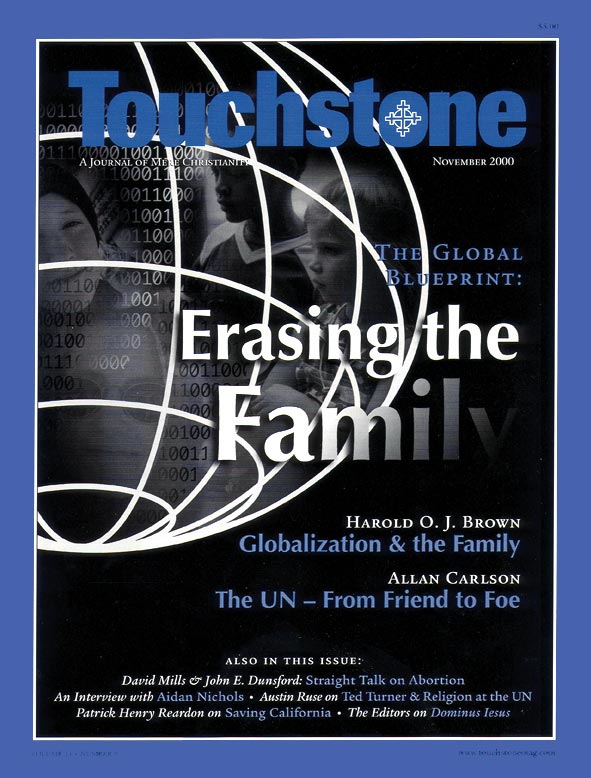

The UN—From Friend to Foe

The Fate of the Family in the Triumph of Socialism over Christian Democracy

by Allan Carlson

Early this summer, several hundred advocates for life and family autonomy squared off in a war of words and paper against a much larger and better-funded band of feminists and sexual radicals. The United Nation’s “Beijing Plus Five” Conference on the Status of Women, held in New York, was the battleground this time for rival Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), following the earlier clashes at UN meetings in Cairo (1994), Beijing (1995), Copenhagen (1996), Istanbul (1997), and Nairobi (1998).

The stakes have been high, for these meetings are now shaping international policy and law regarding the status of the family, including husband-wife bonds, parent-child relations, and human reproduction. For the large majority of nations that have signed UN treaties regarding the “rights” of women and children, the consequences are great, for these treaties contain enforcement mechanisms that are proving to be surprisingly effective (e.g., the Australian state of Tasmania was forced to give favorable legal treatment to homosexuality while Canada is under pressure to suppress spanking). But even for that handful of states that have not ratified these treaties (notably the United States and a few Islamic countries), the implications are large. “International precedents” shaped by the UN process have begun to enter American judicial decision making, while the Clinton administration has used Executive Orders to implement sections of both the “children’s” and “women’s rights” conventions.

Curiously, in its early years, the United Nations actually operated on remarkably strong pro-family principles. Its shift toward extreme “equity feminism” and sexual radicalism came only later. How did this happen?

Two factors shaped the attitudes toward the family to be found in the early years of the United Nations. To begin with, the horrors created by the Nazi occupation of Europe—the death camps, the eugenics campaigns, the experimentation on human subjects—were vivid images in the minds of those who gathered in San Francisco in 1945 to inaugurate the new organization. It became important both to restore respect for the “human person” and to rescue “the family” as an ideal from the race-motivated distortions of Adolf Hitler.

Second, four rival worldviews emerged out of the rubble of World War II, seeking to shape the postwar environment and the new organization. Dominant at the political and military level was the rivalry between the communism found in the Soviet Union and the liberal democracy of the Americans: the period from 1945 to 1990 is commonly seen through the lens of the resulting Cold War. But at the social policy level, and specifically at the family policy level, a different competition of worldviews ensued: here, between Christian democracy and social democracy.

The “Christian Democratic” Episode

The Christian Democracy movement that took form in Europe in the mid-1940s claimed to be something altogether new. Christian political movements before 1930 had commonly shown suspicion of modernity, distrust of democracy, opposition to individualism, and hostility to the legacy of the French Revolution.

Yet by the 1930s something fresh and creative was emerging among Christian thinkers, with particular clarity in France. The key figure was Emmanuel Mounier. Writing in the Catholic idea-journal, Espirit, Mounier worked out a “Christianized” version of individualism, called “personalism.” This approach saw every human person as unique, a “free agent” with “inherent” moral qualities, and with rights rooted in a natural law. This vision placed strong emphasis on the importance of developing all dimensions of the human personality: “social as well as individual and spiritual as well as material.” Mounier emphasized that the full flowering of the individual would come only through social structures such as family, local community, and labor union. He called for creation of a revolutionary Christian party, one “hard,” one worthy of Christ, and one “radical” in its social-economic vision.1

In 1943, a young Catholic philosophy student and disciple of Mounier, Gilbert Dru, drew up a manifesto for postwar Christian Democratic work. He emphasized the revolutionary quality of true Christian action: the whole person must become engaged, not just as a cog in a party machine, but as a militant working to build a new France on radical Christian principles. A year later, Dru paid for this manifesto with his life, being shot by the German gestapo in Lyons.2

Allan C. Carlson is the John Howard Distinguished Senior Fellow at the International Organization for the Family. His most recent book is Family Cycles: Strength, Decline & Renewal in American Domestic Life, 1630-2000 (Transaction, 2016). He and his wife have four grown children and nine grandchildren. A "cradle Lutheran," he worships in a congregation of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. He is a senior editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on family from the online archives

more from the online archives

35.4—Jul/Aug 2022

The Death Rattle of a Tradition

Contemporary Catholic Thinking on the Question of War by Andrew Latham

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor