirations” of contemporary man, particularly his yearning for freedom, the council’s “Declaration on Religious Freedom” called for protection of the right of each person to religious liberty within the constitutional order. The declaration found this “civil right” to be rooted in the personal dignity and social nature of the human being. Thus, subject (only) to the just demands of public order, all forms of “coercion” aimed at forcing a person to act contrary to his conscience in matters of religion were declared to be unjust.

It is commonly acknowledged that the thinking of John Courtney Murray, S.J., shaped the development of this teaching, and we will spend some time on that point below. However, it is also true that the council saw itself as “develop[ing] the teaching of recent popes on the inviolable rights of the human person and on the constitutional order of society.” (DH 1) It is, however, on precisely this point—conformity to the teaching of prior popes—that Dignitatis Humanae is frequently challenged. Although a thorough analysis requires systematic treatment by historians and theologians, we would like to note a few points.

First, critics often allude to the teaching of one prior pope in particular to illustrate what they claim are discontinuities between the larger tradition and the teaching of Dignitatis Humanae—Pius X. Leaving aside the point that, from the perspective of Catholic faith, the teaching authority of an ecumenical council such as Vatican II is superior to the non-ex cathedra teaching of an individual pope—something that would resolve the matter if there were a contradiction—we might consider whether there is a contradiction between the teaching of Pius X and that of Dignitatis Humanae.

Perhaps the heart of Pius X’s teaching is contained in his encyclical letter, “On the Doctrine of the Modernists,” and the companion “Syllabus Condemning the Errors of the Modernists,” both issued in 1907. In these documents, he grapples with the problems posed by Catholics adhering tenaciously to heretical doctrines as if by right. As a result, he condemns the view that “[i]n proscribing errors, the Church cannot demand any internal assent from the faithful by which the judgments she issues are to be embraced.”1 In other words, according to Pius X, the Church may demand the internal assent of its members. Vatican II asserts that man “must not be forced to act contrary to his conscience” (DH 3).2 Is this a contradiction?

Wheat & Tares

While Pius X speaks to the church’s right, Dignitatis Humanae speaks of the individual’s right. These rights do not contradict each other. The Church presents the truth undiminished and may demand that its members adhere to its tenets. But individuals are to be free in the civil order to heed the Church—to join the Church and even to leave the Church—or not, even if they are mistaken in that choice. Dignitatis Humanae expressly “leave[s] intact the traditional Catholic teaching on the moral duty of individuals and societies towards the true religion and the one Church of Christ” (DH 1)3—precisely the moral duty that Pius X was at pains to assert4—but supplements that teaching with new (but not contradictory) teaching on how the individual is to find that truth.5

Robert P. George is McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence and Director of the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions at Princeton University (web.princeton.edu/sites/jmadison). His books include In Defense of Natural Law (Oxford University Press) and Conscience and Its Enemies (ISI Books). He has served as chairman of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

William L. Saunders is Senior Vice President and Senior Counsel at Americans United for Life.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor