The Humble Artist

The Christian Imagination: G. K. Chesterton on the Arts

by Thomas Peters

San Francisco: Ignatius, 2000

(157 pages; $12.95, paper)

by Eric Scheske

In one of his most popular books, What’s Wrong with the World, G. K. Chesterton wrote: “The average man cannot cut clay into the shape of a man; but he can cut earth into the shape of a garden; and though he arranges it with red geraniums and blue potatoes in alternate straight lines, he is still an artist; because he has chosen.”

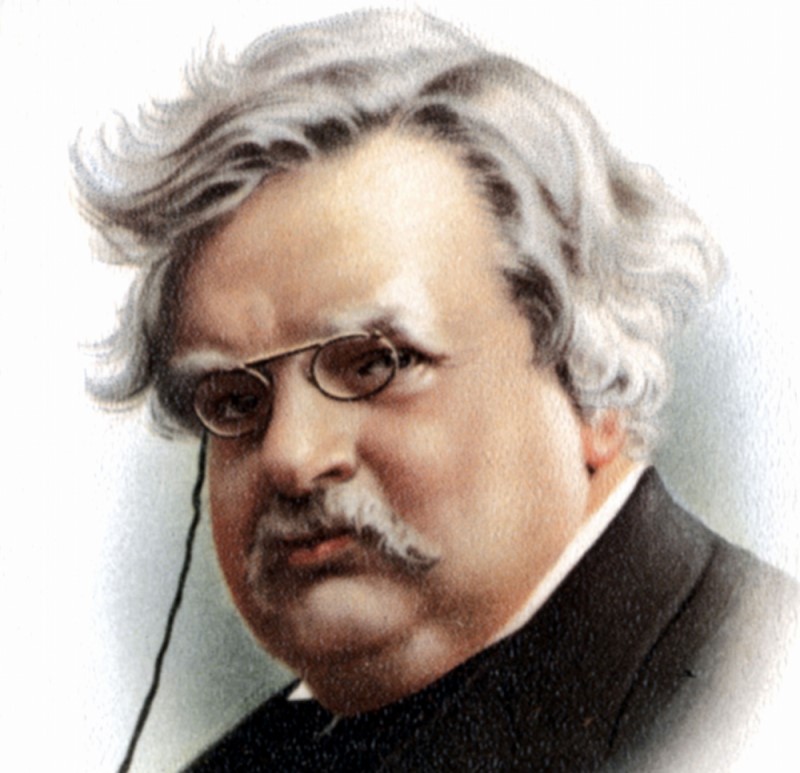

Chesterton was a giant of an artist, but more importantly, he was a giant of a man who understood what it meant to be a man: a creature made in God’s image, but still only a creature; a wonderful being made to wonder; greatness made to be humble. Those apparently inconsistent traits, Chesterton knew, are combined in every man.

These paradoxes are explained in Thomas Peters’s enjoyable new book, which shows both how they combined harmoniously in Chesterton himself and how they combined in Chesterton’s views on art. Because everyone is meant, at some level, to be an artist, the book speaks to all of us, regardless of our artistic level.

Peters starts with a clear picture of Chesterton. Chesterton, Peters tells us on the first page, was “a brilliant and entertaining Christian apologist and a fierce defender of the faith,” but also “a frolicsome child of the great Creator.” He was trained as an artist, opting as a young man to attend the Slade School of Art instead of a university, but quickly became a journalist—then a poet, a novelist, a public philosopher, and a Christian apologist.

Chesterton combined, in strong degrees, the paradoxical traits described above. Although he was extremely prolific—a writer whose nearly 100 books and thousands of essays touched almost every topic under the sun, from religion to politics to economics—he was down-to-earth. He would prefer to sit in a pub swilling beer to discussing religion and philosophy (though he relished the latter, too).

Fittingly, Chesterton’s artistic endeavors ranged from the lighthearted to the serious. His lighter artistic endeavors included “rowdy songs, drinking songs, and fighting songs,” little poems, and stories. Peters gives examples of all of them, but shows that Chesterton’s lighter endeavors often carried a heavy point.

Even something as seemingly inconsequential as men singing in a tavern was an important topic to Chesterton, especially if someone was trying to eliminate it. “Once men sang together round a table in chorus; now one man sings alone, for the absurd reason that he can sing better. If scientific civilization goes on . . . only one man will laugh, because he can laugh better than the rest.”

This combination of lightness and heaviness pops up throughout the book. Chesterton, for instance, was an accomplished sketcher, and Peters shows us five samples of his works—all cartoons. One drawing accompanies a poem about sailors who try to give an ungrateful fish humanly comforts. The fish, being only a fish, is ungrateful, so the sailors put him on trial, and Chesterton’s drawing shows an indignant fish being interrogated by an even more indignant sailor. This silliness, however, carried a serious message. It, Peters explains, “poked fun at the overzealous humanitarians who do more harm than good by seeking to help people who neither need nor want their help.”

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on imagination from the online archives

11.5—September/October 1998

Speaking the Truths Only the Imagination May Grasp

An Essay on Myth & 'Real Life' by Stratford Caldecott

more from the online archives

15.6—July/August 2002

Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World

The Shape of Divine Providence & Human History by James Hitchcock

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor