Features

God’s English

The Making & Endurance of the King James Bible, 1611–2011

The King James Version of the Bible (KJV) is fast becoming one of the great unread books of Western civilization—remembered and admired but not used. True, there is still a small band of believers in the fundamentalist tradition whose loyalty to the KJV remains uncompromised. But the vast majority of Christians in the English-speaking world think of the King James Bible as a hindrance rather than a help: an interesting document but, in the twenty-first century, pointlessly difficult to understand; an artifact prized by one’s grandparents because it reminded them of another time.

It’s the sad but inevitable end to the greatest of all biblical translations—sad because the translators’ goal was to make the Scriptures more, not less, accessible: a goal they achieved on a worldwide scale. Miles Smith’s preface to the first edition explains that goal beautifully.

Translation it is that openeth the window, to let in the light; that breaketh the shell, that we may eat the kernel; that putteth aside the curtain, that we may look into the most Holy place; that removeth the cover of the well, that we may come by the water, even as Jacob rolled away the stone from the mouth of the well, by which means the flocks of Laban were watered. Indeed without translation into the vulgar tongue, the unlearned are but like children at Jacob’s well (which was deep) without a bucket or something to draw with; or as that person mentioned by Isaiah, to whom when a sealed book was delivered, with this motion, Read this, I pray thee, he was fain to make this answer, I cannot, for it is sealed.

For well over three centuries in Britain and North America, the King James Bible was the Bible. Its language permeates our literature. In twenty-first-century Britain, where biblical illiteracy is almost total, phrases from the King James Bible still echo across the cultural landscape—a fact attributable to the nation’s Christian past, but also to the biblical translation that defined that past.

Even so, the Authorized Version, as it used to be called, is now thought of chiefly as an historical novelty. Young people raised in Christian homes today are hardly aware of its existence. Accessible translations, some of them very good, proliferate. You can hardly blame a modern congregation, one with no historical or emotional ties to the King James Version, for avoiding it—all the thee’s and thou’s and begat’s and whithersoever’s can sound bizarre to younger Christians. Yet somehow it seems tragic that a young Christian in an English-speaking country should enter adulthood with no experience of the KJV’s language.

As the King James Bible turns 400, it’s worth reflecting on what we’ve lost.

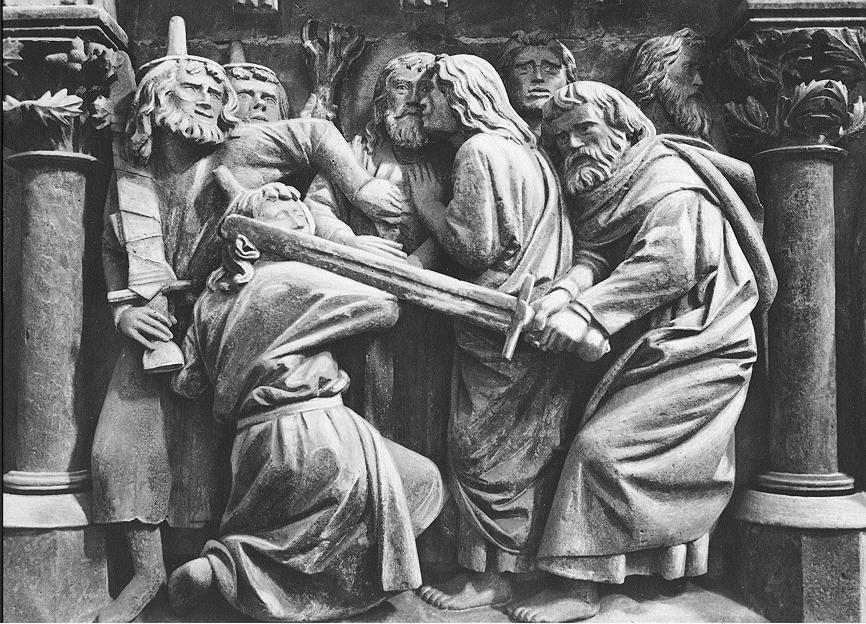

James & Geneva

It is impossible to appreciate the triumph of scholarship that was the King James Bible without first appreciating its provenance. In 1603, when James VI of Scotland ascended the English throne upon the death of Elizabeth I, the idea that the Scriptures ought to be translated at all was still a recent one. As late as 1513, John Colet, Dean of St. Paul’s, had been suspended from his preaching duties for having translated the Lord’s Prayer into English. But by the end of the sixteenth century, there were several English Bibles in circulation, legal and illegal. The problem was that the idea of biblical translation was still new enough to be a deadly serious one, and none of the available translations appealed across theological lines.

So for Britain’s political and ecclesiastical leaders, the question was no longer whether the nation would have an English translation of the Bible, but which one it would have. And in 1603 there was no obvious answer. The Bible then given royal sanction, the Bishops’ Bible of 1568, was a mostly competent but uneven translation (now remembered chiefly, though unfairly, for its rendering of Ecclesiastes 11:1—instead of “Cast thy bread upon the waters,” it read, “Lay thy bread upon wet faces”). The most accurate translation was the Geneva Bible, a superb work of scholarship produced by a group of English exiles in Geneva during the reign of Mary Tudor (whose death in 1558 had made Elizabeth I Queen).

Barton Swaim works as a speechwriter and is the author of Scottish Men of Letters and the New Public Sphere (Bucknell, 2009). He is a member of First Presbyterian Church in Columbia, South Carolina, a church of the Associate Reformed Synod.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on bible from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor