Life & Death After Christendom

The Moralization of Religion & the Culture of Death

by H. Tristram Engelhardt, Jr.

The third millennium opens as a post-Christian, postmodern, post-metaphysical, post-traditional age. The ubiquity of the prefix post underscores the radical changes that mark our times. We have experienced a rupture, a fundamental change in our dominant self-understanding.

We are first and foremost after Christendom. We no longer live in a culture that directs history from Creation, the Fall, and Redemption to the Second Coming and the Final Judgment. Most no longer live as if they expected to be judged at death or the world at the Second Coming. In the light of its liberation from ecclesiastical control, the marginalization of the culture of worship and the loss of a history rooted in human redemption have largely gone unnoticed. The Christian message in the public forum now often seeks expression in the lingua franca of the principles of moral theory. Most significantly, liturgical life has been relocated within a private space, and the moral discourse of the public forum has been rendered thoroughly secular. Crucially, there is little suspicion that praying well is essential to morally knowing rightly. Morality is now to stand on its own without being located within a prayerful turn toward God.

The culture of death can only be understood in terms of the larger issue of the post-Christian culture within which we find ourselves and the radical cultural transformation that frames our age with its cardinal affirmation of autonomy and liberation. These phenomena are allied with the marginalization of the culture of worship and moralization of religion, the view that the truth of religion lies in the morality it sustains, which leads to a culture of death affirming abortion, as well as physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia.

As a consequence of this metaphysical and historical loss of orientation, our society does not possess a univocal sense of human destiny or purpose. In the wake of this loss, we have the possibility of alternative histories and competing moral narratives, along with the emerging specter of nihilism. The very character of those developments and the appropriate responses, if any, are themselves controversial.

For traditional Christians, these developments can be nothing but foreboding. After all, the traditional Christian focus is on liberation through submission to God. For some others, these changes mark the vanguard of human development and self-liberation from arbitrary authority and superstition. The new culture does not regard itself as a culture of death, but as a culture of life and liberation. Each culture is to the other a counter-culture, marking a profound break in our history, our self-understanding, and our appreciation of life and death.

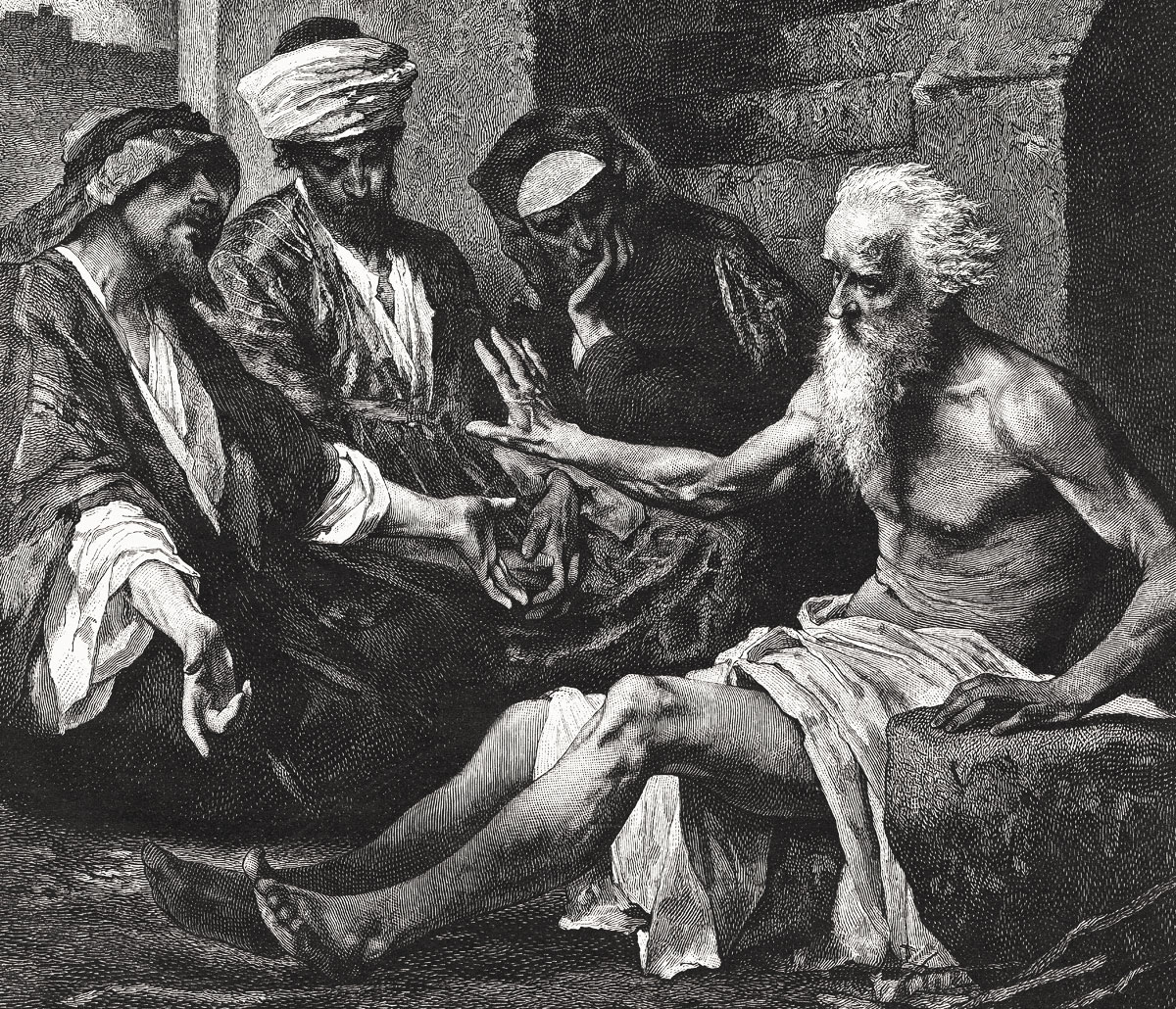

Liturgical Loss & Moralization

To understand the emergence of our new culture of death, two intertwined matters must be addressed. The first involves the move from a liturgical to a post-liturgical culture. By this I mean in part the secularization of a once-Christian culture, a culture that in the past celebrated its prayers in public spaces and thickly sanctified its life by an intensive rhythm of prayer, fasting, and almsgiving. My analysis is not necessarily a call for the reestablishment of Christendom. Rather, and most crucially, it is a recognition that there is an epistemic bond between moral knowledge and the spiritual life. Believing and worshipping rightly bring moral knowledge and discernment.

In this brief study, this crucial claim will be explored, though not defended. This view finds adequate elaboration and defense in the works of St. Isaac the Syrian (613–?),1 St. Symeon the New Theologian (949–1022),2 and St. Gregory Palamas (1296–1359),3 as well as elsewhere.4 Moral knowledge grows through a rightly ordered spiritual and liturgical life. Unlike the different, albeit important, claim of Catherine Pickstock regarding the liturgical consummation of philosophy, the claim here is one concerning the spiritual nurturing of the human heart as a moral and noetic faculty.5

A second and related matter concerns the moralization of religion, by which I mean the late-Enlightenment understanding that the core truth of religion is to be found in a just and moral life. In the grip of Enlightenment dispositions regarding religion, few are inclined to recognize that the moral life once disengaged from a culture of worship loses its grasp on the moral premises that rightly direct our lives and foreclose the culture of death. The culture of death develops naturally from the moralization of religion, in that morality as secular cannot appreciate the moral premises needed to understand the evil of the culture of death. By default, secular morality is driven to acknowledging as central the permission of actual moral agents, thus rendering the availability of abortion, consensual homosexual acts, and physician-assisted suicide, along with euthanasia, licit. Then, through the affirmation of free choice, permission becomes not merely a side constraint as a source of authority, but as autonomous choice to be valued in itself.6 The solution to the moral decrepitude of our culture lies in philosophy as an ascetical, noetical undertaking, not as a discursive, intellectual endeavor.7

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

33.2—March/April 2020

Christian Pro-Family Governments?

Old & New Lessons from Europe by Allan C. Carlson

37.5—Sept/Oct 2024

Why Law Schools Can't Teach Law

A sidebar to How Law Lost Its Way by Adam MacLeod

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor