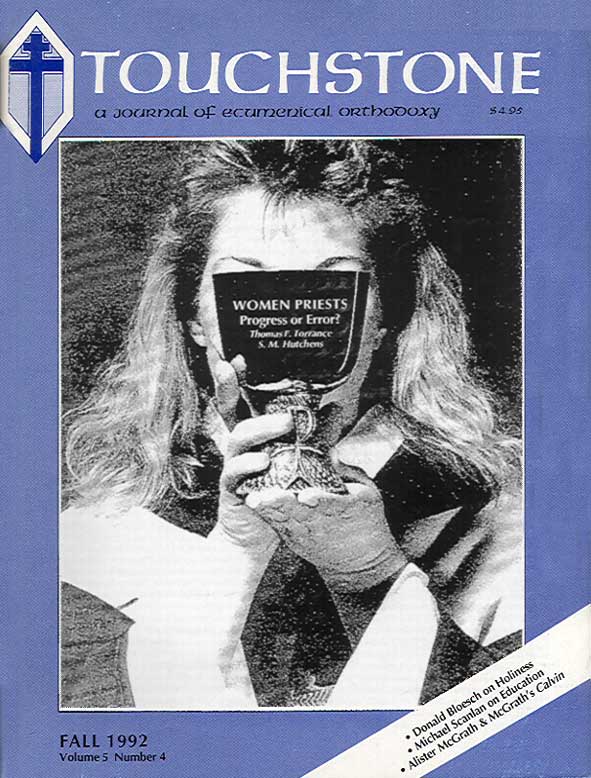

*This article does not represent the views of the Touchstone editors. It was responded to by Patrick Henry Reardon in "Women Priests: A Response to Thomas F. Torrance." See also: "On the Ordination of Women: A Correspondence Between Thomas F. Torrance and Patrick Henry Reardon."

The Ministry of Women

An Argument for the Ordination of Women

by Thomas F. Torrance

In one of the earliest of the Catacomb paintings in Rome in the Capella Greca, within a century after the death and resurrection of Christ, there is a remarkable mural depicting the breaking of bread at the celebration of the Eucharist. Seven presbyters are seated in a semi-circle behind the Holy Table, assisted by several deacons. This is known as the “Catacomb of Priscilla,” for Priscilla is seated to the right of the presiding presbyter (presumably her husband Aquila), the proestos or bishop, and is actively engaged with him in the eucharistic rite. There are two points about this painting on which I would like to comment.

The first has to do with the number seven. In the great Temple Synagogue in Jerusalem there was a Sanhedrin of 71 elders (zekenim) or presbyters together with its president or sagan. What of the smaller synagogues in the communities outside Jerusalem or in the diaspora? According to the Mishnah tractate “Sanhedrin” it was laid down that a large Jewish community might have 23 elders, presumably plus its president, making 24 in all, but if a community were 120 strong it was allowed to have its “seven” elders, which would normally be presided over by an “Archisynagogos,” just as Jairus or Crispus of whom we read in the New Testament. The “Sanhedrin” tells us that these presbyters were to be arranged “like the half or a round threshing floor so that they all might see one another.” It was thus in accordance with the regulations of Jewish law that at Alexandria, where there well over a million Jews in the first century, the local sanhedrin numbered 23 or 24, while at Rome, the Jewish community, which was differently distributed, was served by a number of smaller synagogues each with its sanhedrin of 7 elders.

Regarded in this light, that fact that the number of disciples, who with Peter formed the original Christian community in Jerusalem, was numbered about 120 (Acts 1:15), is rather significant. It helps us to understand why shortly afterwards the twelve Apostles appointed specifically “seven” disciples (presumably as “presbyters” not “deacons” as is usually held) to serve the needs of the primitive church in Jerusalem, while they gave themselves over “to prayer and the ministry of the Word” in fulfillment of their universal apostolic ministry. We also learn, however, that in due course with the growth of its membership the Jerusalem church came to have a Christian sanhedrin of seventy presbyters, probably in line with the seventy disciples sent out by Jesus on the mission of the Kingdom mentioned by St. Luke (10:1,17), but again in accordance with Jewish regulations, presided over by James, not the Apostle but the brother of our Lord.

It is not surprising, then, that in Alexandria the church had twenty-four presbyters, twelve for the city and twelve for rural districts around the city, presided over by one of their number whom they elected and consecrated as bishop. Nor is it surprising that in Rome, on the other hand, as learn from Optatus (Libri VI, CSEL, XXI, pp. 187—204), there were at least forty small churches, which evidently had their due numbers of presbyters after the pattern of the Jewish communities in Rome, but with bishops rather than rulers of the synagogue as their presidents. Incidentally this helps to explain why “monepiscopacy”—having a single bishop—was comparatively late in developing in Rome and why Clement acted as the chosen spokesman for all the churches in Rome to those beyond. It is in the Capella Greca that we are given a vivid glimpse into the assembly of one of these small congregations of believers meeting in the catacombs with their seven presbyters, Aquila and Priscilla and five others, arranged in a semi-circle “like the half of a round threshing floor.” Moreover, the Jewish as well as the Christian character of this eucharistic celebration, together with its very early date, is accentuated by a rough Hebrew inscription in the foreground.

The second point about this wall painting to which I wish to draw attention is that a woman is presented as concelebrating with men at the breaking of bread. Priscilla (or Prisca) is a presbytera officiating along with presbyteroi in the central act of worship of the church. At first sight this is rather startling in view of the statements of St. Paul: As in all the churches of the saints the women should keep silence in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak, but they should be subordinate, as even the law says. If there is anything they desire to know, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is shameful for a woman to speak in church in the context of speaking in tongues (1 Cor 14:33—35). If our Jewish friends are right, what St. Paul has in view here relates to the customary arrangement of synagogues in which women, who usually occupied seats apart from, or overlooking the main area, were forbidden to chatter or otherwise interrupt the conduct of worship. That may well be how we are to regard St. Paul’s injunctions here. Otherwise the passage is rather difficult to understand, since in an earlier chapter in the same Epistle it is assumed that women do pray and prophesy aloud in church—although it is made clear that when they do so they must have their heads covered, if only out of respect for their husbands’ authority over them (1 Cor 11:3f). Should anyone question this, however, St. Paul agrees that no such custom is found among them, or in any of the churches (1 Cor 11:16). Thus it would appear that the Apostle has no objection to women praying or prophesying in church providing that they wear a fitting cover over their heads. In the same Epistle (1 Cor 16:19) he refers to the church in the house of Aquila and Priscilla in which it is hardly likely that Priscilla kept silent!

Another passage from St. Paul’s First Letter to Timothy must also be considered: Let a woman learn in silence with all submissiveness. I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent (1 Tim 2:11—12). Here women are explicitly enjoined not to talk (lalein), but also not to teach (didaskein) in public, and perhaps also not even to teach their husbands in private! This hardly accords with the way some Jews interpret the passage just cited from First Corinthians, but whatever it means it must surely be understood in accordance with the activity of Priscilla in Ephesus, as recorded by St. Luke, when along with Aquila, she expounded the way of God more accurately to Apollos (Acts 18:26). It is hardly surprising, then, that St. Paul applies to her along with Aquila the term “fellow-worker” (synergos) which he used to refer to people associated with him in the ministry of the gospel like Timothy (Rom 16:3, 21—cf also 1 Tim 3:2; 1 Cor 3:9), or Clement (I Phil 4:3) or Mark and Luke (Philem 24).

One must also recall how St. Paul mentioned in a similar way women such as Nympha—like Priscilla she had a church in her house (Col 4:15)—or Junia, his female relative, to whom he referred as a noted apostle (Rom 16:7). Reference should be made as well to the four virgin daughters of Philip the Evangelist who were spoken of as endowed with the gift of prophecy, that is, with the gift of proclaiming the gospel as well as foretelling events. In his own list of those endowed by the ascended Lord with gifts for the ministry St. Paul put apostles first, prophets second, evangelists third, followed by pastors and teachers (Eph 4:11). That order gives some indication of the way in which the great Apostle to the Gentiles regarded the ministry of women like his kinswoman Junia and the daughters of Philip. St. Paul also speaks of women as holding the office of deaconess (1 Tim 3:11), with explicit mention of Phoebe in the church at Cenchrea (Rom 16:1), with which should be associated the order of “widows” who were not ordained but held a place of honor in the apostolic Church in fulfilling a ministry of prayer and intercession (1 Tim 5:3—16).

All this must be taken fully into account in reaching any balanced understanding of what St. Paul meant in the two passages commonly adduced by those who oppose the ordination of women in the ministry of the gospel. When we consider all that is recorded in the New Testament in this regard, it is rather difficult, to say the least, to accept the idea that there is no biblical evidence for the ministry of women in the Church. It also helps us to understand why the early Christians, who were hounded to death in the Catacombs of Rome for their fidelity to the gospel and the normative tradition of the Apostles, should have left the Church with such a definite depiction of the place of a woman presbyter at the celebration of the Lord’s Supper.

Thomas F. Torrance (1913-2007) at the time of writing was Professor Emeritus of Christian Dogmatics at the University of Edinburgh and former Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. He held doctorates in theology, science, and literature, and was associated with the Center of Theological Inquiry at Princeton.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor