Eyes Fixed

Notes Towards Overcoming Our Spiritual Blindness

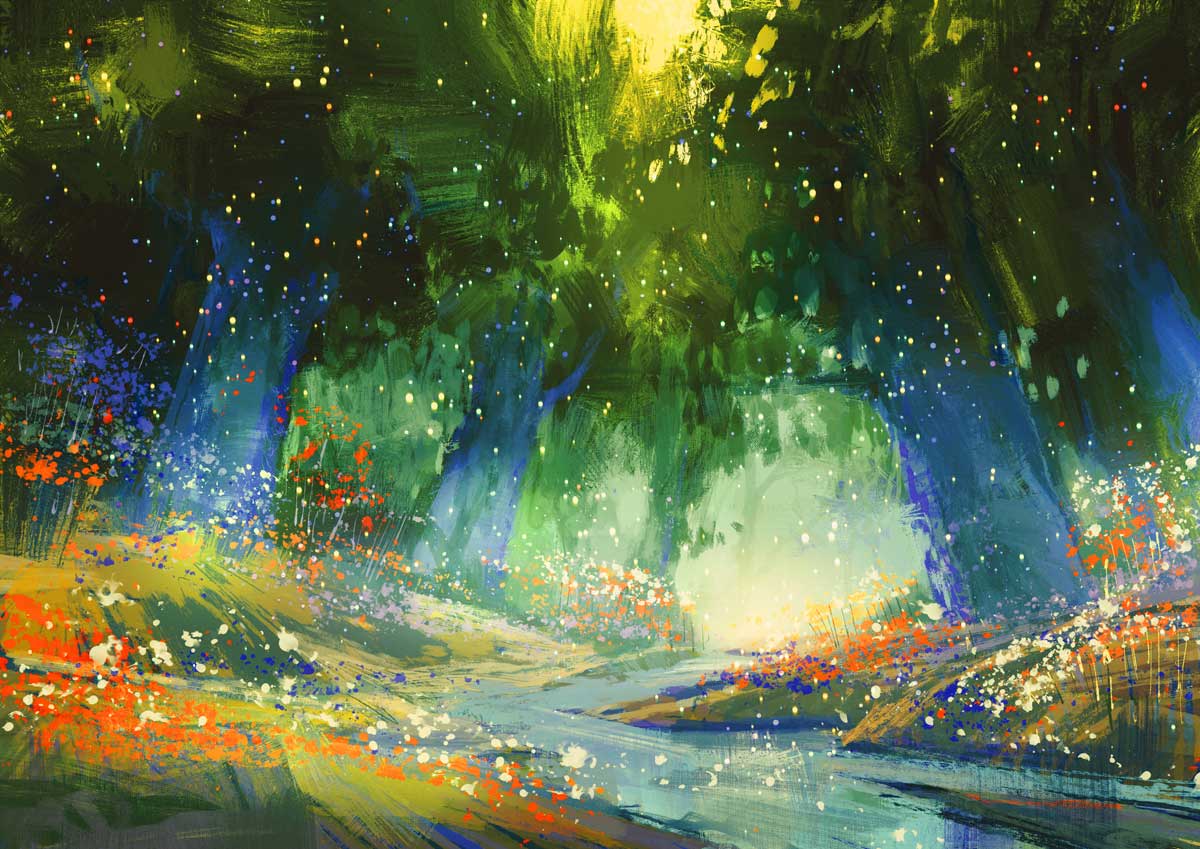

Max Weber famously called the modern condition “disenchanted.” He meant that in the modern world, people in the West have come to value science and rationality more than religion. For truly religious people, said Weber, “the world remains a great enchanted garden.” But that is no longer true, even for most Christians, who may not realize the extent to which they have been formed by the structures of disenchantment. This is why Christianity seems so powerless today, having retained the form of the faith without its power.

The only way Christianity is going to survive this new Dark Age is by Christians recovering authentic Christian enchantment—or, to use an Orthodox phrase, coming to sense that God is everywhere present and fills all things.

When was the Western world last enchanted? During the pre-modern age, which ended with the High Middle Ages. The Renaissance and the Reformation ushered in modernity, and with it, disenchantment.

According to the philosopher Charles Taylor, in pre-modern Western Christianity, there were three basic bulwarks upholding its vision of the world: First, the belief that the world and everything in it are parts of a harmonious whole ordered by God and filled with meaning. All things that exist are signs pointing to God. Second, the belief that social relations are grounded in that higher reality. And third, the belief that the world is charged with spiritual force.

Medieval people experienced God as far more present in their daily lives than we do. In their minds, God’s presence wasn’t merely a matter of belief, but of experience. As they saw it, the spiritual world and the material world interpenetrated each other. The barrier between them was thin and porous. Medieval Christians believed that God was present everywhere, and revealed himself through people, places, and things, through which his power flowed.

The entire universe was woven into God’s own Being, in ways that are difficult for modern people, even believing Christians, to grasp. Christians of the Middle Ages took Paul’s words recorded in Acts—“in him we live and move and have our being”—and in his letter to the Colossians—“He is before all things and in him all things hold -together”—in a much more literal sense than we do.

Medieval Europe was no Christian utopia. The Church was spectacularly corrupt, and the violent exercise of power—at times by the Church itself—seemed to rule the world. Yet despite the radical brokenness of their world, medievals carried within their imaginations a powerful vision of integration.

In the medieval consensus, men construed reality in a way that empowered them to harmonize everything conceptually and to find meaning amid the chaos. The medieval conception of reality is an old idea, one that predates Christianity. In his final book, The Discarded Image, C. S. Lewis, a professional medievalist, said that for Christians of those days, regarding the cosmos was like “looking at a great building”—perhaps one like Chartres cathedral—“overwhelming in its greatness but satisfying in its harmony.”

Metaphysical Disconnect

Now, the fateful step away from the medieval model came in the fourteenth century, in a philosophical dispute between Catholic academics. The medieval model collapsed and was replaced by a model based on two concepts: “nominalism” and “voluntarism.” The upshot of this was that people began to regard God as somehow separate from Creation. Creation only meant something because the God who existed wholly separate from it looked at it and said it was meaningful.

Rod Dreher is a contributing editor to Touchstone. He is a writer and blogger and the author of several books, including The Benedict Option (2017) and Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents (2020).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on imagination from the online archives

11.5—September/October 1998

Speaking the Truths Only the Imagination May Grasp

An Essay on Myth & 'Real Life' by Stratford Caldecott

more from the online archives

33.1—January/February 2020

Do You Know Your Child’s Doctor?

The Politicization of Pediatrics in America by Alexander F. C. Webster

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor