Introduction

The late anthropologist Philip Rieff once lamented his sympathy with the modern, typically scientific, method of bracketing out and tossing aside various parts of reality in order to arrive at "illuminating" formulations that we can manage and measure beyond a shadow of doubt. The method strives to see less of something in order to say something more definitive about it. As Rieff put it:

I, too, aspire to see clearly, like a rifleman, with one eye shut; I too, aspire to think without assent. This is the ultimate violence to which the modern intellectual is committed. Since things have become as they are, I, too, share the modern desire not to be deceived.

In the Winter, 1996 issue of Touchstone, Steven Faulkner noted that many once poetically-minded men aimed to see the world with one eye shut, and later found themselves unable to recapture the true vision. Faulkner recalls the lament of Mark Twain, whose awe of the Mississippi led him to seek professional employment as a boat captain, where he learned to see the graceful curves and reflected images that had drawn him to the river in the first place for their more practical implications. In doing so, Twain said, he "lost something which could never be restored to me while I lived. All the grace, the beauty, the poetry, had gone out of the majestic river!"

Likewise, Charles Darwin bemoaned that his career of "grinding out general laws from a large collection of facts" had rendered him, by the end of his life, almost incapable of appreciating poetry and music.

One antidote, or at least a corrective, to this one-eyed way of knowing, Faulkner writes, was to cultivate a love of poetry, Scripture, and especially the Psalms.

Without it, our understanding of the world suffers a severe distortion. It is as if we have grown up in an age of one-eyed men who have heard rumors that people could once judge distances, depths, and colors by the use of two eyes, but are now reduced by this flat, prosaic information age that relies on scientific analysis as virtually our only source of knowledge. We are a century of Cyclops.

—Douglas Johnson, Executive Editor

(read more Editor's Picks)

The Century of the Cyclops by Steven Faulkner

Feature

The Century of the Cyclops

On the Loss of Poetry as Necessary Knowledge

by Steven Faulkner

Someone recently won a $75,000 poetry prize. I don’t recall the poet’s

name. The sponsors of the prize thought that big bucks would help revive interest

in poetry. The winner of the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize for $25,000, Charles Wright,

admitted that this country’s interest in poetry is in something of a free

fall, but he hoped these large prizes would arrest that fall. I doubt it will

help.

Who reads modern poetry? A reporter for National Public Radio interviewed another

poet who said that people may no longer know why “The woods—are

lovely, dark and deep,” but they do understand the money message. If someone

forks out 75 big ones for poems, poems must be valuable property.

These are cries of desperation. One comes to love poetry as a man comes to love

a woman, by first catching her eye in passing, by stumbling through a few embarrassing

conversations with her, by listening to her, attending to her, getting caught

up in the mysteries of love. If someone offered us money to take an interest

in a woman, we would know that something was drastically wrong.

Like modern art, modern poetry began to lose its audience almost a century ago.

Indecipherable and egocentric, impressionistic poetry does not catch the eye,

much less bear listening to. The old standards of Beauty, such as clarity and

coherence, have fallen to the shifting winds of subjectivism, relativism, and

skepticism. What beauty remains has been stripped from reason, severed from

its old Platonic mates, the Good and the True. Our modern poetry is in pieces.

This makes a defense of poetry difficult. But defend it we must, for poetic

knowledge is an essential kind of knowledge. Without it, our understanding of

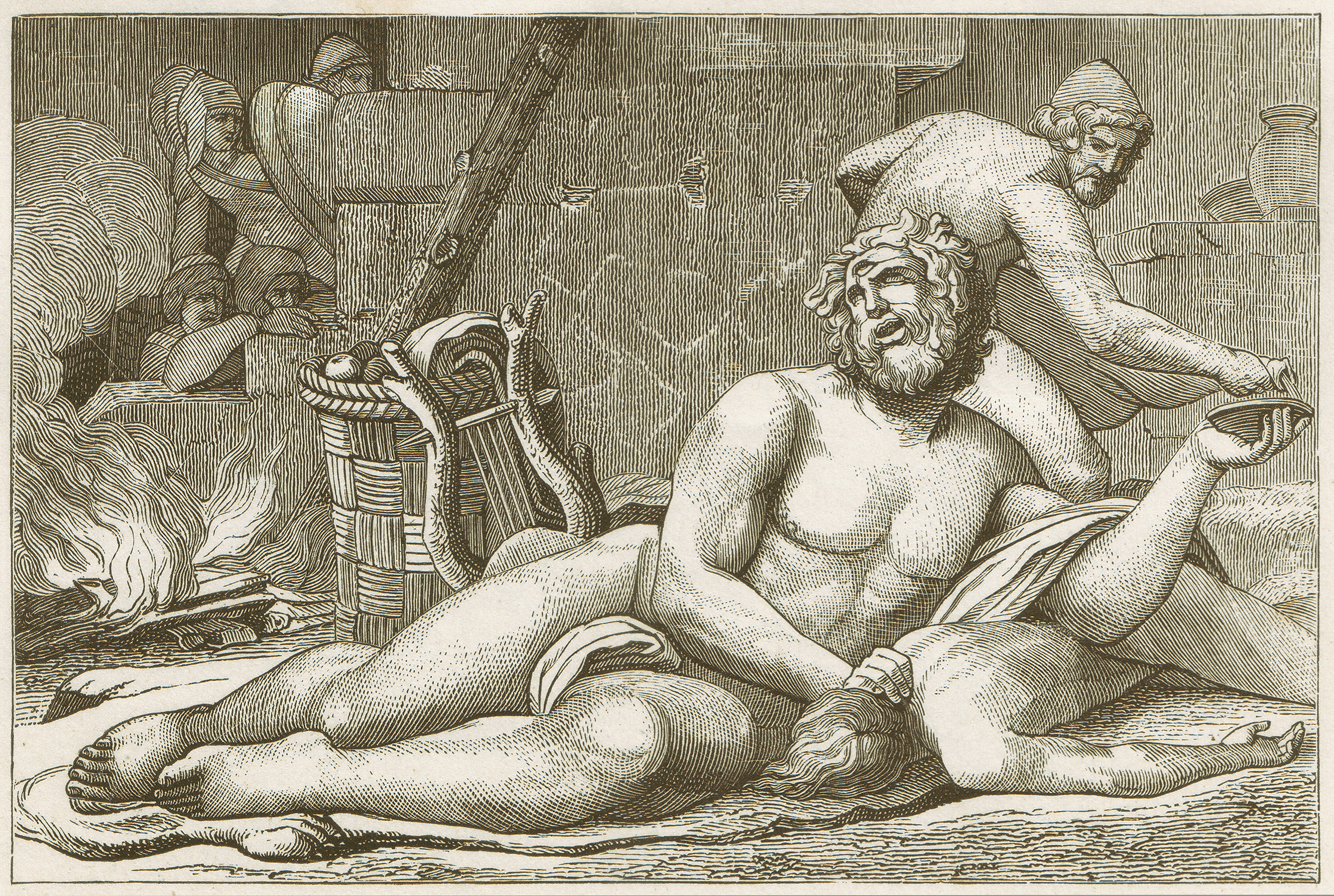

the world suffers a severe distortion. It is as if we have grown up in an age

of one-eyed men who have heard rumors that people could once judge distances,

depths, and colors by the use of two eyes, but are now reduced by this flat,

prosaic information age that relies on scientific analysis as virtually our

only source of knowledge. We are a century of Cyclops.

Poetry as a way of knowing is essential to the human being. Modern thinkers,

the heirs of Immanuel Kant, have come to depend almost entirely on discursive

reasoning, packing journals and academic books with complex analysis, deduction,

demonstration, abstraction, and argumentation. This is necessary in its place,

but it is not the only necessary knowledge.

Sir Philip Sidney, in his Defense of Poetry, written when Shakespeare

was young, said the poet “yieldeth to the powers of the mind an image

of that whereof the philosopher bestoweth but a wordish description, which doth

neither strike, pierce, nor possess the sight of the soul so much” as

poetry does.

Linear, rational discourse is the domain of philosophy and rhetoric. “The

philosopher teacheth,” said Sidney, “but he teacheth obscurely,

so as the learned only can understand him; that is he teacheth them that are

already taught. But the poet is the food for the tenderest stomachs; the poet

is indeed the right popular philosopher.” The reason for this is that

poetry appeals to the whole person, not merely to reason. Even the young and

the uneducated can appreciate it. Jacques Maritain wrote: “Poetry is the

fruit neither of the intellect alone, nor of imagination alone. Nay more, it

proceeds from the totality of man, sense, imagination, love, desire, instinct,

blood and spirit together.” Poetry can of course be highly intellectual,

demanding much from the mind, but it is always more than intellectual; it is

intuitive. It is a way of seeing and admiring the whole without taking it apart

by analysis. It is a taking into the self that which cannot be fully explained,

a way of observing with silent attention rather than active inquiry, what Wordsworth

called a “wise passivity,” or “passionate regard.”

This distinction between discursive knowledge and intuitive or poetic knowledge

is a very old idea. German philosopher Josef Pieper explains this at some length

in his book, Leisure, The Basis of Culture:

The Middle Ages drew a distinction between the understanding as ratio

and the understanding as intellectus. Ratio is the power

of discursive, logical thought, of searching and of examinations, of abstraction,

of definition and drawing conclusions. Intellectus, on the other

hand, is the name for the understanding in so far as it is the capacity of

simplex intuitus, of that simple vision to which truth offers itself like

a landscape to the eye. The faculty of mind, man’s knowledge, is both

things in one, according to antiquity and the Middle Ages, simultaneously

ratio and intellectus; and the process of knowing is the

action of the two together.

Continue Reading

Steven Faulkner teaches creative writing at Longwood University in southern Virginia. He is the author of Waterwalk: A Passage of Ghosts (2007) and Bitterroot: Echoes of Beauty and Loss (2016). Both books are memoirs of father-son journeys that followed the paths of missionary priests: Marquette (in Waterwalk) and De Smet (in Bitterroot).

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS

full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone

online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on poetry from the online archives

more from the online archives

23.2—March/April 2010

Job’s Progress

on Maturity for a Rising Generation by Peter J. Leithart

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor

Support Touchstone

00