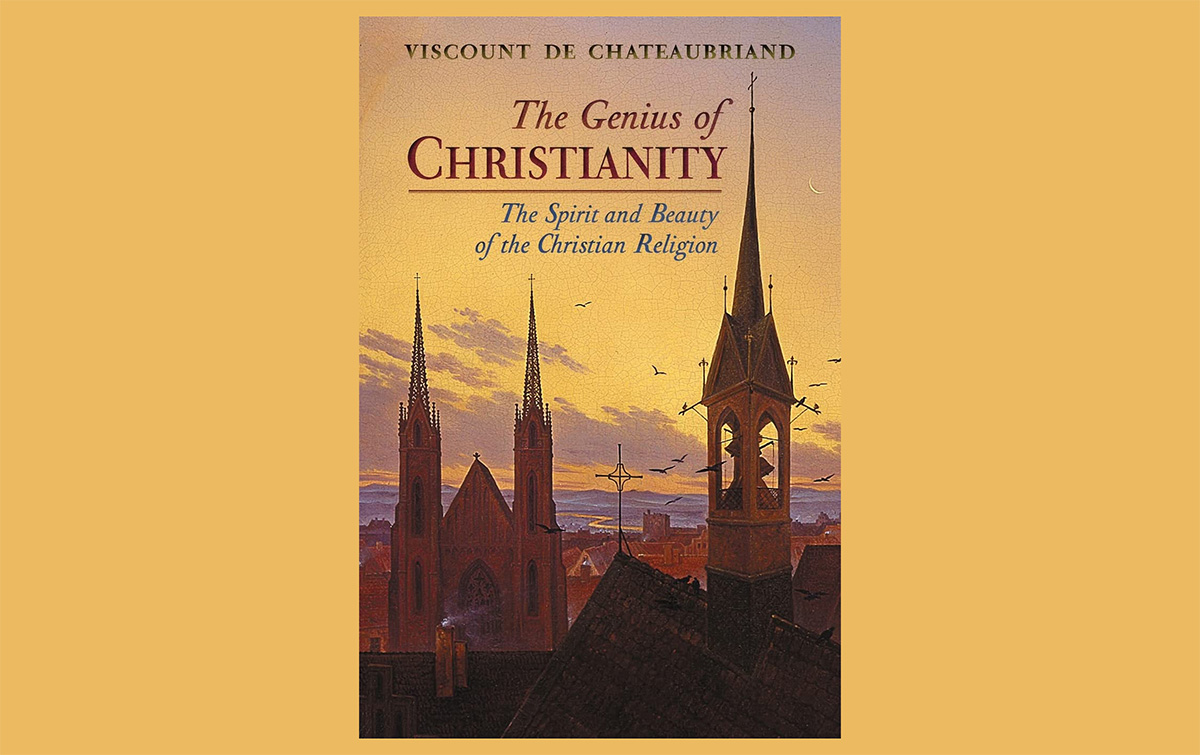

A Guidepost in Our Current Misery

Chateaubriand’s The Genius of Christianity

Hopelessness is a looming threat in our contemporary world for those of a traditionalist bent. Everywhere, it would seem, we suffer losses, and our hold on our own culture weakens. It is not too much to say that a revolution is ongoing in American society, a revolution connected to cultural and social disruption elsewhere in the Western world but with uniquely American aspects. Basic aspects of social structure are being uprooted and dismantled, and deep cultural patterns of belief and behavior are now stigmatized and steadily attacked, all of this organized by factions of political and economic elites in thrall to a morally totalitarian ideology.

A healthy sense of the enormity of what we face is not to be disdained. It is hardly unrealistic to believe that the worst is possible. But how to stave off despair? The traditionalist often does well to look to historical precedents in taking on contemporary situations, however unique they might be or appear. Revolutions have, after all, happened before, and traditionalists have found ways to stand against them.

When François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand, published The Genius of Christianity in the spring of 1802, he was newly returned to France, after a lengthy period of exile in a country that had been at war with his own country. The Treaty of Amiens had just brought an end to the chaos of the French Revolutionary Wars, though war would quickly return to Europe by the following year, once a certain Corsican general had risen to the status of emperor of France.

The young and still unknown Chateaubriand anticipated a rough reception for his book, to say the least:

What hope could I have, nameless and without any to praise me, to destroy the influence of Voltaire, who had been dominant for more than half a century . . . ? What? Diderot, d’Alembert, Duclos, Dupuis, Helvetius, Condorcet were minds without authority? What? The world ought to return to the golden Legend, renounce its acquired admiration for the masterpieces of science and reason? . . . Was it not as ridiculous as it was reckless for an obscure man to oppose a philosophical movement so irresistible that it had produced the Revolution?

Reckless and ridiculous. Perhaps. Though the years of the Terror had passed by then, the revolutionary impetus was far from blunted. The Old Regime, in all its elements—the monarchy, the established institutional order, and the cultural backbone of the Church and the faith that undergirded it—seemed forever vanquished, and the future was fraught with uncertainty and danger.

Chateaubriand had himself, for a time, doubted whether the former order could or should withstand the pressures applied by the revolutionaries. He was born into an aristocratic family that had, in his grandfather’s generation, fallen considerably in rank, but his father made a fortune at sea and subsequently purchased a castle at Combourg on the stormy Brittany coast. There, Chateaubriand was born in 1768. As he reached adulthood, he took up a military career, and the cataclysm of the French Revolution struck just as he was entering his twenties.

He was in this period a disciple of the epoch’s literary spirit of revolution, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, as were so many other bright and idealistic men in the Europe of this time, so he had some philosophical sympathies with this political revolt. But then its visceral and extreme realities began to be revealed. After the fall of the Bastille, a violent mob made its way to his family’s residence, bearing the heads of victims on pikes. Years later, Chateaubriand recounted this horrifying experience thus:

If I had had a rifle, I would have fired on these wretches as if at wolves. They screamed and hammered renewed blows on the courtyard door, to knock it down and add my head to those of their victims. . . . Those heads . . . changed my political disposition. I was horrified by these cannibal feasts, and the idea of leaving France for some faraway country was born in my mind.

Exile

Alexander T. Riley is a senior fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization and a member of the board of directors of the National Association of Scholars.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor