The Domestic Workplace

Feminism, Careers & the Family: Who Has Gained? Who Has Lost?

by Allan Carlson

The modern history of “women’s liberation” can be read as a tale of increasing human bondage and female submission to the corporate state.

By “corporate state,” I mean the union of the giants—big business and big government—who, whatever their surface disagreements, share a deep and lasting interest in the weakening of family bonds and the disappearance of the autonomous home.

Before expanding on my argument, I want to add two caveats: First, I am not very concerned, here, with the attitudes and fate of the wealthiest 5 to 10 percent of the population, now or in the past. The rich and powerful—women as well as men—have always enjoyed special choices or dispensations that have set them apart. I want to focus instead on the attitudes and lives of the 90 to 95 percent: those fated by birth or circumstance to labor in order to survive. In other words, I am less concerned about people in careers such as physician or lawyer or stockbroker and more concerned about folk in “careers” such as cafeteria worker, janitor, or assembly line.

Also, I am not here to defend the so-called “traditional family” or “Ozzie and Harriet family” of the 1950s. There were architects of this family model, one that I have described elsewhere1 as “a household engineer bonded to an organization man in a companionate marriage focused on informed consumption in the suburbs.” While I am fascinated by the rise and fall of this historical episode, I would emphasize the inherent weaknesses of this family system, which left it as a “one-generation wonder” incapable of transmitting its set of values to subsequent generations.

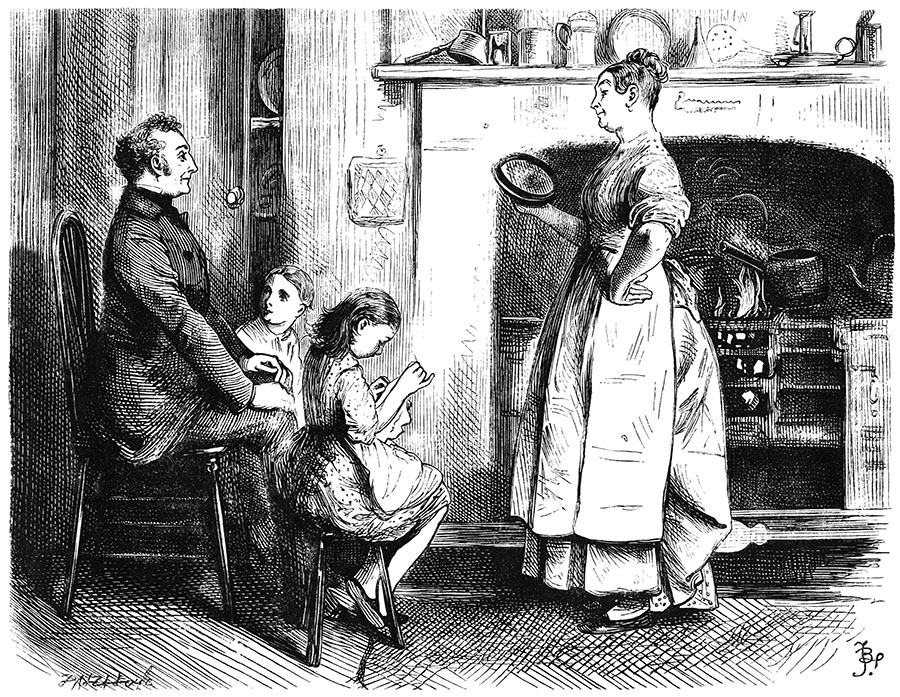

Work & Home Before Industrialization

Indeed, to understand our current situation we must search much deeper in the past. And there we find a basic revolution in human social affairs, one that started about two hundred years ago, as the process of industrialization began its work. This kind of organization rested on the use of power machinery, expanded markets, a highly refined division of labor, and strict worker discipline. Most important for our purposes, it also involved an altogether new and radical separation of “work” from “home.” Until about 1800, for all of human history, the vast majority of people had lived and worked in the same place; that is, their dwelling place was also their work place. The peasant or family farm or the craftsman’s shop or the fisher’s cottage was the normal pattern of human life for many thousands of years.

If we can shed our modern biases for a moment, we might even appreciate some aspects of the lives lived in these ways. Marriage brought a union of the sexual and the economic, in a manner that brought gain to both partners. Their homes were rich in daily event, places where husband, wife, and children all shared in the work of the family enterprise. Children were economic assets in these productive homes, each one welcomed warmly into the family circle. The household was the center of education in basic and advanced skills. Estimates suggest that, in this household-centered milieu, at least 60 percent of all goods were created and produced by the women. In such context, women found deep and real satisfaction: as the guardians of function-rich, economically productive homes, their fertility and their creativity combined in ego-fulfilling ways.

Even in our own century, we can see surviving pockets of this old order, focused on domestic production. In her brilliant study entitled The Transformation of Rural Life, Southern Illinois, 1890–1990, anthropologist Jane Adams describes life for the vast body of agrarian American women, circa 1900:

Work aimed at earning a cash income and work that provided daily needs were not sharply distinguished, just as child care was not a discrete body of activities. Similarly, work that was appropriate to men and to women was, in many cases, not strongly distinguished.

Allan C. Carlson is the John Howard Distinguished Senior Fellow at the International Organization for the Family. His most recent book is Family Cycles: Strength, Decline & Renewal in American Domestic Life, 1630-2000 (Transaction, 2016). He and his wife have four grown children and nine grandchildren. A "cradle Lutheran," he worships in a congregation of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. He is a senior editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on family from the online archives

31.5—September/October 2018

Errands into the Moral Wilderness

Forms of Christian Family Witness & Renewal by Allan C. Carlson

more from the online archives

35.4—Jul/Aug 2022

The Death Rattle of a Tradition

Contemporary Catholic Thinking on the Question of War by Andrew Latham

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor