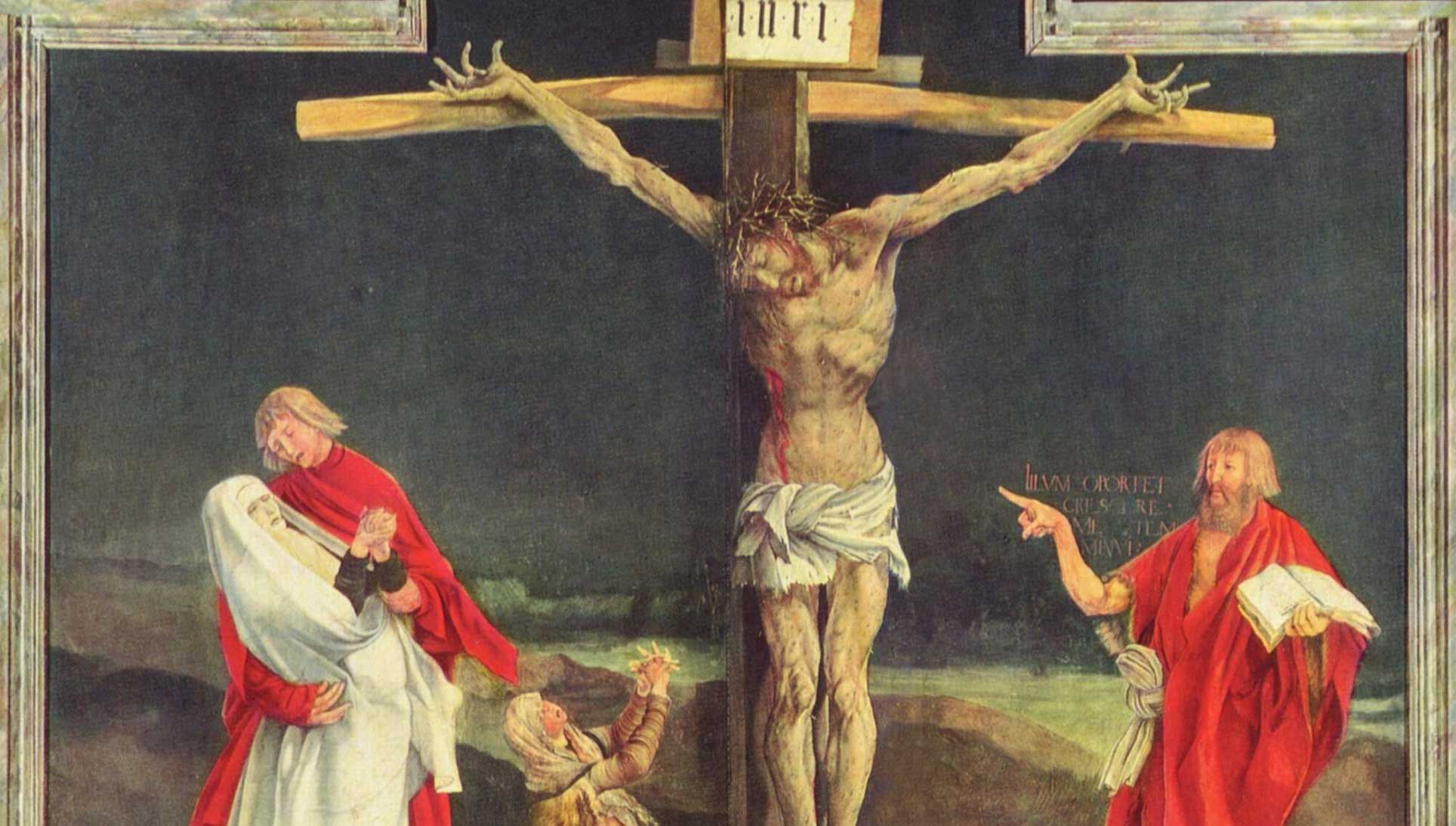

From Modernity To Auschwitz

The Secular & Anti-Christian Origins of the Holocaust

by Joe Keysor

In his lengthy book The Holocaust in Historical Context, Steven Katz of Boston University links biblical Christianity to the crimes of the Nazis. While Katz recognizes the obvious fact that the Nazis were not Christians—that they were, in fact, hostile to Christianity—he still claims that centuries of Christian-inspired hatred of Jews, derived from the Bible, contributed indirectly but significantly to the murder of six million Jews. Christianity is thus blamed for creating a reservoir of hate that the non-Christian Hitler skillfully exploited.

Anti-Semitism is so far removed from all fundamental biblical teaching that we must reject any attempt to use it to impugn the gospel of Christ. While many such accusations arise from hostility to Christianity and a desire to disparage it at every opportunity, there may be a deeper and a subtler motive at work. Zygmunt Bauman describes this motive in his thoughtful book Modernity and the Holocaust as a desire to avoid the fact that the Holocaust was a product of modernism—a troubling thought that calls into question the entire modernist project.

If the secularists can, to a significant extent, blame the brutalities of Nazism on religion, then they do not have to confront Bauman’s claim that “the Holocaust was a characteristically modern phenomenon that cannot be understood out of the context of cultural tendencies and technical achievements of modernity.” Pointing at religion thus becomes (as he says) merely one way “to belittle, misjudge, or shrug off the significance of the Holocaust”—and the dream of modernity as progress guided by independent human reason remains untarnished.

If, however, we are not wedded (or chained?) to the modernist paradigm, if we do not feel obligated to defend our beliefs in the goodness of human nature, in the power of reason to order and improve society, and in the benefits of freedom from divine law—if we do not see Hitler’s crimes as a religiously influenced deviation from an otherwise sound modern secular outlook—then we can consider the horrors of National Socialism in a different light.

A New Anti-Semitism

The eighteenth century saw the emergence of a powerful intellectual movement that denied the need for divine revelation and boasted of the power of unaided human reason to create a better world. Optimistically named “the Enlightenment,” this movement originated primarily in France, but was eagerly received in Germany as well. It was this “Enlightenment” that introduced a new and different way of looking at the Jews—one based on human reason—which became integral to German anti-Semitism in the following generations.

The secular thinkers of the German “Enlightenment” (Aufklaerung), of whom we may take Immanuel Kant as a prime example, were not concerned about God’s wrath on the Jews for their rejection of Christ. Such a concept of God was alien to them. Their concerns were very different, and their increasingly strident objections to Jews were different. To begin with, it was the concept of Judaism itself, as secular thinkers found it in the Torah, that offended them. A God of one nation only, who imposed all sorts of stifling rules and regulations, who rewarded obedience with material blessings and visited severe punishments for various sins, was anathema to those who, like Kant, felt that human civilization had outgrown the need for such divine tutelage. Moreover, verses such as Genesis 28:20–21 were used to show that the main concern of the Jews was selfish advantage and material benefit, not a disinterested love of truth for its own sake.

Related to the charge of selfishness and materialism was Kant’s accusation that the Jews had no real emphasis on the afterlife. Missing clear references in the Jewish Scriptures to an afterlife (such as Isaiah 51:6 or Daniel 12:2–3, to name only two), Kant accused the Jews of being concerned with this life only. As he wrote in Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone, “since no religion can be conceived of which involves no belief in a future life, Judaism, which, when taken in its purity, is seen to lack this belief, is not a religious faith at all.” Thus, when Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf, “he [the Jew] lacks idealism in any form, and hence belief in a hereafter is absolutely foreign to him,” he was not expressing ideas derived from the older, religious anti-Semitism, but from a newer tradition (by Hitler’s time, such arguments were widely diffused throughout the culture).

Joe Keysor has been teaching English overseas since 1995—in China, Oman, and now at Prince Sultan University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. He has written two books on the subject of Hitler and Christianity (both published by Athanatos Christian Ministries): A Horror of Great Darkness: Hitler and the Third Reich in the Light of Biblical Teaching (2014) and Hitler, the Holocaust and the Bible: A Scriptural Analysis of Anti-Semitism, National Socialism, and the Churches in Nazi Germany (2010).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

15.6—July/August 2002

Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World

The Shape of Divine Providence & Human History by James Hitchcock

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor