The Fairy-Tale God

Truth & Deceit in Children’s Fiction

by S. M. Hutchens

My girls are no longer young, but when they were, I paid some attention to the children’s books they brought home from the library. Martha and Laura had orthodox tastes, and no interest in anything weirder than Dr. Seuss. Every now and then, however, they would bring home something that struck me as more than odd, but bad, and on rarer occasions more than bad, but genuinely evil. I began to keep my eyes open.

When I began to work as a librarian, cover art and titles of children’s books that looked a bit “off” attracted my attention. So did the popular literature of professional librarianship, which indicated that there was deep moral sickness in the library world. Marian the Librarian, it turned out, was a very accurate stereotype of a person all too common in the libraries: the modestly educated libertine with a firm belief in her intellectual superiority and zeal to enlighten the local clodhoppers to the point where they can recognize it.

Marian has come into her own in our day, and she is going after the bourgeois prigs in River City with a vengeance. Exposing the village children to Rabelais and Balzac is no longer enough. She is now on to everything that Michael and Diane Medved have said, in Saving Childhood, corrupts the happiness of innocence. The American Library Association, Marian’s political arm, in league with the ACLU and the like, is fighting and winning major court battles against a community’s right to filter its public library’s Internet connection, and thus is making everything imaginable, and some things that aren’t, available to every patron who can operate a computer. Vigilant parents can protect young children from Internet pornography to approximately the same degree they could from dirty pictures that got handed around the playground in the old days, which is to say, some, but not completely. Such things have always been in the world, and innocence is still its own best protection. People don’t get corrupted unless they wish to be.

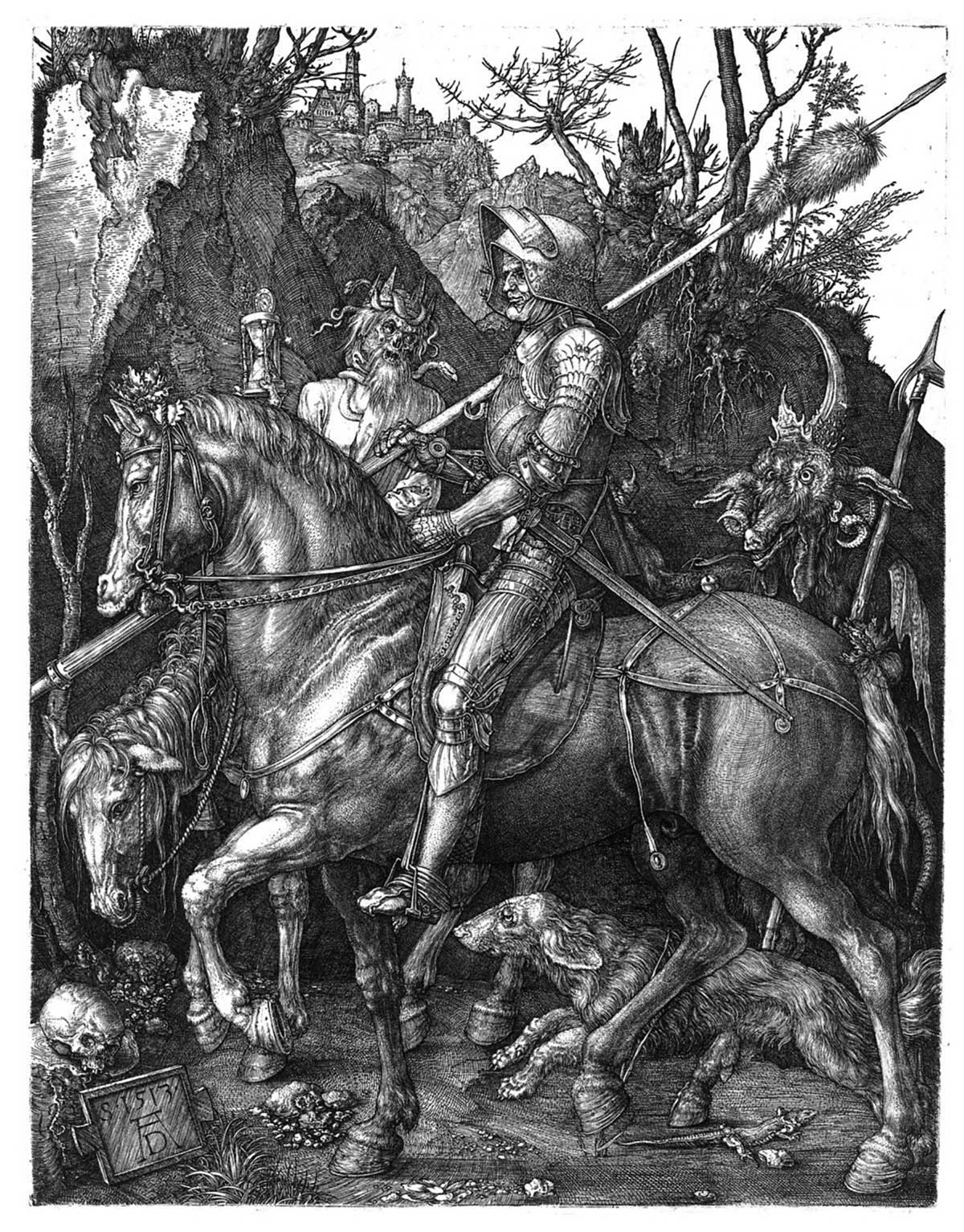

I am concerned here with something more subtle, something that encourages despair more than lust, and is more difficult to detect and fend off. I refer to the numerous attempts by modern tellers of tales to impress into children’s minds stories that are what Lewis’s hrossa called “bent”—twisted accounts of what is and what should be—and to convince those who read them to children that these stories are just the things they ought to hear. Stories are images of reality that invite participation of the hearer’s imagination. They have an attractive power that invites us to take part in them, to find our places in the story’s world. Bent stories are bad places to wander into, for, made as they are from stolen bits of heaven, they hold out the promise of something good, but subject the imagination, once it is captured, to the philosophy of hell.

Tales for Our Time

Several months ago while browsing in the bookstore Half Price Books, I found an interesting collection of stories that I decided on the spot was indeed worth half price, and bought it, mostly on the basis of its fascinating title and cover illustration. On the cover of The Outspoken Princess and the Gentle Knight is a little girl with firmly planted feet, right arm akimbo, and in her left hand a golden sword. Bowing humbly at her feet is a king whose own sword has been placed on the ground. (This is one tough kid, who obviously never learned that only boys carry swords.) The editor, Jack Zipes, was at the time of publication a professor of German at the University of Minnesota, whose books include Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion and Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England.

In the introduction, Professor Zipes tells us that there are problems with the magic of the traditional fairy-tale collections. We don’t “pause to think that many of the tales that have become part of the classical canon like ‘Snow White,’ ‘Sleeping Beauty,’ and ‘Cinderella’ may have dubious messages when it comes to the depiction of gender roles, violence, and democracy.” “Since,” he says, “we tend to internalize the values we were exposed to as children without seriously questioning them, there is a danger that we may perpetuate the cultural and political messages of traditional fairy tales rather than seek out tales more appropriate to the social temper of our times.”

Up until relatively recently similar tales continued to “provide glimpses of happy heterosexual marriages, stable class systems, and successful heroes with wealth and power that may have been satisfactory for patriarchal world orders, but they offer very little hope for change in view of present day conditions and upheavals.” In other words, what is both right and possible for the imagination changes with the times. Its life should mutate to reflect as much hope for happiness as the times permit, and in accordance with the wisdom of the new age. Fairy tales, says Professor Zipes, reflect utopia, a place we envision in our dreams. It constantly shifts its shape and meaning, depending on the real conditions of our society.

With an introduction so philosophically shallow and morally perverse (as though there were no perduring desires of the human heart, as though some utopias aren’t dreams of terror, as though we must bow to “progress”), you can imagine what I expected to find in this book. What was actually there, however, surprised me, and brought me to wonder whether it is in fact very easy to “bend” a tale in accordance with the editor’s belief that societal changes could and should affect what the imagination craves. If fathers are in short supply in the ghetto, and whole marriages are rare in the suburbs, does this mean that children, directed by radical scholars, can or should quit entertaining the imagination of strong kings who reign with their queens, who love them and destroy what threatens them? To be sure, there were what appeared to be a number of attempts to do that kind of thing here, and some got the message across quite clearly. But others didn’t seem to work too well—and some of the tales selected by the editor, apparently on the basis that they were counter-cultural, drifted against the culture in very good ways. One expected an entirely bad show; what turned up in fact was a very mixed bag.

S. M. Hutchens is a senior editor and longtime writer for Touchstone.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor