Breaking the Ties That Bind

Globalization & the Family

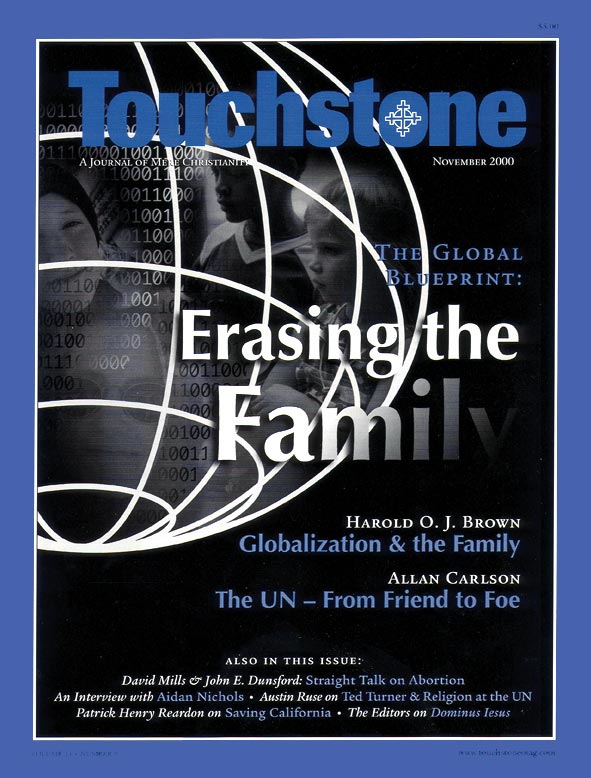

by Harold O. J. Brown

Those who have been entertained by the American and international media with accounts of the 1998 White House melodrama will remember one of the deeper philosophical questions that emerged. The American president said, in effect, that everything depends on what is meant by “is.” In one pseudo-scholarly paper written to parody the situation, supposedly presented at a world meeting of “-isicists,” one contributor argued that “is” does not exist, or exists only for an infinitesimally tiny instant, for we pass instantaneously from “was” to “will be” with only the briefest of seconds at “is.”

Defining Our Terms

When I confront the topic that has been assigned to me, I sense a similar perplexity. Globalization is a scientific- or mathematical-sounding term, and perhaps it can be defined precisely. We might define it as meaning the situation in which national and regional loyalties become subordinated to the affairs of the entire globe. It is commonly used to refer to economic change, the integration of production and other economic activities across national boundaries, but it can also mean social, cultural, linguistic, and even religious integration.

But let us leave globalization aside for the moment: What is meant by “family”? Former US President Jimmy Carter, who was in office from 1977 to 1981, summoned a White House Conference on Families. This conference, among its other accomplishments, sought to define precisely what was meant by the word family. As with certain other words, until then, everyone thought that he knew what it meant. The purpose of the White House conference was to build up and strengthen families and to reaffirm “family values.” Suddenly it appeared that we were not quite sure what it was that we were supposed to build up and strengthen. To avoid accusations of favoring the “traditional family”—two parents, children, perhaps with grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, all related by marriage or by blood—a new definition was proposed. The conference came up with a rather generic definition of family as “a group of people living together.”

This could enable us to consider a college fraternity, an army platoon, or even four convicts sharing the same prison cell a family. Perhaps here in Geneva we could call ourselves, for four days at least, one big family. I think that we are more precise, and whether we think primarily of the so-called nuclear family of husband, wife, and children, or of the extended family, including grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins, and in-laws, we think of a group of people bound together, more or less for life, by covenants, both formal and natural. And thus, when I seek to examine the phenomenon of globalization in its influence upon the family, this is what I, too, mean by family.

When we come to globalization, I am reminded of a statement made years ago in a book by Peter Berger and Richard John Neuhaus. In the late 1960s the word and idea of revolution was “in.” Berger and Neuhaus believed that most people who used the word had no idea what it really meant. They said, in effect, “When they [i.e., student radicals] think of revolution, they think of something fine and noble. When I think of it, I think of dead children in the streets.” When its advocates think of globalization, they think of universal equality and universal harmony, of something like a universal Disney World, in which everyone has a beautiful costume, smiles are everywhere, and there are no paper plates and styrofoam cups left lying on the ground at night.

When I think of globalization, I think of something more like Jean Raspail’s Camp of the Saints, in which the building pressure of the impoverished millions of East Asia and the cowardly indecisiveness of the rich nations of Europe lead not to universal prosperity but to worldwide misery. Instead of the benefits of science, industry, education, and wealth being expanded to spread around the globe, the starvation, sickness, and ignorance of the poorest nations overflow the world.

The Fate of the Family

Globalization is not meant to work that way (and neither was revolution intended to lead to dead children in the streets). It was to mean the extension, to the entire world, of liberty, which Jean-Jacques Rousseau presented as one of the two essential goals of every government (the other being equality). But notice how he defines liberty and its implications: “Liberty, because every particular dependency is that much power taken by force from the body of the State, and equality, because liberty cannot exist without it.”1

Every particular dependency? Is not particular dependency precisely what is meant by family? Every particular dependency robs and weakens the State? Then liberty in his sense is incompatible with the survival of the family in the traditional sense. Rousseau’s concept of liberty involves breaking every interpersonal and intergenerational tie, making everyone dependent on no one—on no one, that is, except the State.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on family from the online archives

33.2—March/April 2020

Christian Pro-Family Governments?

Old & New Lessons from Europe by Allan C. Carlson

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor