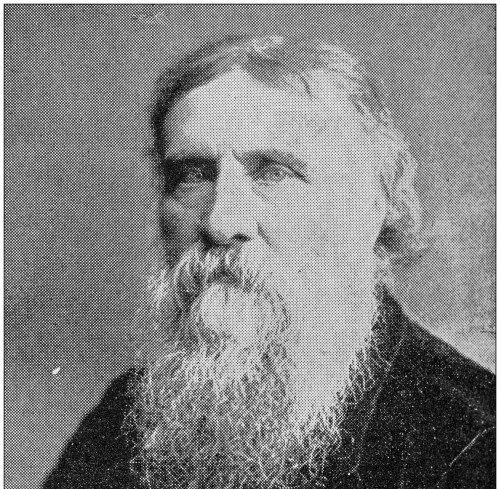

An Orthodox Appreciation of George MacDonald

Robert W. Grano on George MacDonald

One of the most frequent criticisms made against the work of George MacDonald (I’m speaking here primarily of the novels, not the fantasies) is that his characters are not realistic enough, that they are often too saintly or otherworldly. This aspect of his work is one that I find most appealing, and though I am a convert to the Orthodox Church from evangelical Protestantism, MacDonald is one of the few Protestant writers that I still read regularly.

An Orthodox Ideal

Why is MacDonald one of the few writers who has, so to speak, made the jump with me? Is there some affinity between MacDonald’s theology and that of Orthodoxy? Not really. To be honest, much in MacDonald’s theology, strictly speaking, an Orthodox would find suspect. His Christology could be described as foggy.

In some places, for example, he seems to imply that Christ was, even before the Incarnation, “man” in some sense. He also wasn’t as unwaveringly Trinitarian as an Orthodox would like, being somewhat sympathetic to the Unitarians of his day, even to the point of preaching to Unitarian congregations. He himself didn’t hold to their views, and was a convinced Trinitarian, but apparently he didn’t view Trinitarian doctrine as a non-negotiable, since he considered the Unitarians to be true Christians (even if he thought them wrong on this one issue).

MacDonald also had a tendency to come down hard on both doctrine and those who tenaciously held to it, though to be fair, his complaint seems to be chiefly with those who see themselves as doctrinally correct but don’t live according to what they teach. He was particularly tough on doctrinaire Christians of any stripe whom he perceived as not bearing any fruit. He did not suffer hypocrites gladly. His complaint was understandable, given the very strict hyper-Calvinism of his place and time (nineteenth-century Scotland), although sometimes he mistakenly seems to conclude that hypocrisy is a necessary corollary of having a strict doctrinal standard, something with which traditional Christians would disagree.

His oft-mentioned universalism is also a problem, but that is something that has appeared in the thought of both Eastern and Western theologians from time to time, and is borne, in most cases, out of a great love for people. Undoubtedly, this was true in MacDonald’s case, as it was for an Orthodox theologian such as St. Gregory of Nyssa. MacDonald’s beliefs are similar to his—theirs was not the modern notion that everyone will automatically be saved, but the idea that all will ultimately repent and be restored to God. Although Gregory’s universalism was rejected by the Church, he is Orthodox in his other views and is still considered a saint. Following the same type of reasoning, one can say that MacDonald’s doctrinal fuzziness does not make him heterodox through and through. But from these examples, one can see that it’s not his theology that creates an affinity with the East.

If it’s not the theology, then what is it? Well, in a nutshell, it’s the piety. In the East ethics and morals are considered largely in Platonic terms, with the notion of the “ideal” being central. Thus, the entire life of piety in the Eastern Church is based upon striving for the ideal or goal, which is to be like Christ. In this way, MacDonald’s portrayal of the Christ-life is very similar to that of the Orthodox Church.

An Orthodox believer who had never heard of MacDonald would, upon reading Sir Gibbie or Malcolm, feel he knew these characters, because he has come across similar ones in the lives of the saints. Gibbie is a completely selfless individual, constantly denying himself for the sake of others, and as such, seems to be more Christ-like than is humanly possible. In another way Malcolm, and Alister Macruadh in What’s Mine’s Mine, portray a different aspect of saintliness, that of those who constantly struggle to make the right choices no matter what the cost.

All pious Orthodox people read the lives of the saints, and in these and other characters in MacDonald’s novels they would find something very similar, a piety with the same flavor. The quest for these characteristics of goodness and saintliness isn’t limited to Eastern Christianity, obviously, but the East, having a Platonic mindset about such things, would feel a strong affinity towards MacDonald’s idealistic portrayal of sanctity.

Idealism & Sanctity

Robert W. Grano is a freelance writer from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He is a regular book reviewer for All Hallows: The Journal of the Ghost Story Society. He is a convert to Eastern Orthodoxy via the Assemblies of God and the Episcopal Church.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Orthodox from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor