View

War & Peace After Jesus

Andrew Latham on Pacifism Today & in the Early Church

Following a gathering last April in Rome sponsored by Pax Christi International, the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, and a number of other international Catholic organizations, educators and activists from all over the world issued a statement calling, among other things, for the Catholic Church to "no longer use or teach 'just war theory.'" In its place, they proposed, the church should commit itself to "a Just Peace approach based on Gospel nonviolence." Specifically, the conference participants called for Pope Francis to issue an encyclical on nonviolence, integrate gospel nonviolence into the life and work of the church, promote nonviolent practices and strategies, and initiate a global conversation on nonviolence.

Although the concluding conference statement does not mention it explicitly, one of the main arguments behind this call to abandon the Catholic just war tradition and embrace in its place the centrality of gospel nonviolence is the claim that, before its "Constantinian fall," the church uniformly preached and practiced an ethic of gospel nonviolence. Indeed, in the run-up to the conference, Terrence Rynne, professor of peace studies at Marquette University and one of the conference participants, published an essay in the online version of the National Catholic Reporter arguing in favor of abandoning Catholic just war theory on several grounds. Among them was the assertion that the early church—that is, the church as it existed prior to the Constantinian settlement—proved that an absolute commitment to nonviolence is not only desirable (in the sense that it reflects the true teachings of Christ), but practical as well. As he put it, for "the first three-plus centuries of the early Church, Christians followed the nonviolent, positive way taught by Jesus. They demonstrated that it was not dreamy idealism, but politically effective."

According to Professor Rynne, the witness of the early Christians through nonviolent resistance and martyrdom was so compelling that it ultimately resulted in the conversion of the entire Roman Empire to the Christian faith. He concluded from this that nonviolence and "positive peace" should replace Catholic just war theory as basic church teaching with respect to war and peace.

Looking at the Evidence

What are we to make of this claim? Or, to put it slightly differently, what are we to make of the assertion that during the first three-plus centuries of the Church, Christians embraced nonviolence in both theory and practice?

First, I would argue that such a claim is simply contradicted by the available empirical evidence. Christians, it seems, did not uniformly follow "the nonviolent, positive way taught by Jesus." Indeed, as scholars such as Edward A. Ryan and James Turner Johnson have convincingly demonstrated, the historical record strongly suggests that Christians did in fact serve in the Roman army.

To be sure, although we have no source material to prove it, it is probable that not many Christians served with the legions prior to a.d. 170. Evidence does clearly reveal, however, that after about 170 the Christian presence in the Roman army grew considerably. And while church fathers like Tertullian counseled ardently against Christian service in the legions, they were nevertheless forced to concede that Christians did, in fact, serve in them. Indeed, it is likely that the fathers' increasingly vehement condemnation of Christian service was at least partly a function of the growing numbers of Christian soldiers—due both to Christians enlisting in the Roman army and to Roman soldiers converting to Christianity. In any case, in light of the work of Ryan, Johnson, and others in recent decades, few would now maintain that Christians uniformly avoided military service or that they unvaryingly "followed the nonviolent, positive way taught by Jesus."

Second, it is simply not the case that the fathers of the early Church were pacifists—at least if we define pacifism as a principled belief that any violence, including that of war, is unjustifiable under any circumstances. To be sure, there is little doubt that the fathers opposed Christian service in the Roman army. Whether they did so on the grounds of a deep-seated aversion to the idolatrous practices of the pagan Roman army (most famously argued by John Helgeland), a scripturally derived antipathy to bloodshed (highlighted by Alan Krieder), or respect for the dominical command to love one's enemies and pray for one's persecutors (an argument recently advanced by George Kalantzis), the scholarly consensus is that the early church fathers viewed service in Rome's legions as incompatible with the moral strictures of Christianity.

Tertullian & Origen

Nowhere in the writings of the fathers, however, do we find an aversion to the use of military force as such. Indeed, Tertullian (c. 155–240), ultimately one of the staunchest opponents of Christian military service, actually began his public life celebrating such service. In the Apology (a.d. 197), for example, he emphasizes and applauds the responsible participation of Christians in the public life of Rome—including military service. As he put it in response to claims that Christians were indifferent or inimical to the common good of the empire: "We sail with you and fight alongside you and serve in your army." He also favorably cites the Legio Fulminata, the famed and largely Christian "Thundering Legion" that fought heroically under Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Finally, it is in the Apology that Tertullian first recognizes the necessity of having "brave armies" capable of defending the empire, a theme that would persist in his later writings even as he waxed increasingly hostile to Christian service in the Roman army.

Andrew Latham is a Professor of Political Science at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. He is the author of Theorizing Medieval Geopolitics: War and World Order in the Age of the Crusades (2011), The Holy Lance (2015), a novel dealing with the Third Crusade, and Medieval Sovereignty (2022).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

8.4—Fall 1995

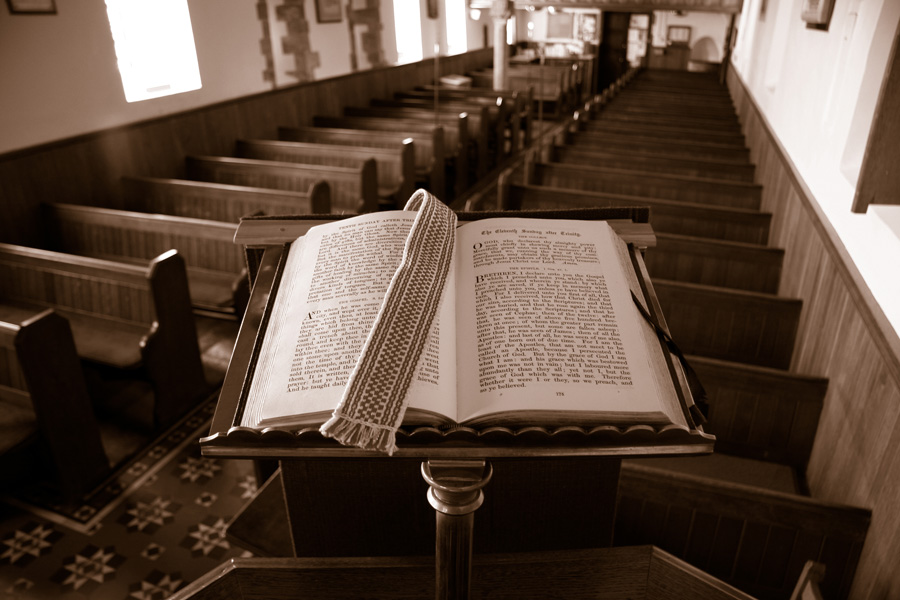

The Demise of Biblical Preaching

Distortions of the Gospel and its Recovery by Donald G. Bloesch

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor