The Demise of Biblical Preaching

Distortions of the Gospel and its Recovery

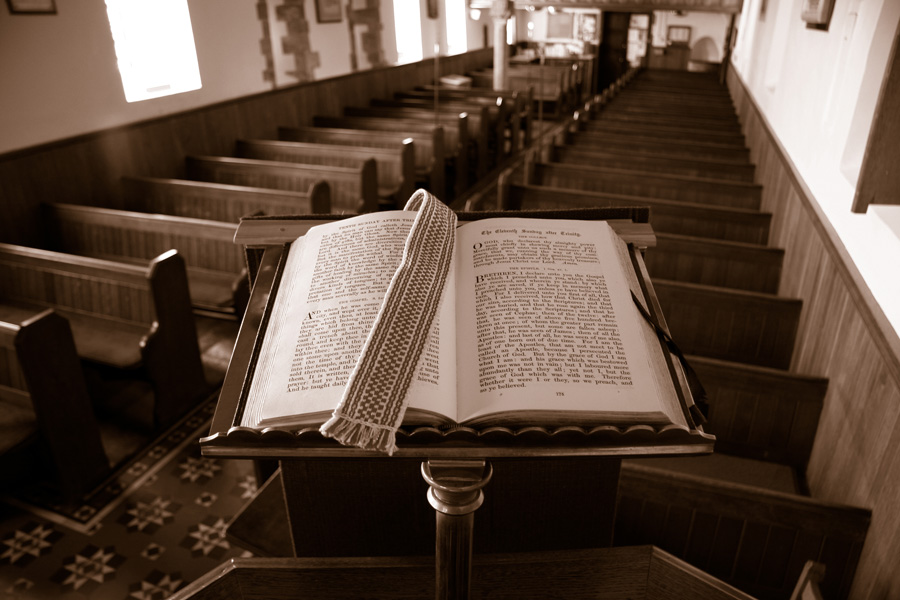

A friend of mine recently reported that a church he had previously pastored in New Zealand has removed the large, central pulpit (its only pulpit) and has substituted a screen, which is used for praise songs and choruses and also to relay graphically illustrated biblical stories and sermonic messages. What is surprising and disconcerting is that this church is related to the Church of Scotland, a branch of Christianity that has prided itself on biblical, expositional preaching. Yet what happened in this church is not unusual: throughout the Protestant world today there is an unmistakable movement from the audible to the visual, from word to image. Worship is fast becoming entertainment; the goal is no longer the glory of God and the service of his kingdom but the well-being and fulfillment of the human creature. Besides preaching, other casualties in this mega-shift include the prayer of intercession and corporate confession of sin followed by the assurance of pardon. Extended Scripture reading as a preparation for the sermon is also becoming less frequent. Solos or musical renditions by some special ensemble are increasingly taking the place of congregational singing.

The evangelical legacy that goes back to the Protestant Reformation and the renewal movements of Puritanism and Pietism sought to hold Word and sacrament together in dialectical tension, but the emphasis was on the preached Word of God. Karl Barth rightly observed that preaching virtually became a third sacrament in Reformation theology. The content of the sermon was the law and the gospel. We are to comfort the afflicted through the preaching of the gospel and afflict the comfortable through the preaching of the law (Luther). The goal of preaching was faith and obedience. The truth of divine revelation was regarded as something both objective and subjective. Its basis and content were objective, since it concerned God’s very utterance in conjunction with events in sacred history. Its communication was both objective and subjective, since this truth was given by the Spirit in the evangelical experience of an awakened heart.

Aberrations after the Reformation

The Reformation rediscovered the revitalizing power of biblical preaching, but within one generation an anthropocentric orientation began to supplant the theocentrism of the Reformers. The emphasis was no longer on justification by free grace received through faith and demonstrated in a life of obedience but rather on justification by belief in right doctrine (as in orthodoxy) or on human preparations and confirmations of justification (as in Pietism). A biblical sermon will indeed entail a call to decision, but our decision constitutes a response to the gospel rather than the content of the gospel. It is a response, moreover, induced by the outpouring of the Holy Spirit rather than an accomplishment of human free will, which would then make justification a matter of works as well as of grace.

In both conservative and liberal Protestantism that followed the Reformation, preaching often degenerated into moralism in which God’s acceptance of us was made contingent on human effort. Moralism is preaching the law without the gospel so that our hearers are told what to do in order to ensure for themselves a place in God’s kingdom rather than what God has already done for us and the whole world in Jesus Christ. Sometimes the gospel is made into a new law: it is no longer the divine promise but the divine commandment. Here Protestantism comes dangerously close to the style of preaching prevalent in the Catholic churches in which a moral homily, usually brief and to the point, takes the place of the kerygmatic proclamation.

Gnosticism is another temptation that we need to guard against if we are to remain faithful to the biblical and Reformation mandate of preaching the gospel to the whole creation. In gnosticism preaching is designed to awaken powers latent within the human psyche. The task of the preacher is to enable us to discover our own divinity or to realize untapped human possibilities. It also involves the claim to a secret knowledge of the future based on the right interpretation of biblical prophecy. The mystery of revelation is no longer the knowledge of the mighty acts of God open to all people of faith but a secret wisdom available only to those who submit themselves to the discipline of deciphering the apocalyptic code language in which a portion of the Bible is written.

Another aberration is what some in the Wesleyan-Holiness movement call easy believism and Dietrich Bonhoeffer termed cheap grace. Here we are confronted with a truncated form of orthodoxy in which the message of justification is fully affirmed, but the call to personal holiness—our response to God’s act of mercy—is muted or downplayed. In this kind of preaching we discern the gospel but not the law, whereas the whole gospel involves the preaching of the law as well as the good news of Christ’s victory over sin. A fully biblical sermon will sound the call to costly discipleship as well as celebrate the gift of costly grace—grace that cost God the life of his Son. Our mandate is to proclaim not only the message of the cross but also the command to take up our own crosses and follow Christ—not to gain salvation but to demonstrate a salvation already accomplished by God’s reconciling work in Jesus Christ.

In what I choose to call orthodoxism, teaching takes precedence over preaching and the sermon is reduced to Bible study, which can be edifying and instructive, but it is not the power of God unto salvation. The expansion of the human mind is a worthy goal, but what the sinner needs most is the regeneration of the human heart. Preaching will certainly entail a didactic as well as kerygmatic dimension, but if it remains didactic it will have little efficacy in convicting people of sin or instilling faith. Jesus was not simply a great teacher but the Savior of the world, and until we duly recognize this fact we will lack the power to make a genuine decision of faith. It is possible to preach from the Bible and yet not preach Jesus Christ or the gospel, and this is what both Protestant conservatives and liberals need to keep in mind in preparing men and women for the ministry.

Exhibitionism also lures many Protestants away from biblical and Reformation moorings. Here the aim of preaching is to make an impression on our audience rather than to give a faithful rendition of the scriptural message. Preaching becomes a performance rather than an act of obedience. The worship service is centered no longer on the Word but on the preacher—on the personality and talents that he or she brings. Preachers are expected to be masters in the art of communication more than diligent students of the Word. Their success is determined by the numbers who attend their services or give to church programs rather than by the work of the Holy Spirit in convicting people of sin and turning them to the cross in repentance and faith.

Religious enthusiasm is still another deviation from faith in the gospel. Enthusiasm, which involves constantly seeking new experiences of God, was roundly censured by both Luther and Wesley. Here the Spirit is elevated above the Word, and religious experience is prized more highly than fidelity to the gospel and the law. Sharing experiences often takes the place of expounding a biblical text. Faith to be sure is an experience as well as an act of commitment, but it is an experience that transports us beyond all experiences into communion with the living Christ. In faith we are taken out of our subjectivity into the service of the kingdom of Christ, which involves ministering to others. Luther said, “Our theology is certain because it takes us out of ourselves, out of our feelings and experiences, into the promises of God that never deceive.” There may be occasions when personal experience has a place in our preaching; yet we must never remain with the experience but always point to Christ’s experience of our sin, guilt, and death, which alone procured our salvation.

Donald G. Bloesch is Professor of Theology Emeritus at Dubuque Theological Seminary. He has written numerous books, including The Future of Evangelical Christianity, The Struggle for Prayer, Freedom for Obedience, and is currently working on a seven-volume systematic theology, Christian Foundations. He lives in Dubuque, Iowa, with his wife, Brenda.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor